Scientist of the Day - David Bruce

David Bruce, a Scottish physician and microbiologist, died Nov. 27, 1931, at age 76. He was actually born in Australia, but his Scottish parents returned to Scotland when he was young, and Bruce grew up in Stirling. He then studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, and practiced for a short while, but gave up private practice to join the Army Medical Service in 1883. He would remain a military physician for the rest of his career.

In 1884, Bruce was stationed in Malta, where he encountered patients with a debilitating disease that was locally called Malta fever, and elsewhere was known as Mediterranean fever. The cause was unknown, but the effects were notable: fever, excess sweating, muscle and joint paint, and often gastro-intestinal problems. The symptoms never entirely went away, and the disease could be fatal.

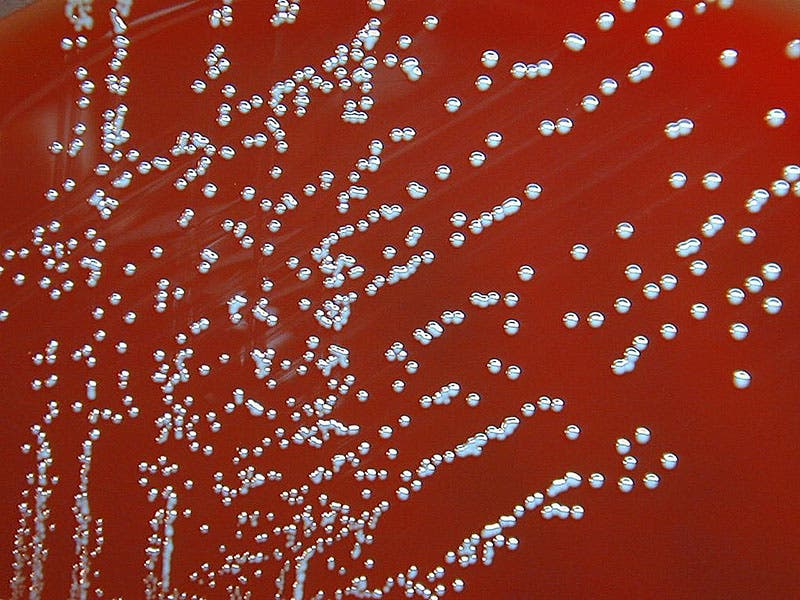

Bruce headed up a Royal Army investigative team known as the Mediterranean Fever Commission, and in 1887, he discovered bacteria in the liver of deceased victims of Malta fever, which were roughly spherical in shape, and which he called a coccus. Later investigators saw the bacterium as more rod-shaped, and bacteriologists settled on coccobacillus (“nearly spherical rod”) as the final designation. It was present in patients with Malta fever, and absent in those who did not have Malta fever and met all the other criteria for disease causation. The bacteria were quite active under the microscope, and for a while the disease was known as undulant fever from their squirminess. The disease was later named brucellosis, in Bruce's honor, if it is an honor to have a disease named after you. The coccobacillus itself was named Brucella (second image). It is often said that Bruce discovered that humans usually got the disease from unpasteurized goat's milk, but that discovery was actually made later by one of Bruce’s co-workers, Themistocles Zammit .

The group portrait of the Mediterranean Fever Commission is one of the great group portraits of the 19th century, at least in terms of sharpness (first image). This print is in the Wellcome Collection in London. Bruce dominates the photo at the center. Themistocles Zammit is the individual at back-row left.

Bruce had secured a place in infectious disease history, but he wasn't done. Restationed to Uganda, Zululand, and South Africa, he discovered in 1903 that sleeping sickness is caused by a trypanosome, a protozoan, which is carried by the tsetse fly. The disease was soon named, more formally, African trypanosomiasis, and the infectious agent, Trypanosoma brucei.

Bruce was eventually promoted to Major-General and received all the medical awards one could receive, except the Nobel Prize. He served in the First World War and then retired to Sterling. His wife Mary, who had collaborated with Bruce during many of his medical investigations, died on Nov. 23, 1931, and Bruce himself passed away during her funeral ceremony just four days later. They were buried in Valley Cemetery in Stirling beneath a memorial cross (fourth image)

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.