Scientist of the Day - E. O. Wilson

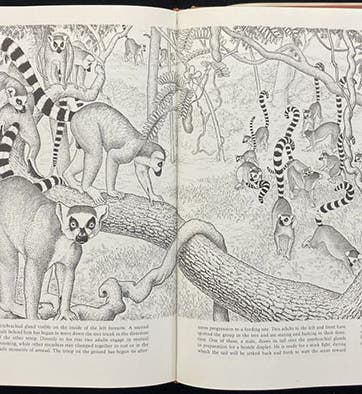

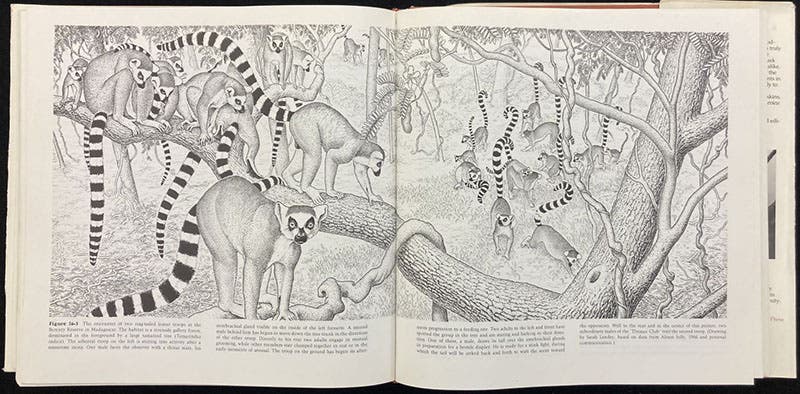

Two troops of ring-tail lemurs interacting in Madagascar, pen or pencil drawing by Sarah Landry, in Sociobiology: A New Synthesis, by E. O. Wilson, pp. 532-33, Harvard University Press, 1975 (author’s copy)

Edward Osborne Wilson, an American biologist, entomologist, and ecologist, was born in Alabama on June 10, 1929. Wilson, who published his books (and there were many of them) as E. O. Wilson, was the world's leading expert on ants. As a child, he was drawn to studying and collecting nature, and when he was blinded in one eye at the age of 7 in a fishing accident, he chose to concentrate on insects, which he could see quite well up close, with his one good eye. He attended the University of Alabama, then switched to Harvard for graduate work in entomology, where he ultimately joined the faculty, teaching there from 1956 to 1996. He was also curator of entomology at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology from 1973 on, taking that position in the same year that Stephen Jay Gould, 12 years his junior, became curator of invertebrate zoology.

Wilson made many trips to places like Polynesia and Central America to collect ant specimens, which he studied both in the field and back in the entomology lab at Harvard. He was especially interested in ant behavior and ant society, and its evolutionary origins. He worked for many years at Harvard with German entomologist Bert Hölldobler, and before Hölldobler left to go back to Würzburg to head his own lab, the two decided to write a book on ants. They first intended that it be a popular book for the general public, but Wilson realized that the two of them knew more about more species of ants than anyone else in the world, and so they decided to write the definitive book on ants, containing the sum total of their combined knowledge. They didn't waste a lot of time thinking of a catchy title; it was published in 1990 as The Ants. Amazingly, it won the Pulitzer Prize for general non-fiction, the second such prize Wilson was awarded.

