Scientist of the Day - Claude-Louis Berthollet

Claude-Louis Berthollet, a French chemist, was born Dec. 9, 1748. Berthollet came from Annecy, in the Savoy region of France, a few miles south of Lake Geneva in Switzerland. He trained as a chemist and physician and came to Paris in 1772, where he became an active member of the chemical revolution then brewing. He teamed up wth Antoine Lavoisier and two others to write a book defining a new chemical language, Méthode de nomenclature chimique (1787; second image). Surprisingly, or perhaps not, he defended the phlogiston theory for quite a while after Lavoisier had given it up, arguing that there were many chemical reactions that were better explained by the phlogiston theory than by Lavoisier’s theory of combustion (which was true). Meanwhile, Berthollet discovered the chemical makeup of ammonia, and learned how to use chlorine compounds for bleaching. Eventually, he did discard the phlogiston theory, although he never did accept another feature of the new chemistry, Joseph Proust’s law of definite proportions.

Berthollet also got along famously with the young Napoleon in the early 1790s, and Napoleon in turn had a great deal of respect for Berthollet. In 1798, Napoleon decided to invade Egypt, seeking a new path to the trade routes of the Indian Ocean, and he planned to take a corps of scientists along to map the country, survey and perhaps plan for a canal to the Gulf of Suez, and learn about Egyptian crafts and trades. To select this corps of scholars, he turned to three French scientific statesmen. Berthollet was one of those three, the other two being Gaspard Monge and Jean-Baptiste Fourier, both mathematicians. Berthollet and his triumvirate not only chose the 150+ savants who would accompany Napoleon, but they joined the expedition themselves, and once the army had successfully taken Cairo, Berthollet, Fourier, and Monge helped established the Institute of Egypt. This institution would direct the scientific exploration of Egypt and collate its findings, and in the process discover the ruins of ancient pharaonic Egypt.

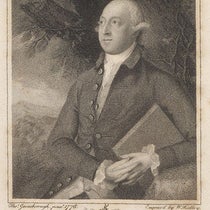

Berthollet had an Egyptian scientific project of his own. He was interested in what were called the Natron Lakes, in the Egyptian desert west of Cairo. In a map of the Nile delta (third image), published later in the Description de l’Egypte (1809-28), Cairo is at the bottom apex of the delta, and the “Lacs de Natroun” are quite a ways up that long depression that runs west-northwest of Cairo. Natron, more formally known as hydrated sodium carbonate, was used by the ancient Egyptians for embalming and glass-making. Berthollet found that nature’s way of making natron is just the reverse of what chemists were accustomed to doing in the laboratory. This was one of the first discoveries anywhere of a reversible chemical reaction. We explained this in a little more detail in the section on Berthollet in our 2007 exhibition, Napoleon and the Scientific Expedition to Egypt. The same volume of the Description contains an aquatint portrait of Berthollet this is quite arresting, based as it was on a painting by the American artist Rembrandt Peale. We show it here as our first image.

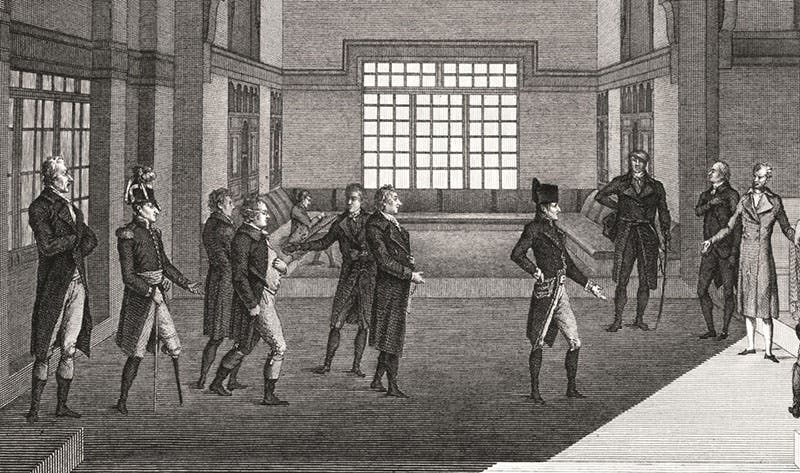

Another portrayal of Berthollet is not very well known, and because it is rarely reproduced, we include a detail of it here (fourth image). It shows the first meeting of the Institute of Egypt on Aug. 23, 1798, based on a drawing by Jean Protain. Napoleon is unmistakable, striding forward at right-center, and Berthollet is the individual just behind him. If would like to identify the other figures, you may consult this webpage of our exhibition catalogue.

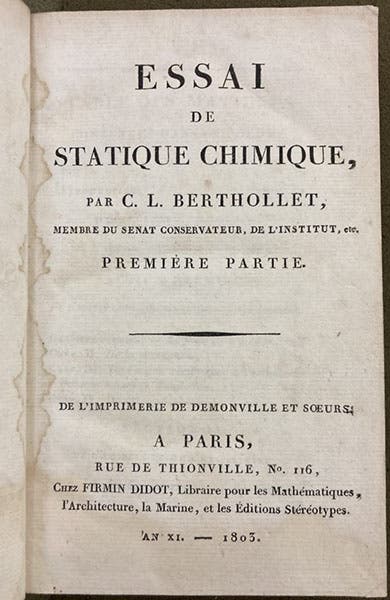

Berthollet's stay in Egypt was short; when Napoleon snuck away in 1799 to return to France and declare himself Consul, he took Berthollet with him, which gave Berthollet the chance to write up his results before the others even got back. One of the first books he produced was Essai de statique chimique, in two volumes, published in 1803. We have this, his most influential work, in its original French edition and in an English translation of the next year.

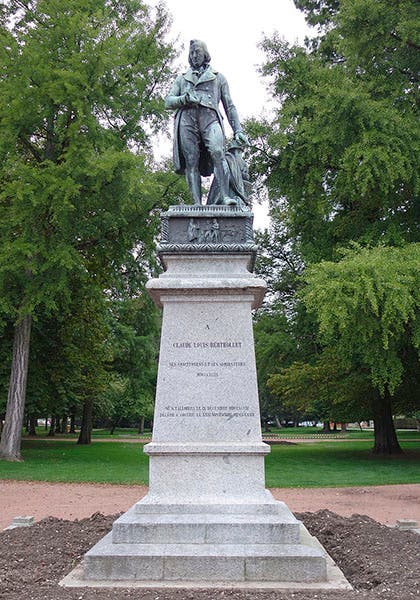

Berthollet lived until 1822, and at the time of his death, he was one of France’s most respected chemists, although he would always be in the shadow of Lavoisier – that is the lot of all French chemists. There is a splendid statue of Berthollet in a picturesque setting on the shore of Lake Annecy in the Upper Savoy (sixth image). Not all statues have to be in city squares.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.