Scientist of the Day - Edouard Devilliers du Terrage

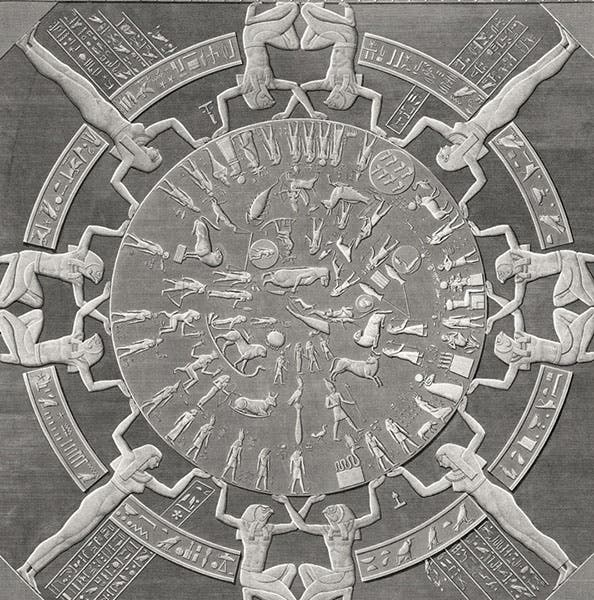

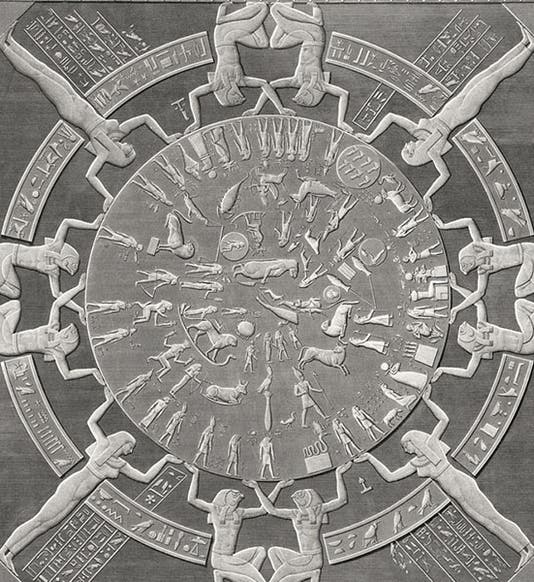

The zodiac of Dendera, detail of an engraving, after a drawing by Edouard Devilliers du Terrage and Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois, Description de l’Égypt, Antiquités, plate vol. 4, 1809-28 (Linda Hall Library)

Edouard Devilliers du Terrage, a French topographic engineer, was born Apr. 26, 1780. He entered the new École Polytechnique, founded in 1794 to train engineers, and before he even graduated, he was tapped by senior scientists to join Napoleon on his scientific expedition to Egypt in 1798. All of 18 years old, Devilliers rode with a fellow student in a coach from Paris to Lyons with Claude-Louis Berthollet, Joseph Fourier, and Pierre Costaz, three of the most distinguished scientists in all of France, which must have been unnerving for young Edouard and his friend. But then, Berthollet and Fourier were the ones who chose them as expedition members.

