Scientist of the Day - Edmund Neville Nevill

Edmund Neville Nevill, an English astronomer and chemist, was born Aug. 27, 1849. Nevil came from a distinguished family, but his passion was observing and mapping the moon. In 1876, he published the only original English lunar map of the 19th century (German astronomers such as Wilhelm Lohrmann, Wilhelm Beer and Johann Mädler, and Julius Schmidt, had cornered the lunar map market up to that time). Since lunar mapping was not considered a genteel occupation, Nevill published under the name Edmund Neison. And as he used that name in all of his lunar activities, such as editing the publications of the Selenographical Society, we will use the name Neison as well for the rest of our discussion.

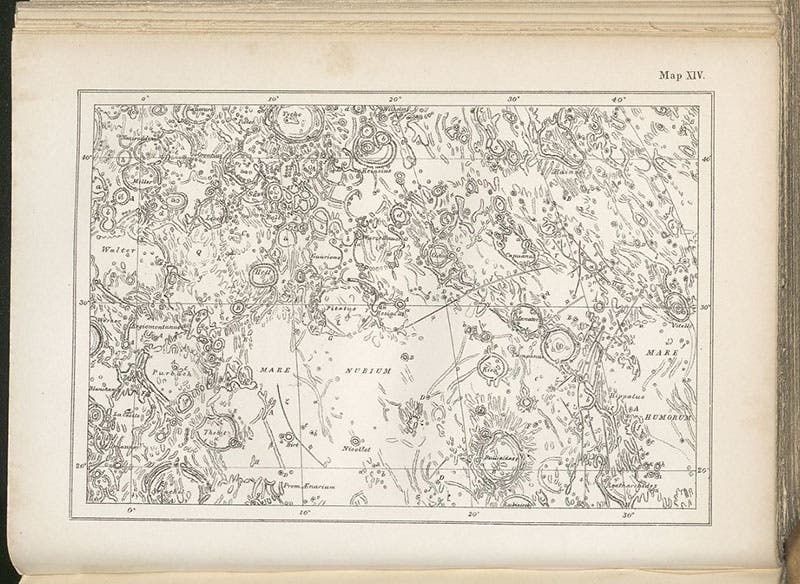

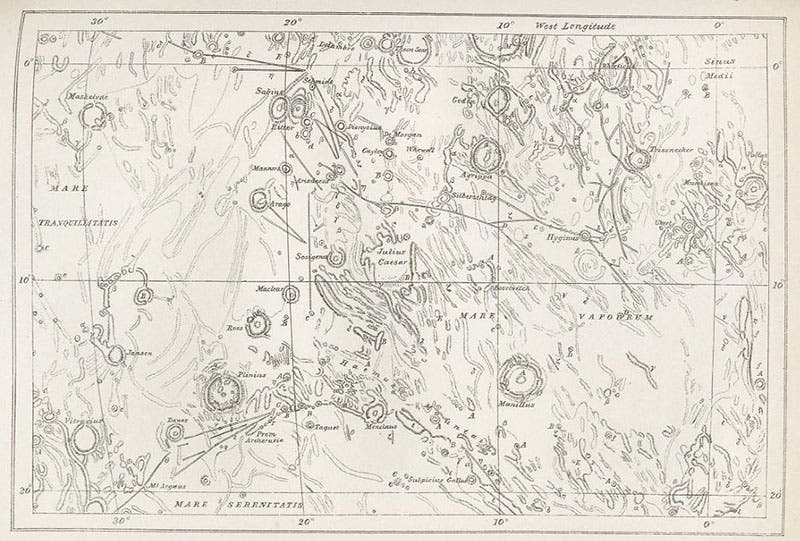

Neison's moon map appeared in 22 sections in his book, The Moon and the Condition and Configurations of its Surface (1876), which we have in our collections. It was drawn on a scale of 24 inches to the diameter of the moon, which he considered sufficient to convey all the detail that can be observed with an Earth telescope. His map was based on that of Beer and Mädler, and since that map was three feet across, Neison was, in effect, saying that the Beer and Mädler map contained more detail than is observable, or that the small details were invented. In fact, Neison said that explicitly.

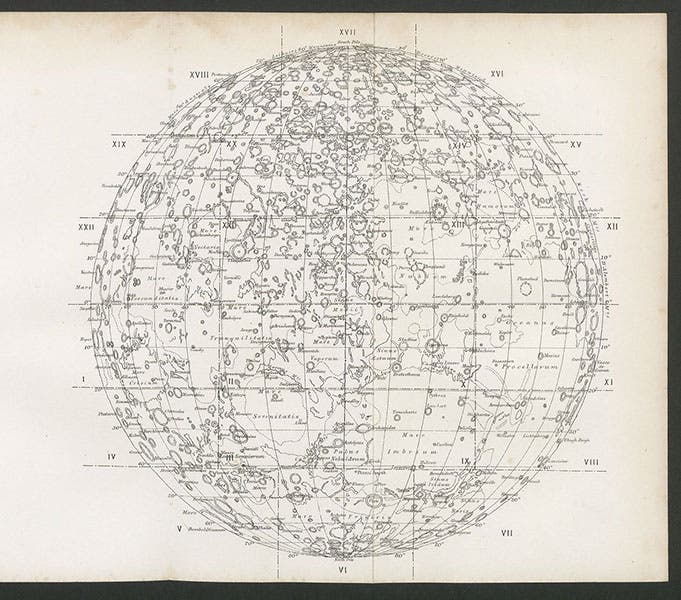

We show here two of Neison’s lunar map sections, Section XIV in the lunar highlands, centered on Mare Nubium and containing the crater Tycho at the top (second image), and Section II, which includes the Sea of Tranquility where Apollo 11 would later land (third image). In addition, we show a key to the location on the moon of the 22 sections, which also functions as a small diagrammatic lunar map (fourth image, above). South is at the top in all these maps, which was the custom at the time, since the moon appears inverted in a small refractor, the standard tool of the lunar observer.

