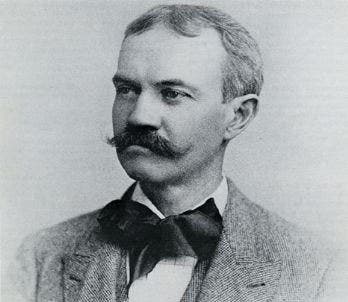

Scientist of the Day - Edward Kemeys

Edward Kemeys, an American animal sculptor, died May 11, 1907. Born in 1843 in Georgia, he moved to New York, where he worked as an iron worker; he served with the North in the Civil War. After the War, working on the continued construction of Central Park, he encountered, it is said, a man sculpting a wolf's head, and suddenly Kemeys’ life calling was clear to him. He essentially taught himself to be an animalier, the word coined by the French to describe an animal sculptor, and like a proper student of the genre, he went to Paris, the animalier’s mecca, and supposedly he even managed to meet Antoine-Louis Barye, animalier supreme in France, although Barye would have been almost 80 years old. But Kemeys decided sculpting animals that occupied the Paris Menagerie, as most of the animaliers did, was an unfulfilling experience, compared to modeling wild animals on the American frontier. He came back to the States and made numerous trips out west over the course of his career; most of his famous sculptures depict bison, bears, wolves, and the like.

One of Kemey's first commissioned sculptures was a bronze depicting two arctic wolves (third image, below). It was cast in 1872 for the Philadelphia Zoo, put in place the next year for the zoo’s opening in 1874, and although it has been relocated several times, it is still there. At least it was when this photo was taken.

In 1885, Kemeys did a jaguar on the hunt, which is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City; it reflects Kemeys’ skill in depicting the "all-senses-on-alert" appearance of an animal about to spring (first image). This is a small bronze, only about 20 inches long. If you go to the Met’s webpage for this sculpture and enlarge the image, you can see, next to Kemeys’ signature, a small wolf’s head, which he used as a maker’s mark. Apparently that initial encounter with the man carving a wolf’s head made quite an impression on young Kemeys.

But there is no doubt that Kemeys’ most famous bronzes are the pair of lions that he sculpted for the opening of the Art Institute of Chicago building on Michigan Ave. (fourth image, above). The neoclassical structure was actually built for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, but it was already in the planning that when the Exposition moved out, the Art Institute would move in, and the board commissioned Kemeys to provide them with suitable heroic beasts to flank the wide entrance. They were unveiled on May 10, 1894, and they have charmed visitors ever since, although there is nothing charming about them. Each animal is about 4000 pounds of bronze, and in addition to facing in opposite directions, they have slightly different poses, the one on the south (fifth image, just above; on the right in the fourth image) being defiant, while the northern lion, open mouthed, is “on the prowl.”

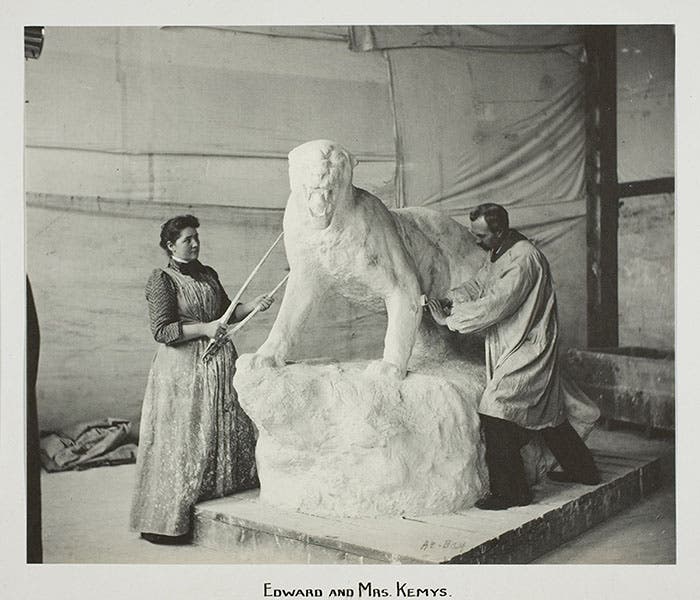

The Art Institute has a photo in their archives that depicts Kemeys and his wife Laura at work in their studio. The caption says they were preparing a model for the 1893 Exposition, but it is clearly not a lion they are working on, but a sleeker cat (sixth image, above). It appears to be a heroic-size version of the bronze jaguar in the Met. I wonder where that ended up?

Reproductions of Edward Kemeys Art Institute lions, by Alva Studios, author’s collection, 1980 (photo by the author)

If you would like your own Kemeys work of art, you can watch the auction houses; a wonderful terracotta basset hound sold at Christie’s for $27,500 in 2009. Or, if your budget is more like mine, you can keep an eye on eBay. In 1980, Alva Studio offered a set of the two Art Institute lions in “Alvastone,” a surprisingly convincing substitute for bronze. Probably intended as bookends, they show up on the market every now and then. I know they showed up once, because I was a successful bidder, and for this occasion, I posed them out in the sun, in my backyard, where they seem quite content, and still uninterested in one another.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.