Scientist of the Day - David Wilkinson

David Wilkinson, an American machinist, was born Jan. 5, 1771. Wilkinson was one of the fathers of both the American textile revolution and the American industrial revolution as a whole. Unlike his English counterpart, Richard Arkwright, the textile mill founder whom we profiled several days ago, Wilkinson was a machine shop kind of guy. A native Rhode Islander, he was raised in the shop of his blacksmith father and grew up with tools in his hands. Indeed, one of his earliest achievements – and to modern machinists, his greatest one – was the invention of the automated screw-cutting lathe. One of the impediments to any kind of mass production was the nonuniformity of screw threads. As long as they were cut individually, by hand, they were going to be different, each screw or bolt from another, and hence not interchangeable. In 1798, Wilkinson was granted a patent for a lathe that used one threaded rod as a lathe guide for automatically cutting threads on a blank rod. All of the threaded rods were identical to the master. A similar machine was invented about the same time in England by Henry Maudslay. There is no evidence that either man knew of the other's work. Six of Maudslay's screw-cutting lathes survive, and none of Wilkinson's, so Maudslay gets more acclaim than Wilkinson for the invention. But there is no doubt that American machine shops followed the lead of Wilkinson, not Maudslay.

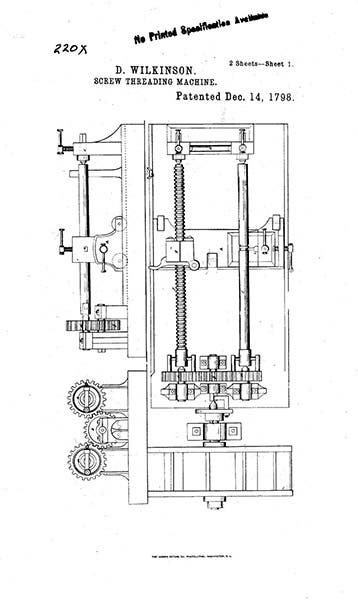

Wilkinson’s patent for his “screw-threading machine” of 1798 survives, I am not sure how, since most patents before 1836 were destroyed in the fire of that year, but some version of the patent is available on Google Patents, and we show it here (third image, below).

In the early 1790s, a recent transplant to Rhode Island, Samuel Slater, was building a textile mill along the Blackstone River in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, now part of north Providence. He had trouble finding craftsmen to make the machinery he needed. Fortunately, he met Wilkinson, who proceeded to manufacture most of the equipment used in the Slater Mill, the first water-powered textile mill in the Americas, opened in 1793. In 1810, Wilkinson built his own textile mill right next to Slater's, using the same water sluice for power (first image). This was not competition – Wilkinson had married Slater's sister, and the two were good friends – but rather specialization. Textile production requires carding machines, spinning machines, and power looms, and Wilkinson's Mill took over some of those processes. And on the first floor, he built a machine shop, to service all the machines in the entire complex (fourth image, just below).

The Wilkinson mill, some 3 1/2 stories tall and built of local stone, is still in place (as is Slater's Mill). After centuries of disuse, it was restored in the 1970s and became part of the Old Slater Mill Historic District. It was also designated a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in 1977. The machine shop has been reconstructed, with its belt-driven machines powered by an undershot waterwheel. I have not visited Wilkinson's Mill, but I intend to, the next time I am back in New England. Fortunately, a visitor to the District has put up some dramatic photos of the Wilkinson Mill shop on the Practical Machinist website, and I have borrowed two of them for this post, one showing the undershot waterwheel in operation, and the other an upward view of the network of belt-drives on the ceiling of the machine shop (fifth and sixth images, below). One can almost hear the slap-slap sound of leather on pulleys over the hum and sometimes clatter of the machinery.

During the economic hard times of 1829, Wilkinson was forced to sell his mill and machinery. During the economic hard times ot the pandemic of the past few years, the Old Slater Mill Association, the non-profit that owned the buildings of the Slater Mill Historic District, could not keep up with expenses, and its property was acquired by the National Park Service in 2021. As far as I know, both Slater's Mill and Wilkinson's Mill will stay open and accessible to the public.

I do not know the source of the one portrait of Wilkinson that is shows up on various websites. One hopes that it is authentic. But it would be nice to know where it is, and who painted it, and when.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.