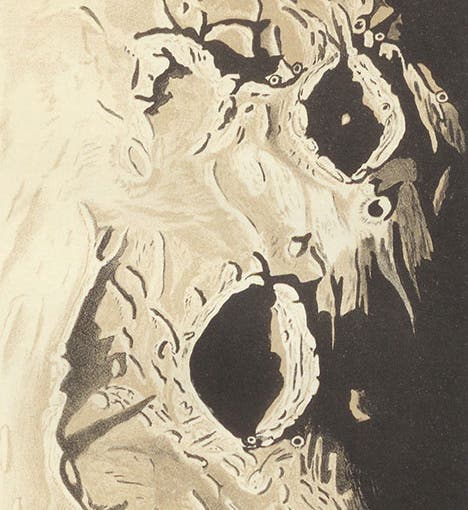

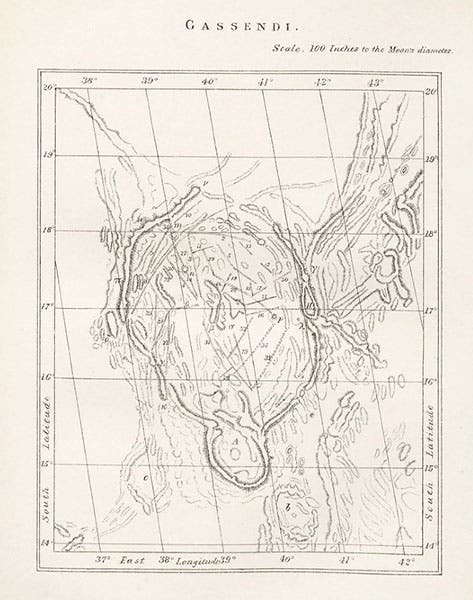

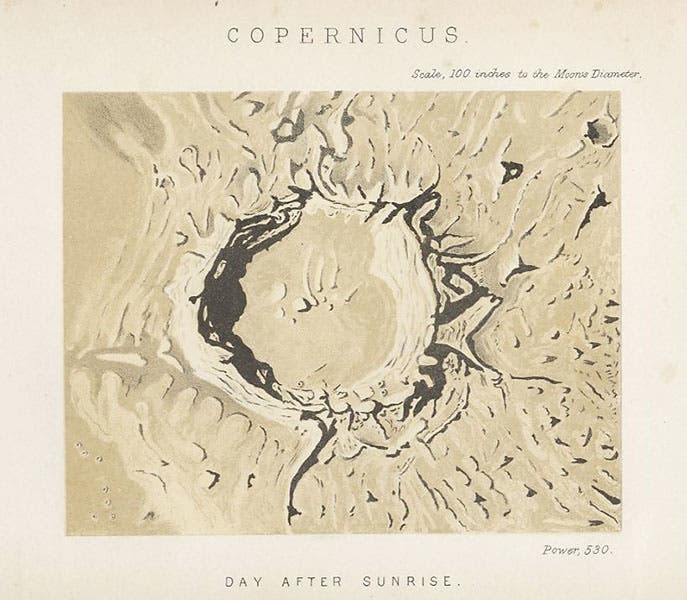

In addition to the sectional maps, Neison incuded several maps at a larger scale (thereby belying his claim that a 24" map can contain all the detail that can be observed). One of these is the crater Gassendi, which is shown at a scale of 100" to the diameter of the moon, or four times larger than the sectional maps (fifth image, above). For two areas of the moon, Neison shows a pair of tinted lithographs, also at the larger scale. One pair depicts the crater Plato at sunrise and again at noon, and the other pair shows the twin craters Godin and Agrippa under the same illumination conditions. The purpose was to demonstrate that a lunar crater will show quite different appearances, depending on the orientation of the light. We displayed Neison's drawing of Plato at sunrise in our exhibition, The Face of the Moon: Galileo to Apollo. The sunrise drawing of Godin and Agrippa we include here (first image). Finally, the frontispiece of Neison’s book is another tinted lithograph, of the crater Copericus, one day after sunrise (sixth image, below)

Hundreds of Neison's drawings and notes, made at the telescope, are preserved in the Library of the Royal Astronomical Society in London. I did not know this until Frank Manasek, a historian of lunar mapping, sent me the chapter of his forthcoming book that includes a discussion of Neison. Manasek illustrates his analysis with not only some of the printed maps like the ones we show here, but also a number of photographs of Neison's notebooks, including the page with an ink drawing of Gassendi, and the two drawings of Godin and Agrippa that the printed lithographs were based on. Manasek's book manuscript is titled “A Treatise on Moon Maps. Visual Studies on Paper, 1610-1910” and is in the process of being submitted for publication. It should be a major contribution to the history of lunar cartography when it appears in print.

It is often said that there is no portrait of Edmund Nevill/Neison, but there are at least two photos of him as a young man. We show the one that was not rights-protected (seventh image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.