Scientist of the Day - Conrad Gessner

Conrad Gessner, a Swiss naturalist, was born Mar. 26, 1516. Gessner was the most distinguished naturalist of the late Renaissance, a contemporary of, but also an inspiration for, Pierre Belon, Guillaume Rondelet, and Ulisse Aldrovandi. He was close to being an armchair naturalist, in that he primarily worked from his study and acquired his knowledge from reading and correspondence, but he was reasonably well acquainted with actual animals and animal specimens.

Gessner is best-known for his monumental Historia animalium, which appeared in four large folio volumes between 1551 and 1558, and was then translated into German and issued all over again in 1563, this time in one fat volume. We have both sets in our history of science collection. Both of our copies have many large hand-colored woodcuts that are as attractive as animal images ever get, and we featured them in a post in 2019, and in our exhibition celebrating the Charles Darwin bicentennial in 2009, The Grandeur of Life.

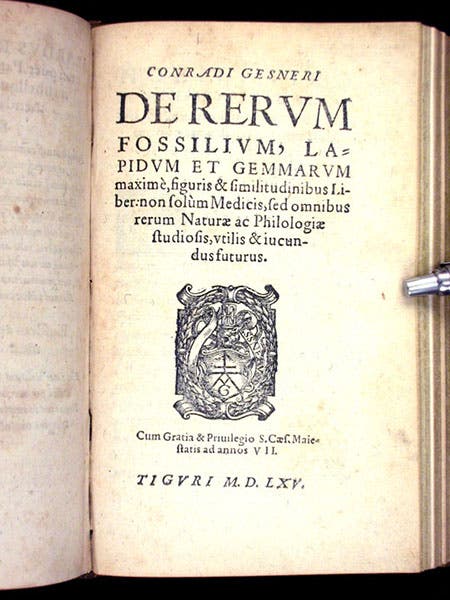

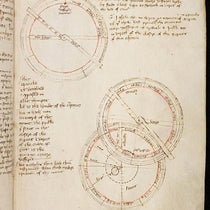

Today we highlight another Gessner work, which, on the outside, is far less imposing than his massive history of animals. It is a collection of 8 treatises on fossils, one of which was written by Gessner, the rest being publications by others, edited by Gessner into a fat octavo fossil reader. But its small size belies its significance. This was the first illustrated book on fossils, including a variety of woodcuts showing the kinds of objects that one would find in a collection like Gessner's.

