Scientist of the Day - Cloudesley Shovell

Cloudesley Shovell, an English naval officer, was born sometime in November of 1650. He performed well in various naval battles in various wars and rose to become Admiral and commander-in-chief of the Royal Navy. But nothing he did during his life is remembered quite so well as the way his life ended.

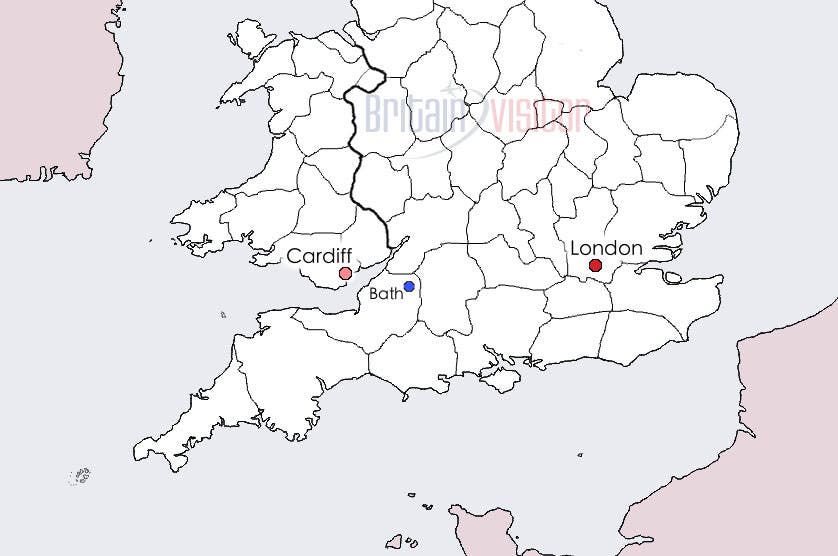

On this day, Oct. 22, 1707, he was returning home with a fleet of 21 ships from engagements in the Mediterranean. The ships had entered the English Channel, but it was a dark and stormy night, and Shovell and his senior staff were trying to figure out exactly where they were. Shovell concluded, or was advised, that they were just west of the coast of Britanny in France. That meant that to reach the port of Plymouth, they would have to sail northwest from their present position. Unfortunately, they were a hundred miles west of Britanny, and northwest of their position were the dangerous rocky shoals of the Isles of Scilly, just off the southwestern tip of Cornwall (see map, third image).

