Scientist of the Day - Democritus of Abdera

Democritus of Abdera, a pre-Socratic philosopher of ancient Greece, lived from about 460 B.C.E to about 370 B.C.E. Abdera was a polis in Thrace, on the north shore of the Aegean Sea, not too far from the Bosporus Strait, and a long way from Athens, where Socrates would teach, and die in 399 B.C.E., and Plato and Aristotle would set up their schools in the 4th century B.C.E.

Democritus was considered by Aristotle as one of the two fathers of atomism, the other being Leucippus, supposed to be the teacher of Democritus. The problem with Leucippus as a father of atomism is that we do not know anything about him – where he came from, what he wrote – we are not even sure that he really existed . We are more certain about Democritus, and so our discussion of ancient atomism will be credited to Democritus, and we will say no more about Leucippus.

In earlier posts, we discussed the Eleatic School of natural philosophy, begun by Parmenides of Elea and continued by Zeno of Elea. The Eleatics attacked the Ionians – philosophers such as Thales of Miletus, Anaximander of Miletus, and Heraclitus of Ephesus – who proposed that the world began with a single kind of matter (water for Thales, apeiron (the undefined) for Anaximander), which then, under the influence of qualities such as hot and cold, wet and dry, became the many kinds of substances we see in the world today. The Eleatics challenged the idea that one substance could become many substances, without the prior existence of some other kind of matter to mix with it, or some other kind of operator to act upon it. They further argued that change is an illusion (Zeno’s forte), and that a void, which has no properties, cannot exist.

Several natural philosophers responded to the Eleatic challenge with pluralistic theories of matter. Anaxagoras of Clazomenae suggested that there are an infinite number of basic particles of matter – seeds, he called them, each with different qualities – that make up larger-scaled substances such as wheat and wine, flesh and bone. Empedocles of Agrigentum started with four basic kinds of matter instead of one – earth, water, air, and fire – and explained all other substances as compounds of the four elements and the four qualities.

Democritus proposed that all substances are made of tiny particles that he called atoms (which means indivisible in Greek). Atoms differ in size and shape, but materially, they are all the same. There are an infinite number of atoms in the universe, and they move about in empty space. They can take up different arrangements in the void, and these differing arrangements are what explain differences in substance. The movement of atoms is entirely random, undirected by any cosmic force.

Democritean atomism was unacceptable to most ancient Greek natural philosophers, such as Aristotle, because it describes an atheistic universe, without final causes. However, atomism became quite popular in 17th-century Europe, when it was forced into a Christian framework (God created atoms and gave them their initial impulse, said Pierre Gassendi), and Democritus became an intellectual hero in the 19th century, when it began to appear that his atomic hypothesis actually did describe the world.