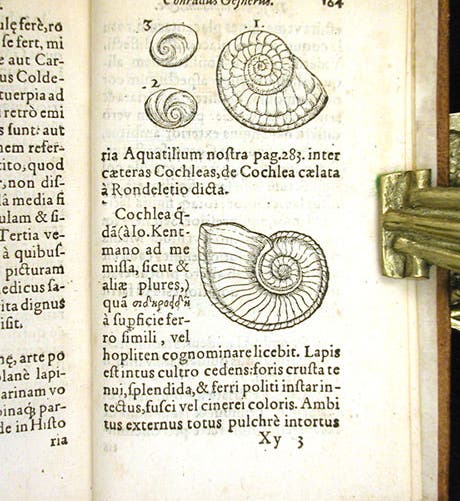

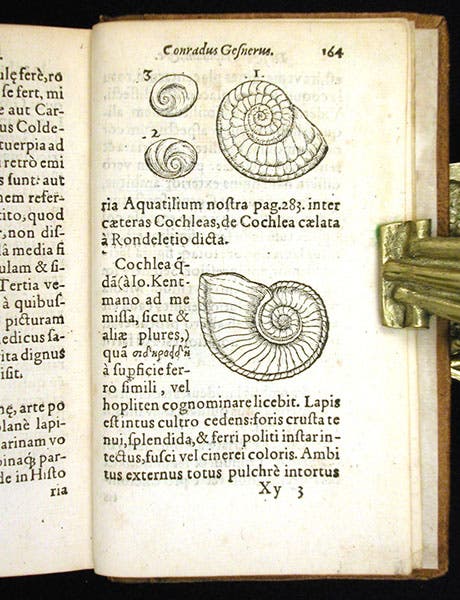

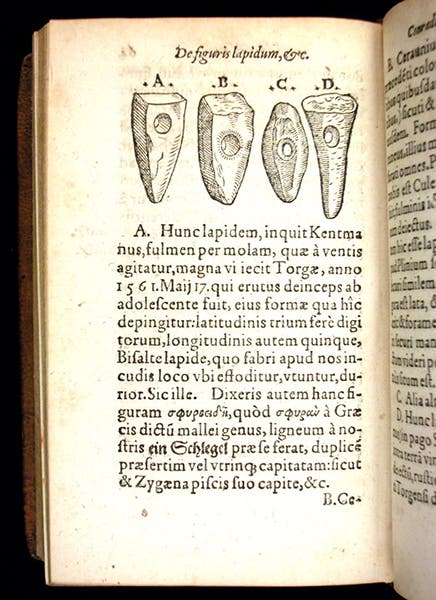

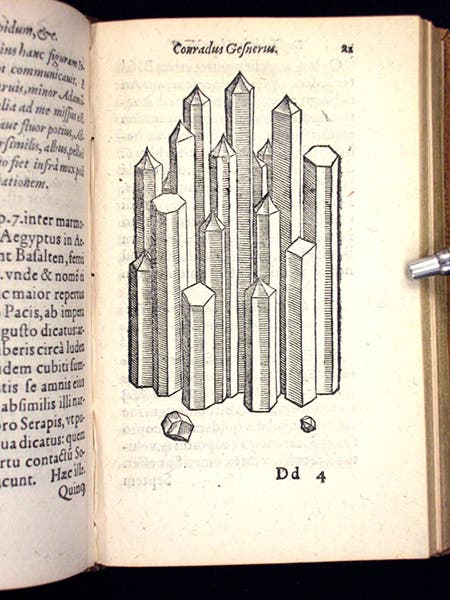

In Gessner's day, fossils were not considered to be the remains of living creatures, but were rather "figured stones" that grew in the earth where you find them. If a stony object had a “shape,” and was not just a rock, then it qualified as a figured stone. This explains why Gesner's collection included objects such as prehistoric stone tools (third image), and basalt prisms (fourth image), which are certainly figured stones, but would not fall into our modern category of fossils.

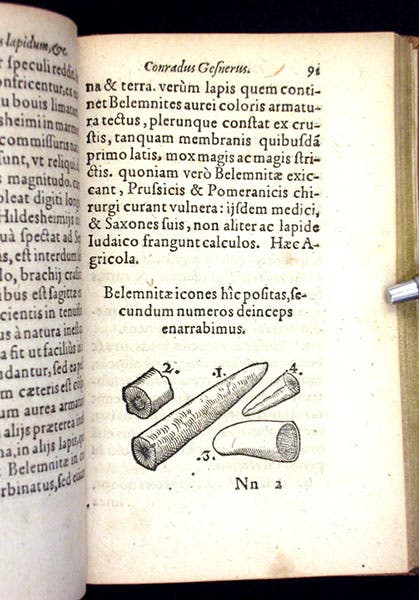

One of the reasons why Renaissance figured stones, even the ones that looked like living things, were not considered to be organic remains, is that often there are no living creatures that exactly resemble the fossils. This would be the case with ammonites (first image), and with belemnites (fifth image). If one were to accept them as organic, then one would have to admit that animals formerly living are now extinct, and most Renaissance naturalists were not ready to accept extinction, since it would imply that species created by God had disappeared from his creation.

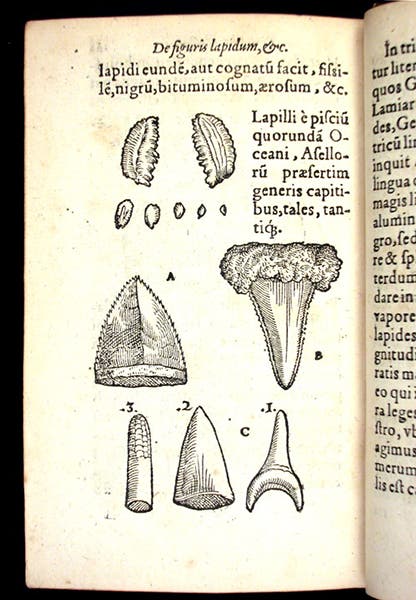

One of Gessner’s woodcuts shows a variety of what were called in Latin, glossopetrae – tonguestones (sixth image). These look like shark’s teeth, but since sharks were not known to frequent the mountains of Switzerland, it must be a resemblance only, or so Gessner thought. One hundred years later, tonguestones would turn out to be crucial fossils, when Nicolaus Steno (1667) demonstrated that tonguestones are indeed sharks' teeth, the remains of once-living organisms, and we should no longer deny the fact, but rather figure out how the remains of sharks became solidified within other rocks and transported to the mountains.

Gessner’s collection of eight treatises has the collective title: De omni rerumm fossilium. The treatise Gessner wrote, the last in the collection, and the one with all the woodcuts, has the individual title: De rerum fossilium. We acquired our copy at the fourth Honeyman sale in 1979.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.