Scientist of the Day - Edmund Beecher Wilson

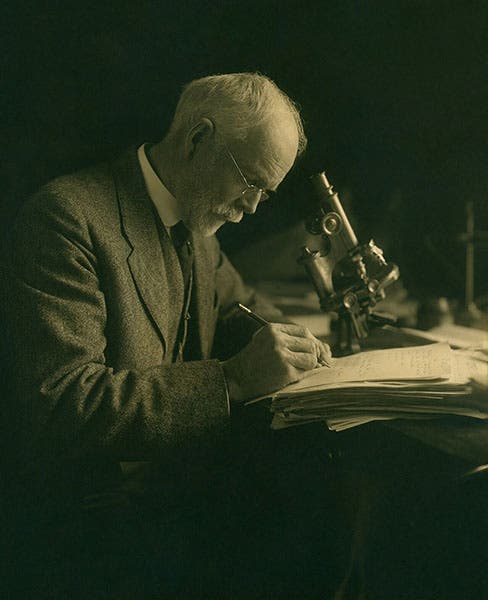

Edmund Beecher Wilson, an American zoologist and pioneer cell biologist, died Mar. 3, 1939, at the age of 82. He was born on Oct. 19, 1858, in Illinois, son of a judge. Wilson studied biology at Yale, and received his PhD from Johns Hopkins in 1881, one of the first advanced degrees granted by that fledgling research institution.

Wilson began teaching at Bryn Mawr College in 1885, a school associated with quite a few prominent cell biologists, although Wilson was the first. Then in 1891, he moved to Columbia University, becoming the invertebrate counterpart to Henry F. Osborn. Wilson remained at Columbia for the rest of his career.

Wilson was an interesting example of a man considered exemplary by all his colleagues and students, and eulogized when he died, but not really noted for any significant discovery. He did discover the importance of the Y chromosome in sex determination in 1905, but Nettie Stephens made the same discovery at the same time, saddled with a far greater handicap, her gender. Otherwise, Wilson led primarily by example.

As an instance, Wilson decided in 1882 to spend a year at the Zoological Station in Naples. This center for marine biology had just been established, and there was nothing like it – no Woods Hole yet – in the United States. As a budding cell biologist and embryologist, Wilson realized, before anyone else, that the cells and ova of marine animals like sea urchins and sea worms were much easier to study than the mammalian versions, and a marine biological station was just the place to find the necessary specimens. Many later cell biologists (and marine zoologists) followed Wilson’s lead.

