Scientist of the Day - Daines Barrington

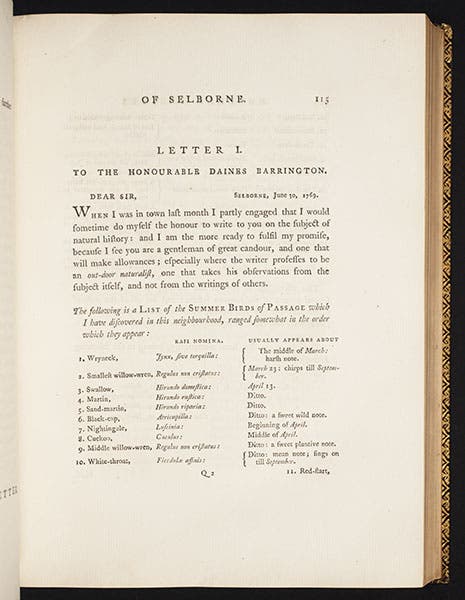

Daines Barrington, an English lawyer, antiquary, and naturalist, died Mar. 14, 1800; his birthdate was not recorded. If Barrington is known at all, it is because he was the recipient of some 66 letters from the noted naturalist Gilbert White, letters than ended up in White's Natural History of Selborne (second image). We profiled White in this space not quite two years ago; his Natural History of Selborne, first published in 1789, is the all-time best seller of all English works of natural history and has brought Barrington a kind of indirect immortality that he probably never envisioned as a mere letter recipient.

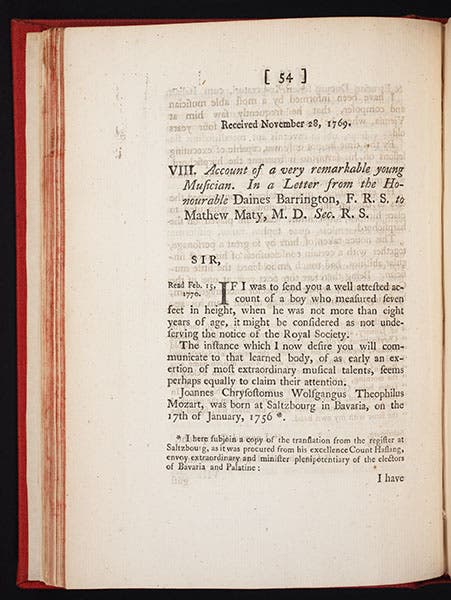

But Barrington has another claim to fame, known to musicologists, but not to most of the rest of us. In 1769, he wrote an account of an encounter with a young Austrian musical prodigy whom he had seen in England, and he published that account in the oddest of places, the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, the world's oldest scientific journal (third image). The young musician was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Mozart and his father Leopold were on a concert tour in England in 1765 when Barrington was invited to the residence at which they were staying. Mozart was nine years old at the time. Barrington had heard of the precocious youngster and had seen him in concert, and so when asked to visit, he came prepared – he brought sheet music for a duet, written by a friend and unknown to Mozart, which had two vocal parts and three string parts, written in three different clefs, one of them a seldom-used counter-tenor clef. Barrington describes in his review how Wolfgang placed the music on the harpsichord and proceeded to play the three string parts and sing the upper voice flawlessly, leaving it to his father to sing the lower part, not so flawlessly. Barrington points out how difficult this is, to sight-read three different clefs at one time – he says it is like trying to read Greek, Hebrew, and Etruscan at the same time. Some have wondered, Barrington goes on, whether Mozart might be much older than his appearance suggests, to be capable of such musical miracles. Such suspicions were laid to rest, at least for Barrington, when, during a lull in the festivities, Mozart ran about the room "with a stick between his legs by way of a horse."

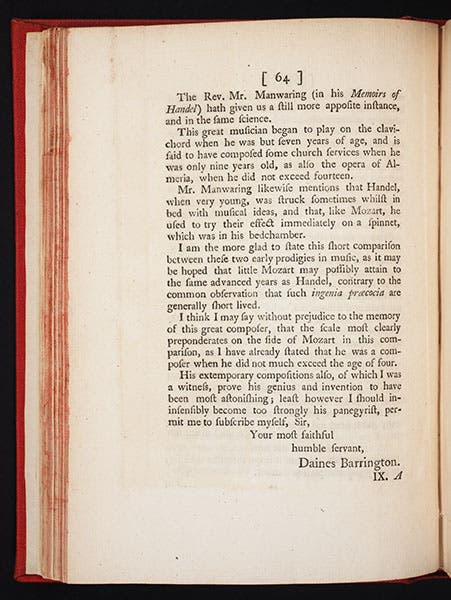

There is a poignant note in the last paragraph of Barrington's review, after he has discussed the precocity of George Frederick Handel: "I am the more glad to state this short comparison between these two early prodigies in music, as it may be hoped that little Mozart may possibly attain to the same advanced years as Handel, contrary to the common observation that such ingenia praecocia are generally short-lived” (fourth image). Barrington's wish was not to be realized; Mozart died just two years after the Natural History of Selborne was published, and nine years before Barrington himself passed away.

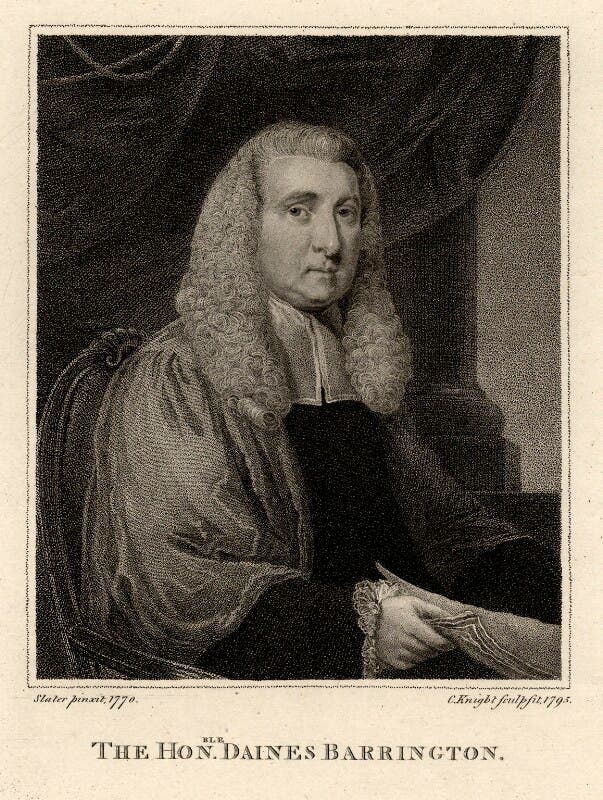

There is a pastel in the Condé Museum that shows the Mozart family on tour in 1763, two years before Barrington’s encounter (first image). The engraved portrait of Barrington (fifth image), made about the time he wrote his review of Mozart, is in the National Portrait Gallery of London.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.