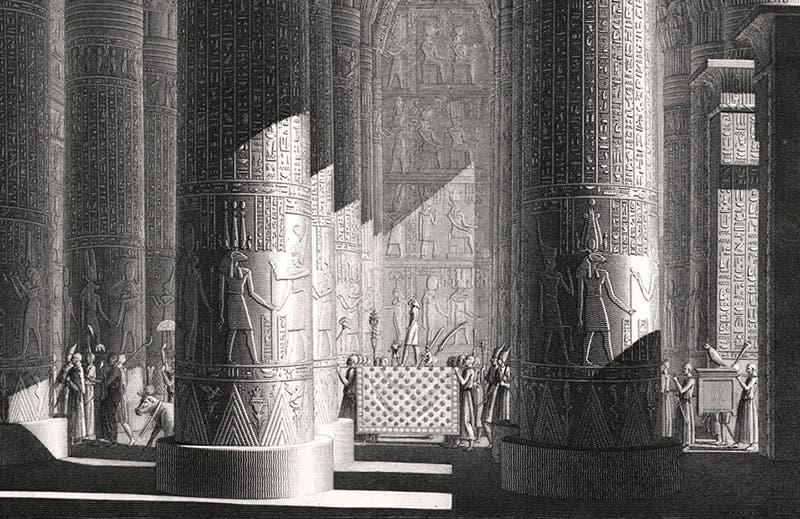

Devilliers was one of about 150 scholars chosen to accompany Napoleon to Egypt. They landed at Alexandria on July 1, 1798 and bided their time in Rosetta while Napoleon and his army conquered Cairo. Devilliers then proceeded to Cairo, where in, October of 1798, he was formally examined by Gaspard Monge and awarded his degree. His big moment came in March of 1799, when Devilliers accompanied a military expedition to upper Egypt, and there teamed up with another slightly older engineer, Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois, to make a topographic survey of the country. But when they stumbled across the many ancient sites that lay along the Nile, they got sidetracked, and started sketching antiquities. Their first big find came at Dendera, which they reached on May 25, 1799. There, on the roof of the Temple of Hathor, they found the soon-to-be famous Zodiac of Dendera, which they carefully drew and would later have engraved (first image). It had actually been discovered some months earlier by Dominique-Vivant Denon, but Denon had had no time to make anything but a hurried sketch. The Devilliers/Jollois drawing is much more precise and accurate. It would later be engraved in one of the Antiquités volumes of the Description de l'Égypte, a set of which we have in the Library. We displayed many of the 26 volumes in our 2006 exhibition, Napoleon and the Scientific Expedition to Egypt.

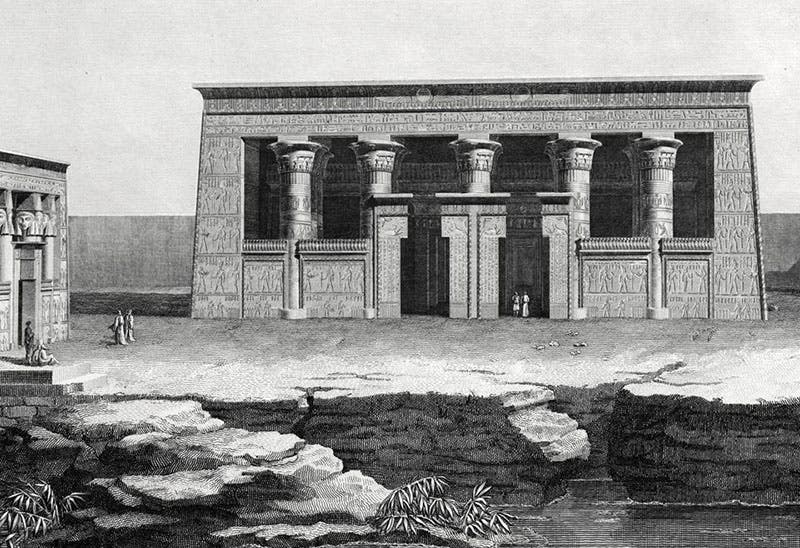

Devilliers and Jollois and their fellow engineers went on to discover, survey, and draw many of the famous ancient sites along the Nile, such as those at Luxor, Karnak, Esna, and Philae. Interestingly, the chief engineer, Pierre-Simon Girard, was very much opposed to his engineers wasting their time on ruins when they should be doing military mapping, and Devilliers and Jolois had to sneak in their antiquities studies on the sly. Fortunately for the young artists, Girard could only be one place at a time, and when he was away, their pencils flew.

Each of the topographic engineers had a different style, and their own preferences in subjects to draw. We have previously written posts on Charles-Louis Balzac, who liked to draw ruins populated with locals and soldiers, and Andre Dutertre, who drew some sweeping landscapes, but preferred closer views of individual relics. Devilliers and Jollois liked to do visual reconstructions. They would gaze at a ruin, and map it, and try to imagine what it looked like in ancient times. Then they would restore it to life with their pens and pencils. Usually, they would people their restored temples with ancient Egyptian worshippers in imaginary pharaonic garb. We show here details of the reconstructions they did of the temple interiors at Esna (third image) and Dendera (sixth image), and of the facade of the temple at Kom Ombo (fourth image). We show details because the plates are so large that you lose all detail if you try to reproduce the entire engraving.