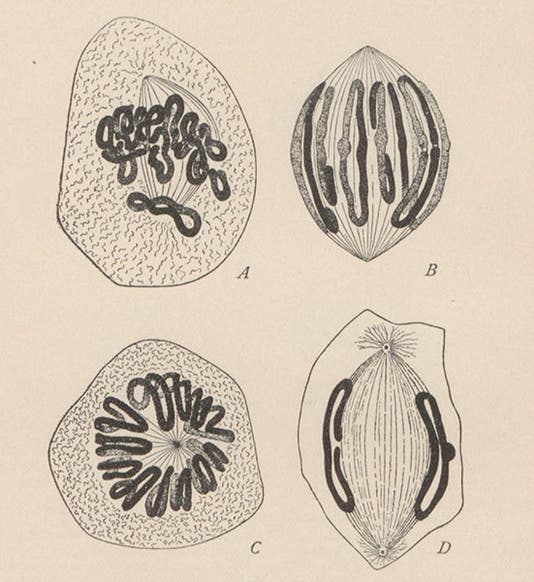

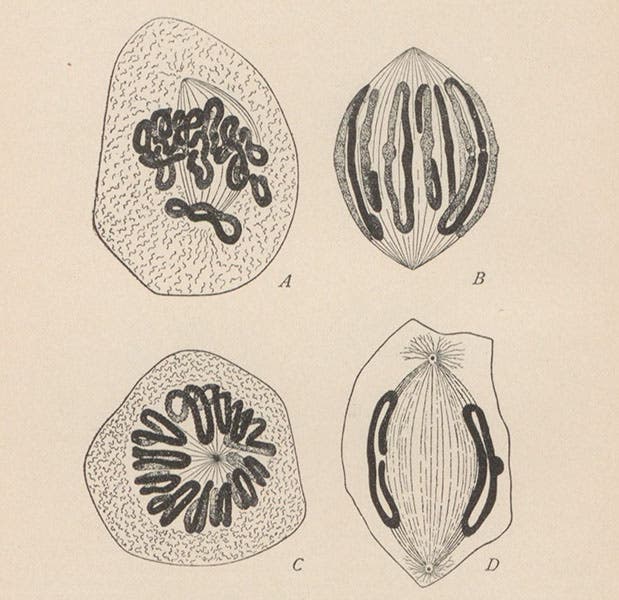

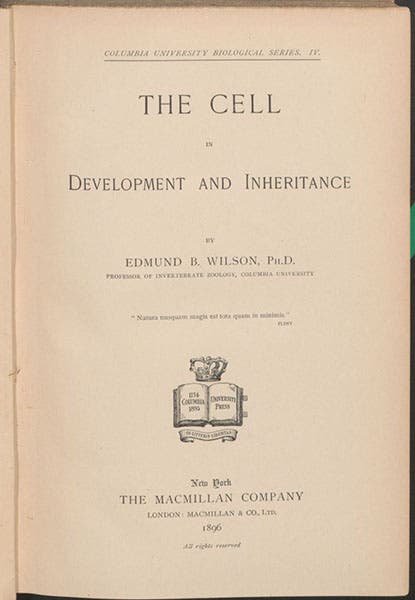

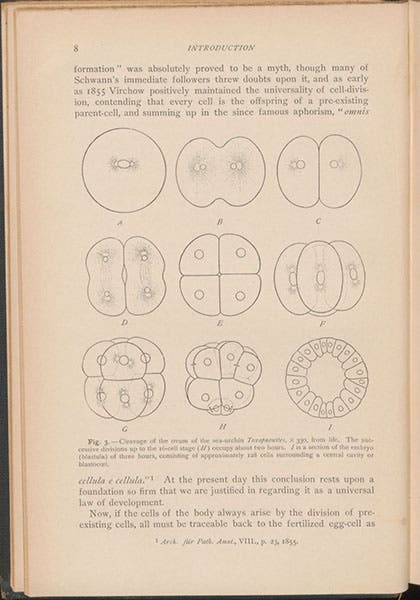

Wilson also realized that in a field as rapidly changing as cell biology, what students needed most was an up-to-the-minute textbook. He wrote such a book and published it in 1896: The Cell in Development and Inheritance. It was the most widely used textbook in its field for thirty years, an extraordinarily long time for a textbook in a fluid discipline, and the last edition (1925) won Wilson a medal. We have copies of the first and second (1900) edition of The Cell, and we digitized the first for this occasion, providing the images for this post. Our copies are well-worn, well-thumbed, and penciled-up, as a good textbook should be.

Wilson also inspired his students and colleagues to do great things. His student from Kansas, Walter Sutton, in 1902-03, discovered how chromosomes provide a physical explanation of Mendel's laws, which were rediscovered in 1900. Wilson's younger colleague at Columbia, Thomas Hunt Morgan, showed in 1915, in his studies of fruit-flies, that genes are on chromosomes. Both of these were epochal advances, to which Wilson's name is rarely attached, but for which he deserves a sizable share of the credit.

Fortunately for Wilson, he is not unsung in histories of genetics and cell biology. He is always mentioned in studies of Sutton, Morgan, Theodor Boveri (the German counterpart to Sutton, and a good friend of Wilson, who dedicated The Cell to Boveri), and in studies of turn-of-the-century genetics in general, even if writers are sometimes hard-pressed to say exactly what Wilson did that was so important. I hope we have managed to do so here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)