Scientist of the Day - Cyrus Field

Cyrus West Field, an American businessman, died July 12, 1892, at the age of 72. Field made a fortune as a paper manufacturer in New York and retired at the age of 34, but he became quite excited by the potential of the new telegraph, made public by S.F.B. Morse in 1844, and he and Morse became close friends. Field was approached in 1854 and asked if he wanted to help finance a telegraph cable from Newfoundland to New York City. Supposedly, while looking at the route of the cable on a globe in his Gramercy Park home in New York City, he thought that it wouldn't be that much harder to lay a submarine cable from Newfoundland to the western tip of Ireland. Field wondered if it were technically possible to send a signal along 2000 miles of submarine cable, and when Morse assured him it was, Field was off and running.

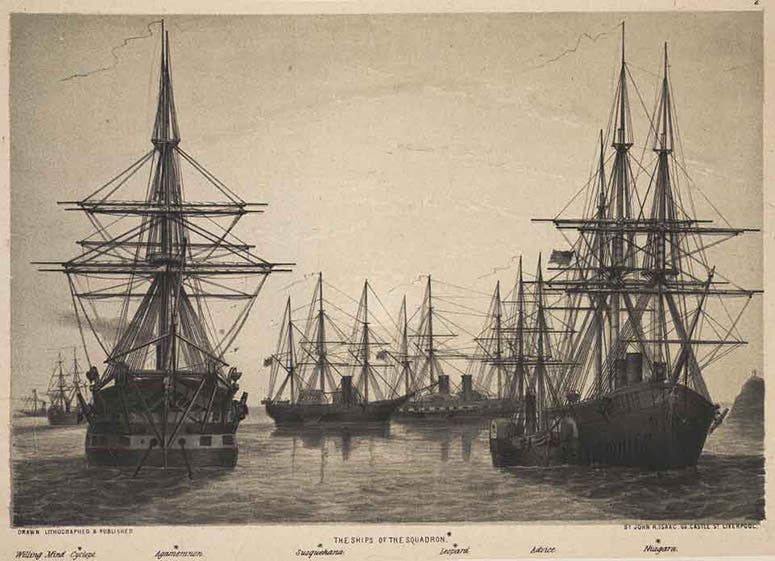

He formed a small syndicate, including Peter Cooper, acquired financing, and set out to lay a submarine cable across the Atlantic Ocean. At that time, several short cables had been laid, across the English Channel for example, but those were usually less than 20 miles long. It is difficult to say which was harder – designing the cable, which had to be light enough to maneuver but strong enough to support several miles of its own weight as it was being laid, or finding large enough ships and developing methods to lay cable across the ocean floor. The first attempt was made in 1857, using a U.S. ship named the Niagara and a British ship called the Agamemnon, with the 2000 miles of cable divided between them (third image). They laid out 300 miles of cable, starting from Ireland, before the cable failed and broke.

The first “cable squadron” setting up from England in 1857; the English cable-bearing ship Agamemnon is the large one at the left; the American ship Niagara is at the right, tinted lithograph in Laying the Atlantic Telegraph Cable from Ship to Shore: A Series of Sketches Drawn on the Spot, by John R. Isaac, 1857-58 (Linda Hall Library)

In 1858, they tried again, this time starting from the middle of the Atlantic and going both ways. The first time, the cable broke after 6 miles; they tried again, the next day, and laid 80 miles before failure; two days later, they regrouped, and this time managed 225 miles before the signal ceased. They returned to England and were going to quit, but Field pointed out that they had plenty of cable and a month left of the summer and nothing to lose, so they decided to have one more try. Starting on July 29, the Niagara and Agamemnon went their opposite ways, and one week later, on Aug. 5, 1858, a signal was sent across the Atlantic. It was a public sensation beyond imagining today, that the Queen of England could send a message to the American President in a matter of hours (it took a while for the early signals to be sent). Cyrus Field was the hero of the hour. Unfortunately, the 1858 cable failed about three weeks later, and Field's reputation lost a little of its luster, but he was nothing if not determined, although he had to wait until after the Civil War to make another attempt.