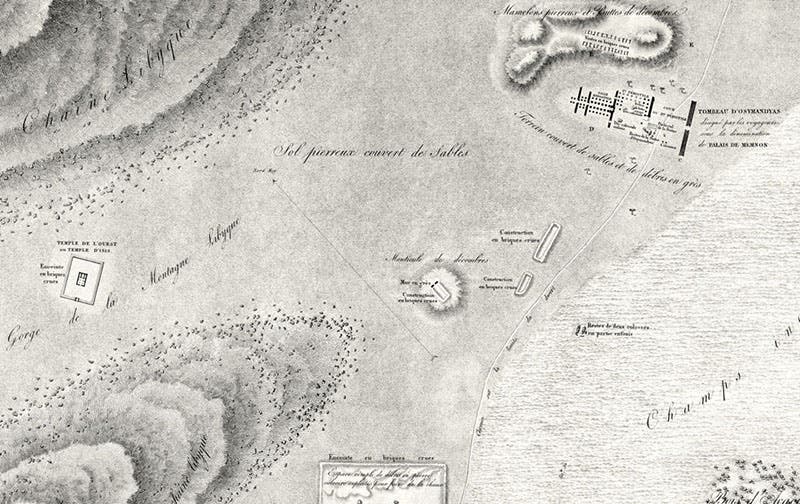

Jollois and Devilliers, being good topographic engineers, were also expert at mapping, executing groundplans of Dendera, Philae, and many other sites they visited. We show here a detail from their map of the Memnomium, the region west of Thebes that we now know as the Ramesseum, a temple for Rameses II, but which at the time was thought to be the tomb of Ozymandias (seventh image, below). The semi-circular area at bottom right is floodplain, and just into that area, you can barely see two tiny labelled objects. These were called the Colossi of Memnon, two huge seated statues out where they shouldn’t be in the floodplain. Denon sketched them on his own visit and later published his view; we displayed it in our 2006 exhibition, and you can see it there in the published catalog. You can also see there his sketch of the Temple of Hathor at Dendera. It was on the roof of this temple than Denon, and later Devilliers and Jollois, found and drew the Zodiac of Dendera.

Groundplan of the region around the Memnonium on the plains west of Thebes; the temple at top right is labelled the “Tomb of Ozymandias;” the two seated “Colossi of Memnon” are barely visible on the floodplain south of the temple; detail of an engraving, after a map by Edouard Devilliers du Terrage, Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois, and two others, Description de l’Égypte, Antiquités, plate vol. 2, 1809-28 (Linda Hall Library)

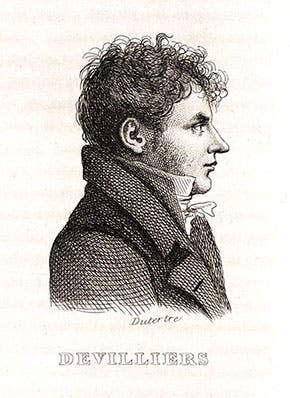

When he wasn’t drawing ruins, Andre Dutertre like to do portraits, and he sketched nearly all of the 150 savants on Napoleon’s expedition during their 3 years in Egypt. The sketches were later published as charming miniatures in Louis Reybaud, Histoire de l’expédition française en Égypte (1830-36), from which we pulled our portrait of Devilliers (second image).

You can learn more about the Egyptian adventures of Devilliers, Jollois, and their colleagues, at the page “Engineering Archaeologists” in our online exhibition catalog.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Signatures of the artists, “Jollois et Devilliers delt [delineavit]," detail of fourth image (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/1c574cfa-278e-419a-b293-1cd88cfe3878/devilliers5.jpg?w=762&h=594&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)