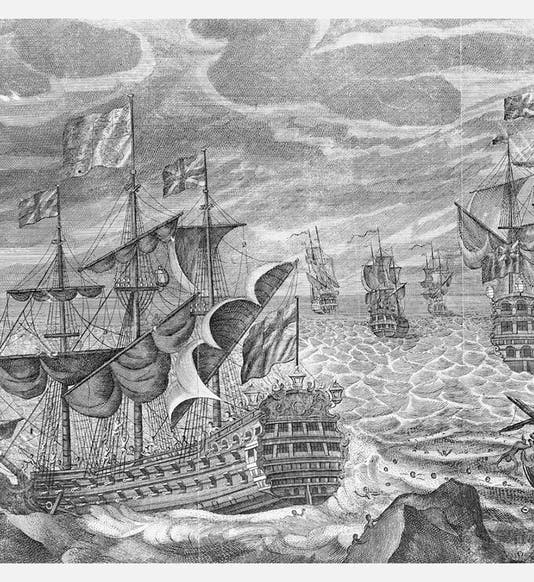

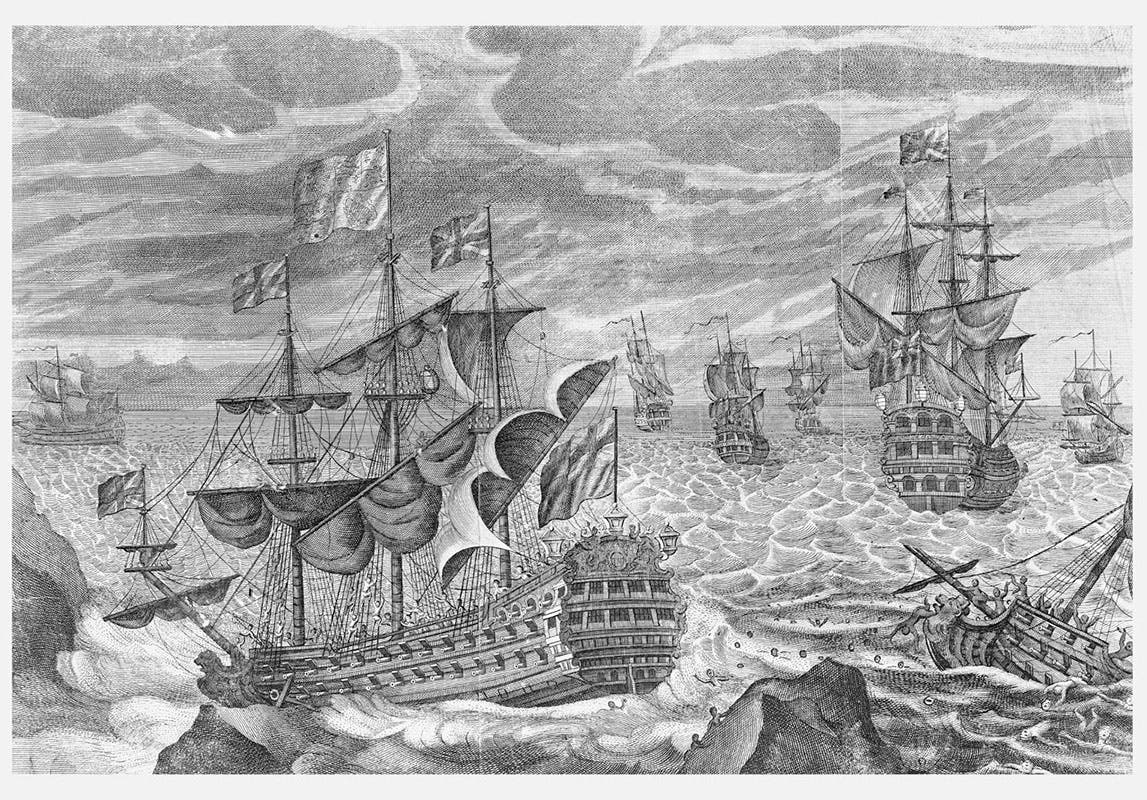

The flagship HMS Association was the first to hit the rocky islands, and it went down in just a matter of minutes. There had been 800 souls on board, and none were saved. The HMS Eagle followed, and then the Romney – both sank immediately, and only one man survived. There were some 1320 men on board the three ships, and all died save one. We include a contemporary artist’s impression of the disaster at Scilly (first image). Several other ships struck the rocks, one more sank, and other lives were lost – no one knows exactly how many, at least 1400 in all, and perhaps as high as 2000. It was one of the worst naval disasters in British history. Sir Cloudesley was one of those who perished. His body washed up on one of the Scilly isles, and he was taken back to London and eventually entombed in Westminster Abbey, under a handsome reclining statue by Grinling Gibbons (fifth image).

It might seem strange to so honor a man whose determination of his fleet's position was in error by a hundred miles, thereby costing the lives of so many sailors. But the truth is, it wasn't Shovell's fault. No one in 1707 had a good way to determine longitude, and although latitude was easier to measure in clear weather, it was very difficult in stormy conditions when the seeing is poor. It had of course been this way forever, and seamen groused and commanders erred and men died, but no one did anything to change the situation. And this is where the Isles of Scilly naval disaster stands out. Both the public and the Admiralty were so aghast at the great loss of lives and ships at Scilly that authorities finally decided that it was high time to solve the "longitude problem". After receiving petitions from merchants and seamen, Parliament in 1714 passed the Longitude Act, which established a Board of Longitude and offered a £20,000 reward to anyone who solved the longitude problem.

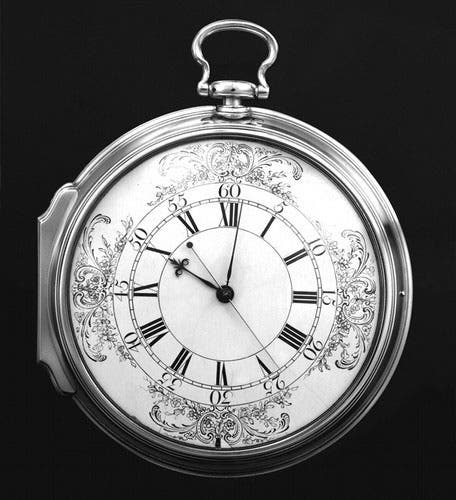

£20,000 was a tidy sum in those days (the equivalent of tens of millions of dollars today) and it stimulated a great deal of ingenious activity, culminating in John Harrison's invention of the marine chronometer in the early 1750s, which allowed one to determine time, and hence longitude, at sea with an error of only a few miles. His masterpiece was H4, a large precision watch that passed its first sea trial in 1761, losing only a few seconds in crossing the Atlantic and giving the longitude of Jamaica within several miles (sixth image). It had to pass another test, and then overcome a great deal of bureaucratic resistance, before Harrison finally received the balance of the payment due him, which everyone now agrees he highly deserved. Disasters at sea caused by errors in determined position became much less frequent thereafter. The Scilly Isles shipwreck was a very sad day in the annals of maritime history, but it just may have saved the lives of countless future sailors.

Not being British, I did not learn about the Scilly naval disaster in grade school. Instead, I had to read about it in Dava Sobel's award-winning book, Longitude (1995), which it just might be time for you to read again, or for the first time, if somehow you missed it when it first came out.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.