Scientist of the Day - Christoph Scheiner

Christoph Scheiner, a German Jesuit astronomer, died July 18, 1650, just shy of his 77th birthday. Scheiner was one of four co-discoverers of sunspots, which he first observed with his telescope in the fall of 1611. Other early observers were Thomas Harriot, who made a drawing of sunspots on Dec. 8, 1610; Johannes Fabricius, who observed sunspots in the spring of 1611 and was the first to publish about them; and Galileo Galilei, who saw sunspots in the spring of 1611 but didn't begin to study them himself until February, 1612. Scheiner did not know about Harriot or Fabricius, so he thought he might have priority in discovery, and he tried to establish that by writing three letters in rapid-fire order to Marc Welser, a wealthy patron of Augsburg, hoping (and urging) that Welser would publish them and secure Scheiner's priority.

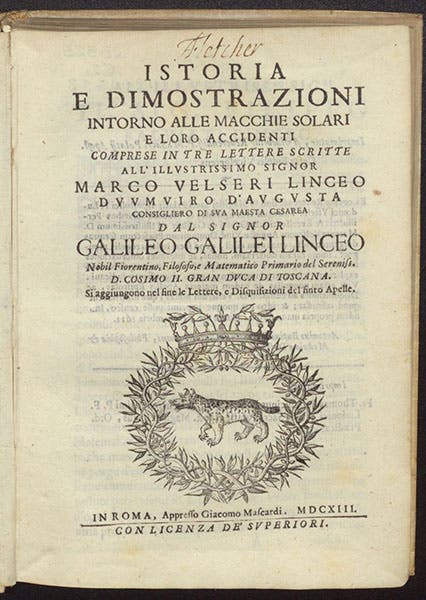

Welser obliged by publishing Tres epistolae de maculis solaribus (Three letters on solar spots) in January of 1612. Scheiner wrote three more letters even before the first three appeared in print, and they were published six months later as De maculis solarib. ... accuratior disquisitio (A more accurate account of solar spots). Next year, Galileo published him own treatise on sunspots, also in the form of letters to Welser, which was called Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari (History and demonstrations concerning sunspots, 1613).

We do not have the 1612 first edition of Scheiner's Tres epistolae, but we do have a fine copy of his second treatise, Accuratior disquisitio (1612; fifth image). We also have a lovely copy of Galileo's Istoria e dimostrazioni (1613), and Galileo just happened to include a reprinting of Scheiner’s first three letters at the end of his own book. So, one way or another, we have the complete set, with one being a second printing, which allows us to ask the question, how did Scheiner and Galileo differ in their portrayal and explanation of sunspots?