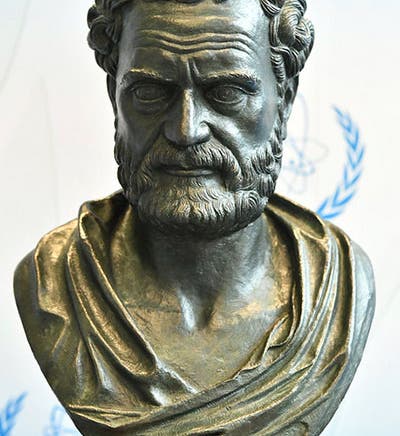

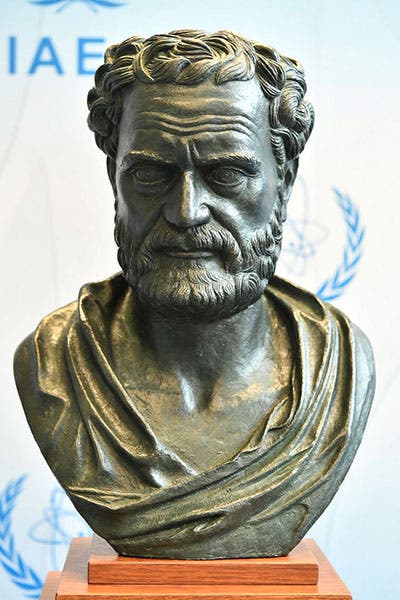

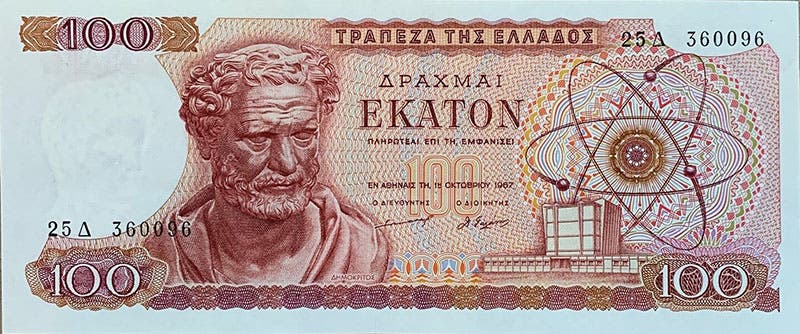

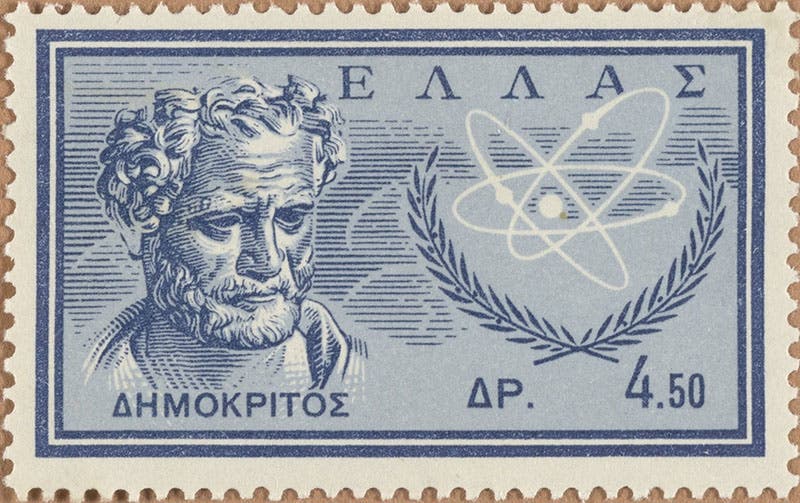

The atom of modern physics bears little resemblance to the atom of Democritus, so he is back to being just one of a dozen brilliant speculators who preceded the age of Plato and Aristotle. But modern Greeks are quite partial to Democritus, and somewhere – probably in the National Museum of Athens – there is a handsome bronze bust that is believed to represent Democritus. It has appeared on Greek currency (second image), on Greek postage stamps (third image), and most recently, a copy was presented in 2020 by the Greek government to the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna (first and fourth images).

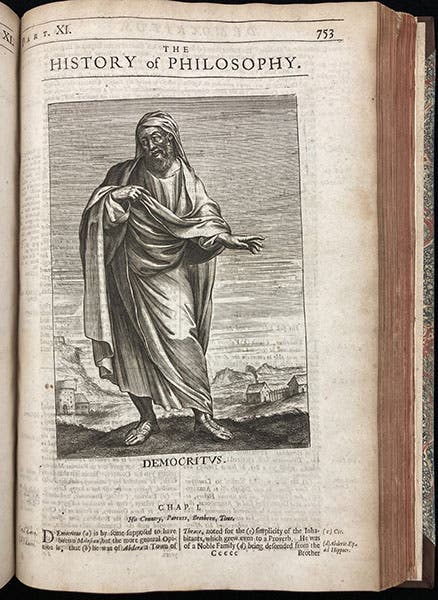

We have in our Library an entirely different (if equally fanciful) representation of Democritus, in Thomas Stanley’s The History of Philosophy: Containing the Lives, Opinions, Actions and Discourses of the Philosophers of Every Sect (2nd ed., 1687), a book that we introduced in our recent post on Empedocles. We show the entire engraving as our fifth image, just above, and a detail of the head as our sixth image, below. At least now you have a choice for your mental image of Democritus.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.