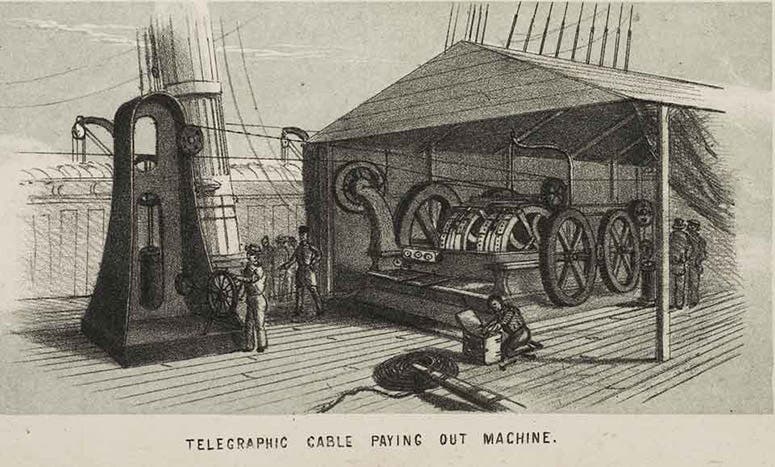

The cable-paying-out machinery on board the Agamemnon, tinted lithograph in Laying the Atlantic Telegraph Cable from Ship to Shore: A Series of Sketches Drawn on the Spot, by John R. Isaac, 1857-58 (Linda Hall Library)

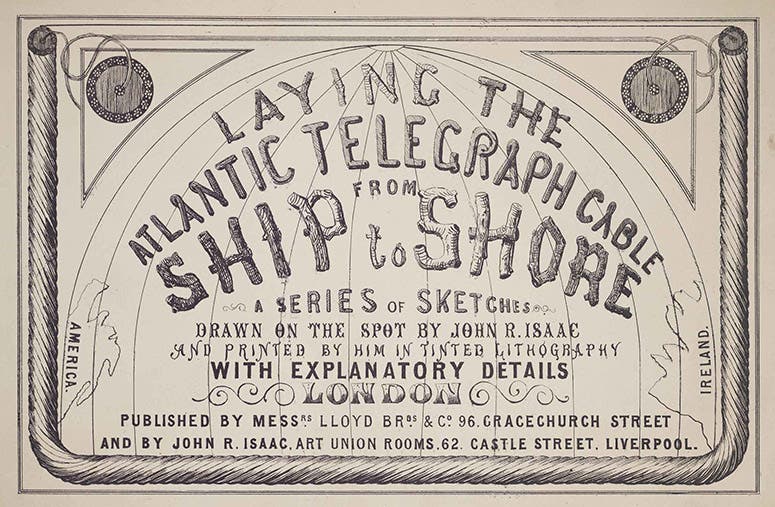

Lithographed title page, Laying the Atlantic Telegraph Cable from Ship to Shore: A Series of Sketches Drawn on the Spot, by John R. Isaac, 1857-58 (Linda Hall Library)

That opportunity came in 1865, and this time Field and his syndicate had a new ship to carry their cable – the Great Eastern, an enormous steamship built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel and launched in 1858. It was so capacious that it could carry the entirety of the 2000 miles of cable in its hold. The laying of the 1865 cable proceeded smoothly until about half-way across, when the cable broke. This happened more often than one might think; usually, the cable could be retrieved by a grapple, spliced back together, and the laying could proceed. This time, however, the cable on the ocean floor resisted all attempts at grappling. They had to give up for the season. Next year in 1866, they were back at it, again steaming from Ireland to Newfoundland and paying out cable as they went, and this time, they made it all the way across. On July 27, 1866, the cable was taken ashore at Heart’s Content on Trinity Bay in Newfoundland, and a signal was successfully sent back to Valentia in westernmost Ireland. The Atlantic had been bridged by telegraphy, and this time the cable did not fail. On the way back to England, they laid a second cable, successfully retrieved the broken cable of 1865 in the mid-Atlantic and spliced it onto the new one, and now the world had two trans-Atlantic cables. It is hard for us to imagine how much that changed the worlds of business, commerce, and statesmanship.