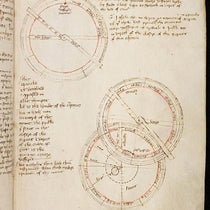

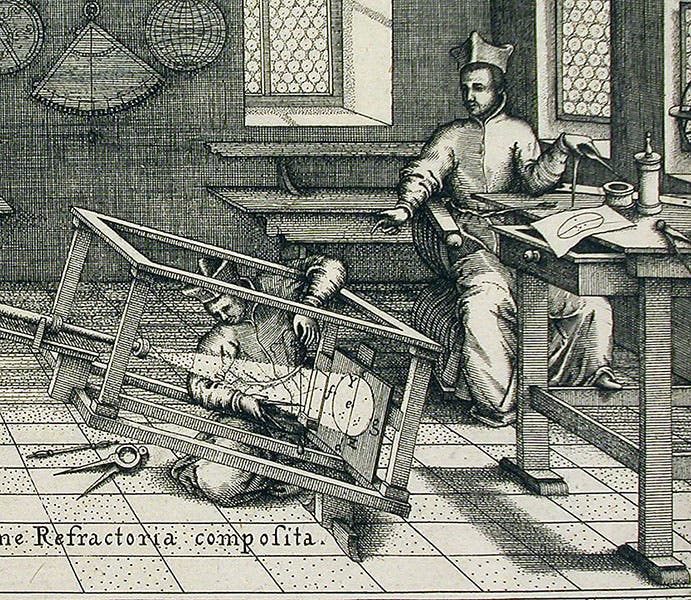

Scheiner spent much of his first treatise defending the idea that sunspots are real objects, and not some spurious entities produced by the telescope, or our eye, or the earth's atmosphere. Being a good Jesuit, he subscribed to the Aristotelian notion that heavenly bodies are perfect and could not possibly have blemishes like dark sunspots. So he proposed that the spots were caused by many small bodies orbiting the sun and casting shadows on the Sun. Sunspots move regularly across the surface of the Sun but change their shapes continually and irregularly, and Scheiner thought that aggregations of orbiting bodies could account for that. Since this was an unorthodox idea, he published his treatise anonymously, taking the name of Apelles, the ancient Greek painter, and signing both treatises "Apelles latens post tabulam" – “Apelles hiding behind the picture" – as Apelles supposedly did, fishing for compliments or criticisms from passers-by (sixth image).

