Scientist of the Day - Edme Jomard

Edme-François Jomard, a French topographical engineer and cartographer, was born Nov. 22, 1777. When he was just 21 years old, fresh out of the recently established École Polytechnique and enrolled in the École des Ingenieurs-Géographes, he was plucked from school by Joseph Fourier, advisor to Napoleon, and asked if he wanted to participate in an overseas adventure, to an undisclosed destination, where he would be accompanied by many other young engineers, cartographers, and naturalists. The cloak-and-dagger nature of the mission appealed to Jomard, and he signed on. A few months later, he was on his way to Egypt, along with 150 other scientists and 45,000 troops, as part of Napoleon’s 1798 invasion. Jomard would be away from home for three years, and during that time the young savants would not only survey the region along the Nile, but discover (and measure and draw) the fabulous ruined temples and tombs at Luxor, Karnak, Esna, Edfu, Dendera, and Philae. We discussed and displayed the scientific fruits of Napoleon's expedition in our 2006 exhibition, Napoleon and the Scientific Exhibition to Egypt, which you may view online.

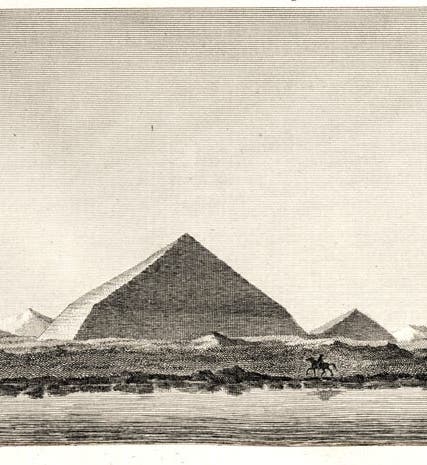

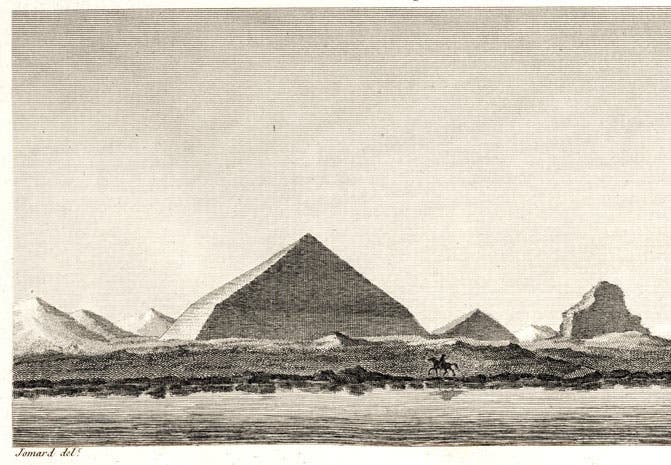

Jomard was not as involved in drawing antiquities as some of his friends, such as Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois and Edouard Devilliers du Terrage, but he was actively involved in the mapping enterprise. He was also one of the members of the Institute of Egypt, founded by Napoleon in 1798 on the model of the Institut de France. Jomard’s name is on one of the beautiful maps of Cairo that would eventually be published; we see here a detail that shows the house and gardens of Hâsan Kâchef in Cairo, which the Institute of Egypt took over (third image). Jomard also drew the stepped pyramids at Faiyum, which we sometimes forget about when we think of the Egyptian pyramids (first image).