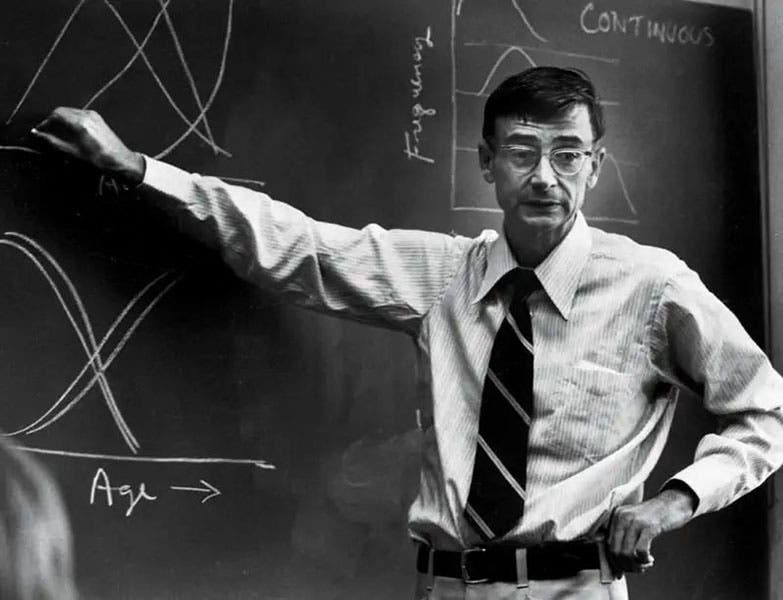

Front dust jacket, Sociobiology: A New Synthesis, by E. O. Wilson, Harvard University Press, 1975 (author’s copy)

But the book for which Wilson is best known (and which did NOT win a Pulitzer Prize) was a hefty tome called Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, published in 1975. I own this book – I bought it in those pre-Amazon days from a local bookshop in Kansas City and somehow got it home, which was not easy, since it is fully a foot square and two inches thick and weighs in at 5 pounds. I did not read much of it at the time, but I remember being fascinated by many of the illustrations, which were often pencil or pen drawings, occasionally double-page, such as the troop of lemurs (first image). I found them quite striking, and still do. Pencil drawing is an under-appreciated scientific art form.

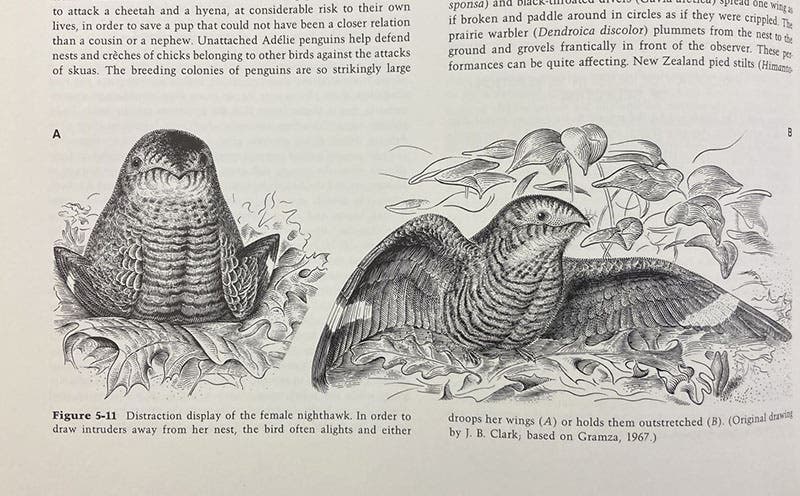

Distraction display of the female nighthawk, pen or pencil drawing by J. B. Clark, in Sociobiology: A New Synthesis, by E. O. Wilson, p. 122, Harvard University Press, 1975 (author’s copy)