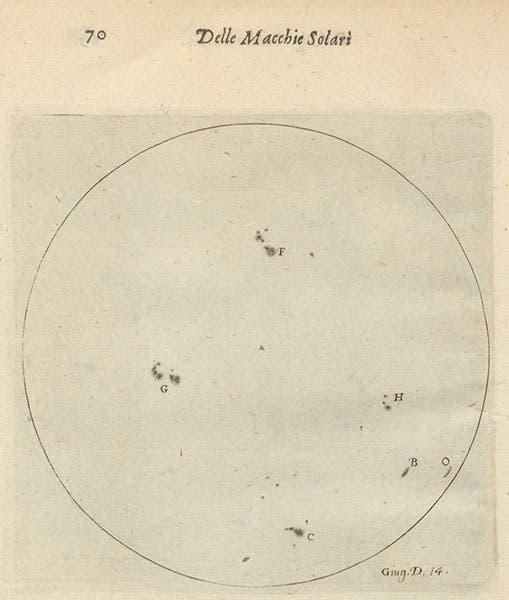

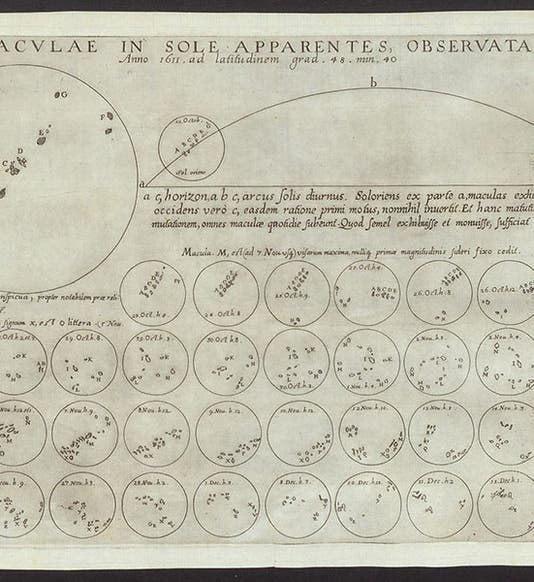

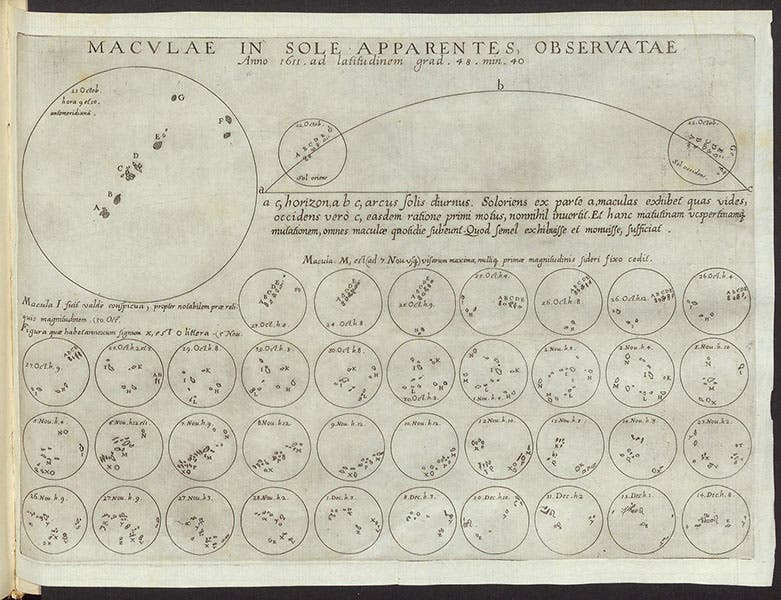

As for using images to demonstrate his observations or support his arguments, Scheiner does not seem to have been a visual thinker. In Tres epistolae, there are three engraved plates, and one of them has a large and promising diagram of how the Sun appeared on Oct. 21, 1611, with another diagram on the plate that shows how the orientations of the spots change as the Sun moves across the sky (first image). But the other daily drawings are tiny, and contain little information, and Scheiner even says that he had to enlarge the spots on the small Suns or else we wouldn't be able to see them at all. The images in Accuratior disquisitio are no better. They were well engraved – Welser chose Alexander Mair, who engraved the star maps in Johann Bayer’s Uranometria nine years earlier, to engrave Scheiner’s plates – but there was just not much information there to put on the plates.

Galileo took quite a different approach in his Istoria e dimonstrazioni. Since he was writing after Scheiner, he could refer to the work of the "masked Apelles," as Galileo called him, and he did so frequently, wittily, and scathingly. Galileo spent no time at all trying to prove that sunspots are really there – he took it for granted that the telescope did not lie – and spent his time explaining just how sunspots move. He argued that they must be on or just above the surface of the Sun, because they foreshorten as they near the solar limb. The fact that the Sun might be blemished did not bother him at all – after all, two years earlier, he had shown that the Moon has mountains, valleys, and seas.

The most novel feature of Galileo’s Istoria is the way he used images. Galileo, like Scheiner, had written his book as a series of letters to Welser, but he had no intention of letting Welser publish them. Instead, he turned to Federico Cesi, patron of the Accademia dei Lincei (Academy of the Lynx), which Galilel had been invited to join in 1611. Cesi found a skilled engraver, Mattheus Greuter, and instead of putting a month of observations on a single plate, Galileo devoted each plate to a single day, so the outline of the Sun is large on each, and the details of the sunspots are easily visible (eighth image). He put all the plates together, in order by the day of observation, so one can easily see how the pattern of sunspots changes as the days go by. If you go to our online copy and move to page 65 of the pdf, you can flip through all 24 engravings in succession.

Scheiner did not take kindly to his abuse at the hands of the Florentine, and he and Galileo were now enemies for life. Scheiner kept studying sunspots, and in 1626, he began publishing a much larger folio on the Sun, his Rosa Ursiina (1626-30). This work has an elaborate emblematic frontispiece which shows that Scheiner had finally learned the value of visual argument, as he iconographically considered the relative value of Reason, Scripture, Ancient Authority, and the Senses in trying to determine the nature of sunspots. We discussed this frontispiece six years ago in our first post on Scheiner. Our portrait here (second image) is a detail of a plate from that post.

I was greatly assisted in writing this post by two articles: “Galileo and Scheiner on sunspots: A case study in the visual language of astronomy”, by Albert Van Helden, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 1996, 140:358-96, and “Mere projections: Sunspots and the camera obscura,” by Eileen Reeves, Galilaeana, 2007, 4:47-77.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Title page, Tres epistolae de maculis solaribus, by [Christoph Scheiner], in Galileo Galilei, Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari, 1613 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a9594259-f22c-4c9c-9c57-b23e0adcb30e/scheiner3.jpg?w=432&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Sunspots observed and drawn in December 1611, and January, 1612, engraving by Alexander Mair, in [Christoph Scheiner], Tres epistolae de maculis solaribus, in Galileo Galilei, Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari, 1613 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/fc3af998-276e-4592-8f22-bc3e297a55b9/scheiner4.jpg?w=426&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Title page, De maculis solarib. ... accuratior disquisitio, by [Christoph Scheiner], 1612 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/49b888f7-a0ba-4945-9960-46bdf4a86814/scheiner5.jpg?w=444&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![Signature of “Apelles hiding behind the picture," De maculis solarib. ... accuratior disquisitio, by [Christoph Scheiner], 1612 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/77b57be9-5fed-4b55-bf5c-33fec10132f9/scheiner6.jpg?w=716&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)