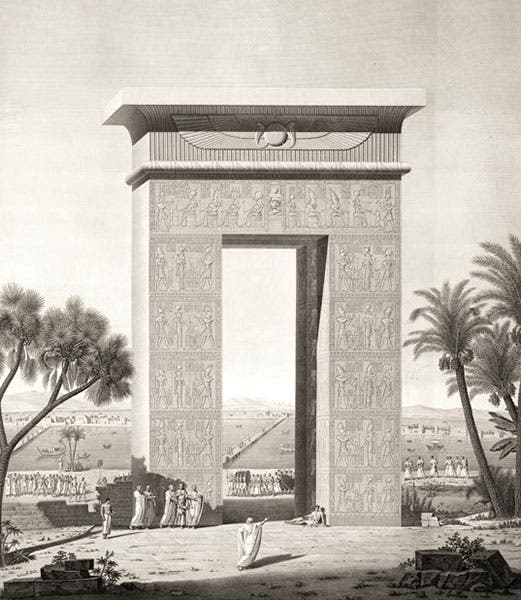

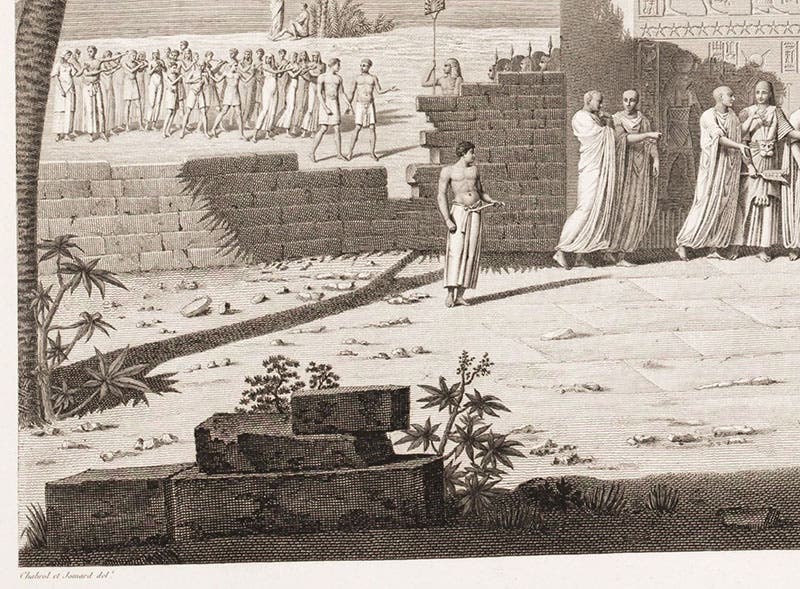

Jomard also took one stab at one of the favorite exercises of some of the topographical engineers. When they were tired of drawing ruins as they were now, they would restore the ruins to their former grandeur on paper, and populate them with imagined ancient Egyptians. Jomard and another colleague, Gaspard-Antoine Chabrol, drew a restoration of the North Gate at Dendera, the site where the engineers found the famous Zodiac of Dendera. We show a detail of the entire engraving (fourth image), and then a much-more enlarged detail of the lower left corner, where you can see the signatures of Jomard and Chabrol (fifth image).

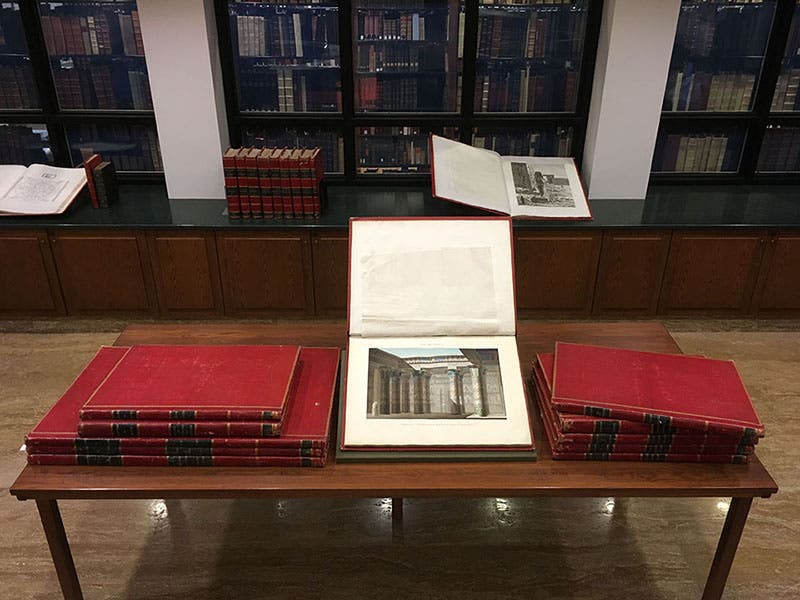

Jomard made his biggest contribution to Egyptian studies when, in 1807, he took charge of the project to publish the results of Napoleon’s expedition, after the first two editors had died in the saddle. All of the savants, while still in Egypt, had formed a company to organize, illustrate, and publish the fruits of their labors, and in 1802, Napoleon agreed to fund the enterprise, to the tune of 60,000 francs per year. There were as many as 36 full-time staff that Jomard presided over, many involved in making the 847 engravings that would grace the publication. The first volume of the Description de l'Égypte was published in 1809 (actually 1810, but they had promised Napoleon it would be out in 1809, so they just left that date in there). Jomard oversaw the work until the final atlas appeared in 1828. A complete set of the Description has 10 large quarto volumes of text and 13 folio volumes of plates, three of them super-folios that contains the largest sheets of paper ever made for printing purposes. You can see our entire set laid out for a photo-shoot in the Library’s history of science reading room, in front of our glass vault (sixth image).