![Title page, chromolithograph by Robert Dudley, in The Atlantic Telegraph, by William Howard Russell, [1866] (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/f93f021a-6725-4569-a842-88a377a668a3/Field%206.jpg?w=450&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

Title page, chromolithograph by Robert Dudley, in The Atlantic Telegraph, by William Howard Russell, [1866] (Linda Hall Library)

![Dropping a marker buoy from the Great Eastern, 1865, detail of a chromolithograph by Robert Dudley, in The Atlantic Telegraph, by William Howard Russell, [1866] (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/578195af-0393-4e44-bd9b-6d65001243b9/Field%207.jpg?w=775&h=526&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

Dropping a marker buoy from the Great Eastern, 1865, detail of a chromolithograph by Robert Dudley, in The Atlantic Telegraph, by William Howard Russell, [1866] (Linda Hall Library)

We have several books in our collections that commemorated the cable-laying attempts of 1857-58 and 1865-66 with images. The showier one is The Atlantic Telegraph, by William Howard Russell, illustrated by Robert Dudley, and published in London in 1866. We have already published a post on Russell's book, where you may see five of the beautiful colored lithographs; we display one more here, which was not included in our first post, as well as the illustrated title page (sixth and seventh images). The other book, which has not made an appearance anywhere in this series, is Laying the Atlantic Telegraph Cable from Ship to Shore: A Series of Sketches Drawn on the Spot, by John R. Isaac and printed by him in tinted lithography with explanatory details, published in London, 1857-58. This is slightly smaller in format than Russell's folio, and the lithographs are tinted, not full-colored, but it still has some impressive illustrations (third, fourth, and fifth images). We do not own the allegorical lithograph that we show in our first image; our source is the copy in the Library of Congress. We see the lion of England joined by the Atlantic cable to the eagle of the U.S.; small vignettes depict the termini at Heart's Content and Valentia. Cyrus Field's portrait is at top center.

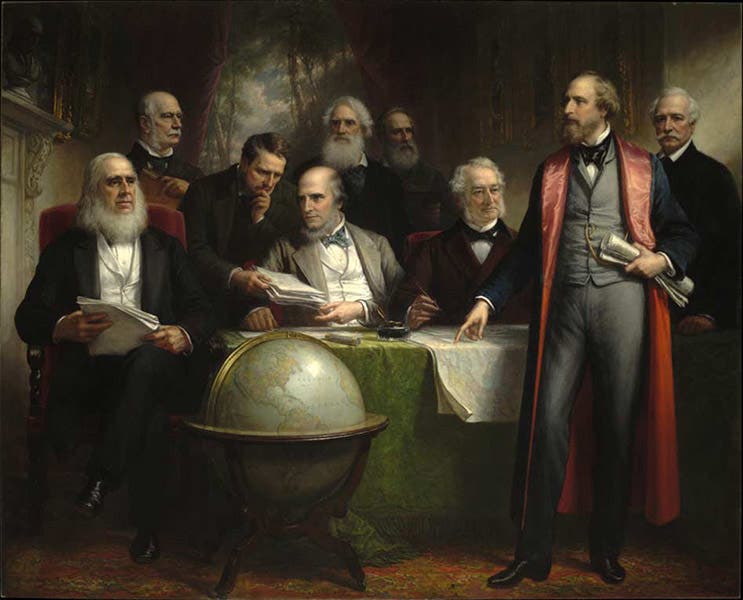

In 1895, a committee of businessmen commissioned a painting of the entrepreneurs behind the Atlantic Cable, and presented it to the New York Chamber of Commerce (eighth image). It is now called The Projectors, although it was referred to at the time as Early Atlantic Cable Men, which I like better. The artist was Daniel Huntington, who included himself at the back. Cyrus Field is standing magisterially at the right; the other major investor, Peter Cooper, with the full white beard, is seated at the far left, and Field's globe, which gave him the inspiration for the cable, is front and center. The globe survives and is now in one of the museums at the Smithsonian Institution. The painting itself has been transferred to the New York State Museum.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Allegorical lithograph, The Eighth Wonder of the World: The Atlantic Cable, Kimmel & Forster, [1866], Library of Congress (loc.gov)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/e59f2e02-efe9-40a6-a0fd-29d8267a4e79/Field%201.jpg?w=534&h=582&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Allegorical lithograph, The Eighth Wonder of the World: The Atlantic Cable, Kimmel & Forster, [1866], Library of Congress (loc.gov)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/e59f2e02-efe9-40a6-a0fd-29d8267a4e79/Field%201.jpg?w=735&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Portrait, imperial salted-paper print by Matthew Brady, [1858] (atlantic-cable.com)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0f15e8cd-6362-4bb0-98e3-b9d145ac0f9e/Field%202.jpg?w=438&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)