Scientist of the Day - Edward Arthur Milne

Edward Arthur Milne (nearly always referred to as E. A. Milne), a British astrophysicist and cosmologist, was born Feb. 14, 1896, at Hull in Yorkshire. He attended Hymers College in Hull, worked on anti-aircraft ballistic problems during World War I, and then studied at Trinity College, Cambridge. He became Professor of Mathematics at Oxford and a Fellow of Wadham College there in 1928.

Milne was one of the most brilliant students of stellar structure in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but he clashed with Arthur Eddington at Cambridge. Eddington had formulated the first theory of stellar interiors in the mid-1920s, and, amazingly, was able to relate such things as luminosity to mass without actually understanding how stars produce energy (no one would know that until 1938 and the work of Hans Bethe). Milne criticized Eddington on this and several other points, and Milne was furiously attacked in return by Eddington – attacked so viciously that Milne was driven right out of stellar theory into cosmology.

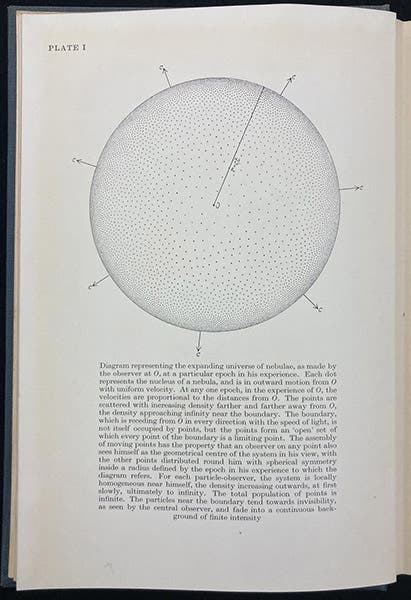

Cosmology in the early 1930s was dominated by the general relativity of Albert Einstein, which explained gravitation as a curvature of space-time, with a considerable helping of Georges Lemaître thrown in. Milne had little use for concepts that made no observational predictions, such as space-time, and curved space, and he rejected them. He developed a gravitational theory that utilized special relativity but dispensed with general relativity. He called it kinematic relativity, where kinematic is an old medieval word that refers to the study of motion without consideration of forces. Kinematic relativity worked reasonably well, but Milne’s rejection of general relativity drew criticism from just about everyone except philosophers of science, who liked his epistemological stance, known as hypothetico-deductive rationalism. Milne’s cosmology was set out in two books: Relativity, Gravitation and World-Structure (1935), followed thirteen years later by Kinematic Relativity; A Sequel to Relativity, Gravitation and World Structure (1948). We have both of these works in our collections (second and fourth images). One of Milne’s hypotheses, the cosmological principle, which maintains that the universe should look the same to all observers (third image), was picked up by Hermann Bondi, given a time dimension, renamed the perfect cosmological principle, and adopted as a cornerstone of the Steady State cosmological theory postulated by Bondi, Fred Hoyle, and Thomas Gold in 1948.

Philosophy of science does not often influence working scientists, so the Milne-Eddington contretemps is an exception of interest. There is a fine explication of the complex cosmological debates of the 1930s, written by George Gale, in the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which you can find at this link, and which you can easily understand, even if you are untrained in the philosophy of science.

Milne’s last years were not pleasant ones, for reasons that had nothing to do with cosmology. His first wife had committed suicide in 1938, and his second wife did the same in 1945. What a terrible double tragedy to have to deal with! On top of that, Milne suffered a recurrence of encephalitis, which he had first contracted during the epidemic of the 1920s when he was 25, and, although he recovered, the “sleepy sickness” was apparently merely sleeping, and came back with a vengeance in the late 1940s. He died of it, in 1950, at the age of 52.

Milne was a lifelong best friend of Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, the Indian mathematician who came to Cambridge in the 1920s and studied white dwarf stars, and also drew forth denunciation from Eddington. Chandra, as he was called, was subjected to considerable racial discrimination in England, but not from Milne. He said of Milne: “He was the only man in England who befriended me unconditionally.”

In 2015, the University of Hull established the E. A. Milne Centre for Astrophysics in Milne’s honor. There is a blue plaque commemorating Milne at Hymers College in Hull (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.