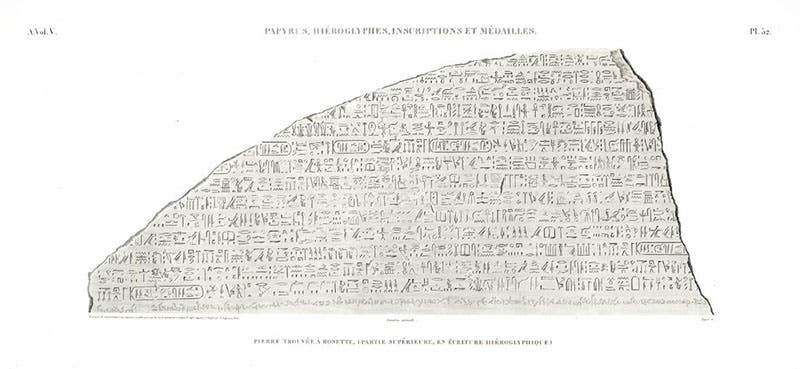

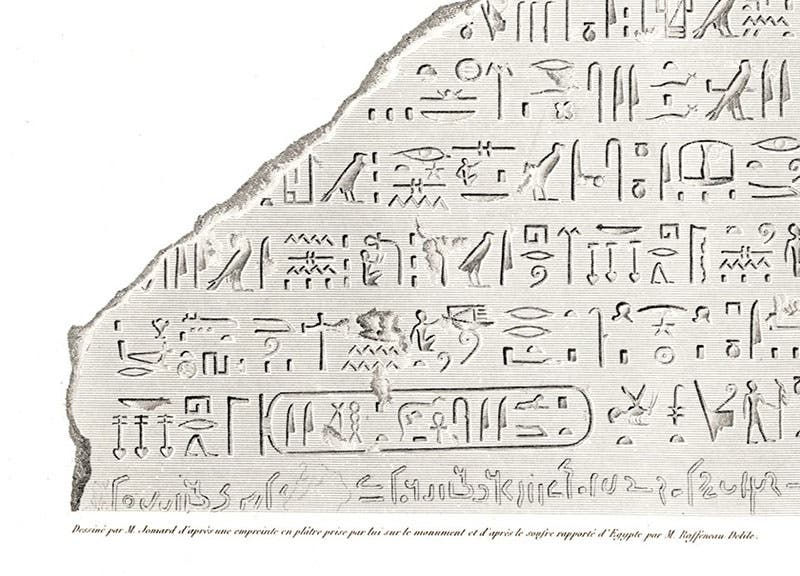

Five of the folio volumes of the Description were titled Antiquités. These contain dramatic engravings of every site they visited – elevations, ground plans, even restorations that imagined what the places would have looked like in the time of the Pharaohs, such as our fourth image. One of the Antiquités volumes has three plates of the three sections of the Rosetta Stone, which had been found by Pierre Bouchard in 1799 (see our post on Bouchard). While in Egypt, the members of the Institute of Egypt had made prints directly from the stone, both relief and intaglio, and had taken casts as well, which was fortunate, since the British confiscated the Rosetta Stone as booty in 1801 and took it back to the British Museum, where it still sits. Everyone was aware that the Rosetta Stone was likely to be the essential key to deciphering hieroglyphics, since it seemed to contain the same proclamation carved in three different languages: Greek, Demotic, and Hieroglyphic. Jomard took a personal interest in seeing that the engraving of the top third, the hieroglyphic portion, was as accurate as humanly possible. The engraving was published in 1822, in the fifth volume of the Antiquités. Jomard took great offense when Jean-François Champollion, out to decipher hieroglyphics himself, charged that the engraving was inaccurate. We show here the plate with the hieroglyphics section (seventh image), and a detail that shows some of the hieroglyphics that Jomard had so carefully copied, as well as his signature, and an explanation that the engraving was based on a sulfur cast made in Egypt by Adrien Raffeneau-Delile and a plaster cast made in London by Jomard himself (eighth image).

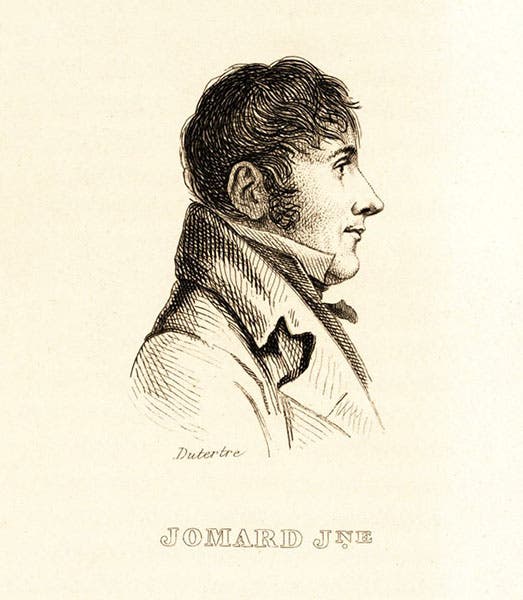

Jomard would have quite a productive career, being one of the founding members of the Société de Géographie in 1821, the world’s first geographical society, but nothing would top the excitement of the Egyptian years. We have a good likeness of the 23-year-old Jomard in Egypt, since one of the expedition artists, André Dutertre, took it upon himself to sketch profiles of nearly all the savants (including Napoleon), and these were published by Louis Reybaud in his 10-vol. history of the Egyptian expedition (1830-26) which we have in our collections. Dutertre’s drawing of Jomard is our second image.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.