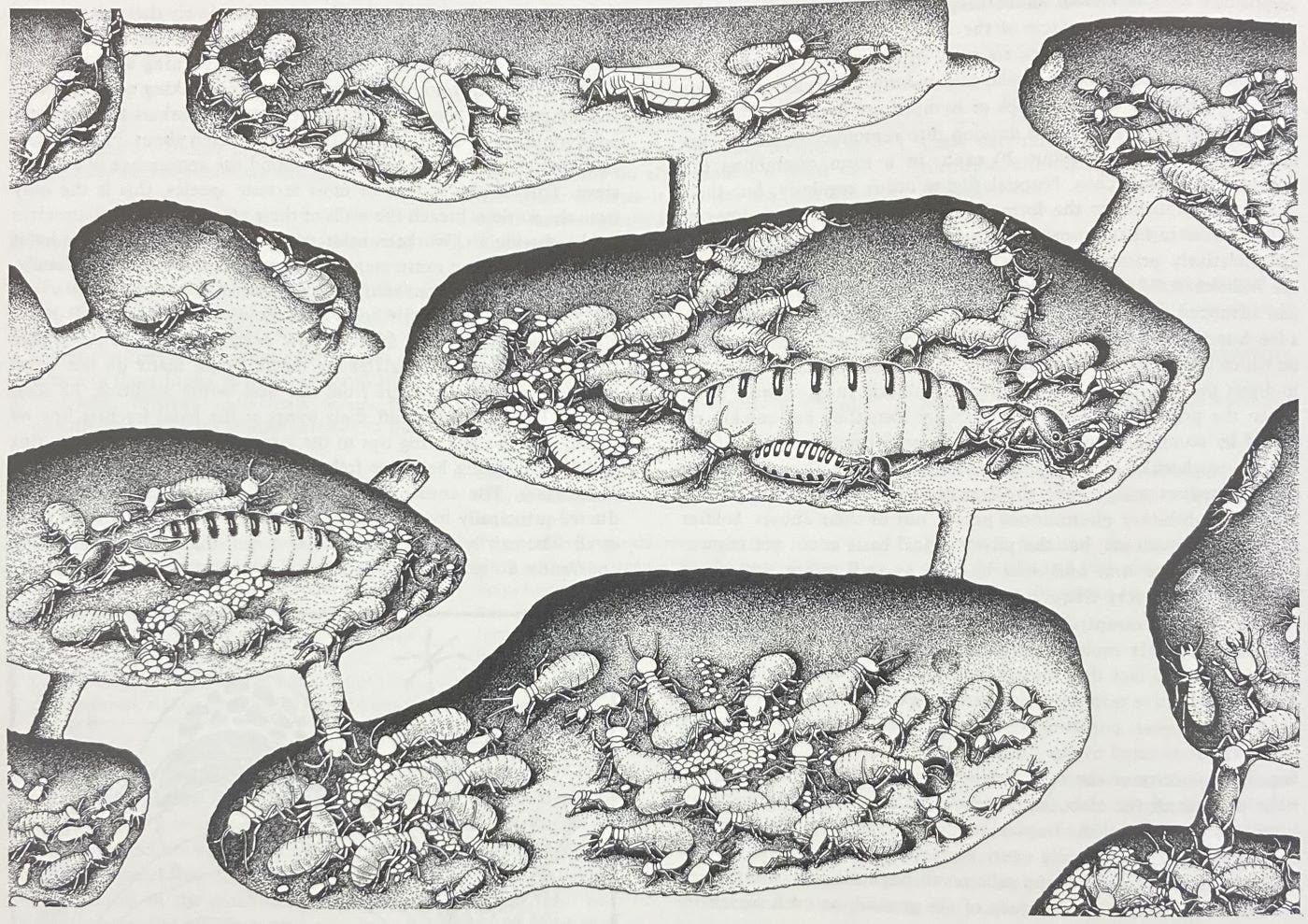

The book is the study of animal social behavior and its genetic origins. Wilson discussed a variety of behaviors, such as altruism, and why the sacrifice of an individual’s personal genes might make evolutionary sense for those genes in the long run. The book begins, unsurprisingly, with social insects, but soon moves to other social animals, such as birds, primates, and, in the last chapter, humans.

Interior of the nest of Amitermes hastatus, a social termite of South Africa, pen or pencil drawing by Sarah Landry, in Sociobiology: A New Synthesis, by E. O. Wilson, p. 436, Harvard University Press, 1975 (author’s copy)

The word "Sociobiology" was not coined by Wilson, but he certainly made it popular, and controversial. Wilson argued that, even for humans, behavior is rooted in our genes, and nearly everything we do should be studied as a solution to an evolutionary problem. Unfortunately, evolutionary determinism can be used to justify, or at least explain, many unsavory aspects of human behavior, including racism. Consequently, Wilson's book was roundly condemned by many left-leaning biologists, including Stephen Jay Gould, working in the same museum as Wilson. Wilson defended his book, and denied that it included any support for racism, and he had many supporters, but the controversy has lingered to the present day, almost 50 years later. Even after Wilson’s death in 2021, some historians have been combing through his papers, determined to find evidence that Wilson, if not a racist in public, had racist sympathies in private. This seems an unfortunate exercise to me.

I prefer to form my opinions of Wilson from his books and his public persona, which is that of a well-spoken gentleman with a fascinating personal history. A series of video interviews, each less than 5 minutes long, was recorded around 2005 (I would guess) and can be found on YouTube, where Wilson talks about his childhood, or writing his book on ants, or on what it takes to be a good scientist. Here is one of them, about his discovery of fire ants in Alabama, and you can see the others, 15 in all, listed on the YouTube page, so you can take your pick if you want to watch more. There was also a PBS Nova program that I watched, Lord of the Ants, but I cannot now find it online. I do remember enjoying the charming and enthusiastic E.O. Wilson who came across in that program.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.