Scientist of the Day - Chicago Pile 1 (CP-1)

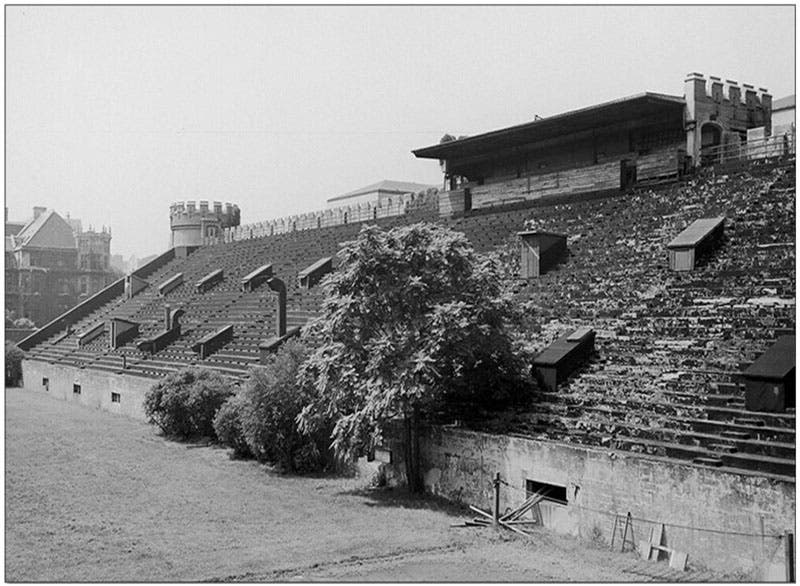

Exactly 80 years ago today, on Dec. 2, 1942, at precisely 3:25 PM, the final control rod was removed from a pile of graphite blocks laced with uranium, hidden beneath the stands of old Stagg Field at the University of Chicago, and the world’s first man-made, self-sustained nuclear reaction began. The stack of bricks was called Chicago Pile 1, CP-1 for short, and it was the handiwork of a team headed by Italian emigre Enrico Fermi, working for Arthur Compton on a project with the code name Met Lab, one of the earliest phases of the Manhattan Project. Although a self-sustaining nuclear reaction seemed possible on paper, this was the first attempt to put theory into practice.

The idea is simple, once you know that uranium is fissionable, which was discovered by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in 1938. Uranium is radioactive and emits neutrons. If a slow neutron strikes another uranium nucleus, it will cause the atom to split and emit more neutrons, thus causing a chain reaction. Most neutrons emitted by uranium are fast neutrons, which are not easily absorbed by other atoms, so one needs to slow them down to achieve a self-sustaining reaction, and pure graphite does this nicely. To prevent a runaway reaction, you need something that mops up neutrons, and this can be done with cadmium control rods.

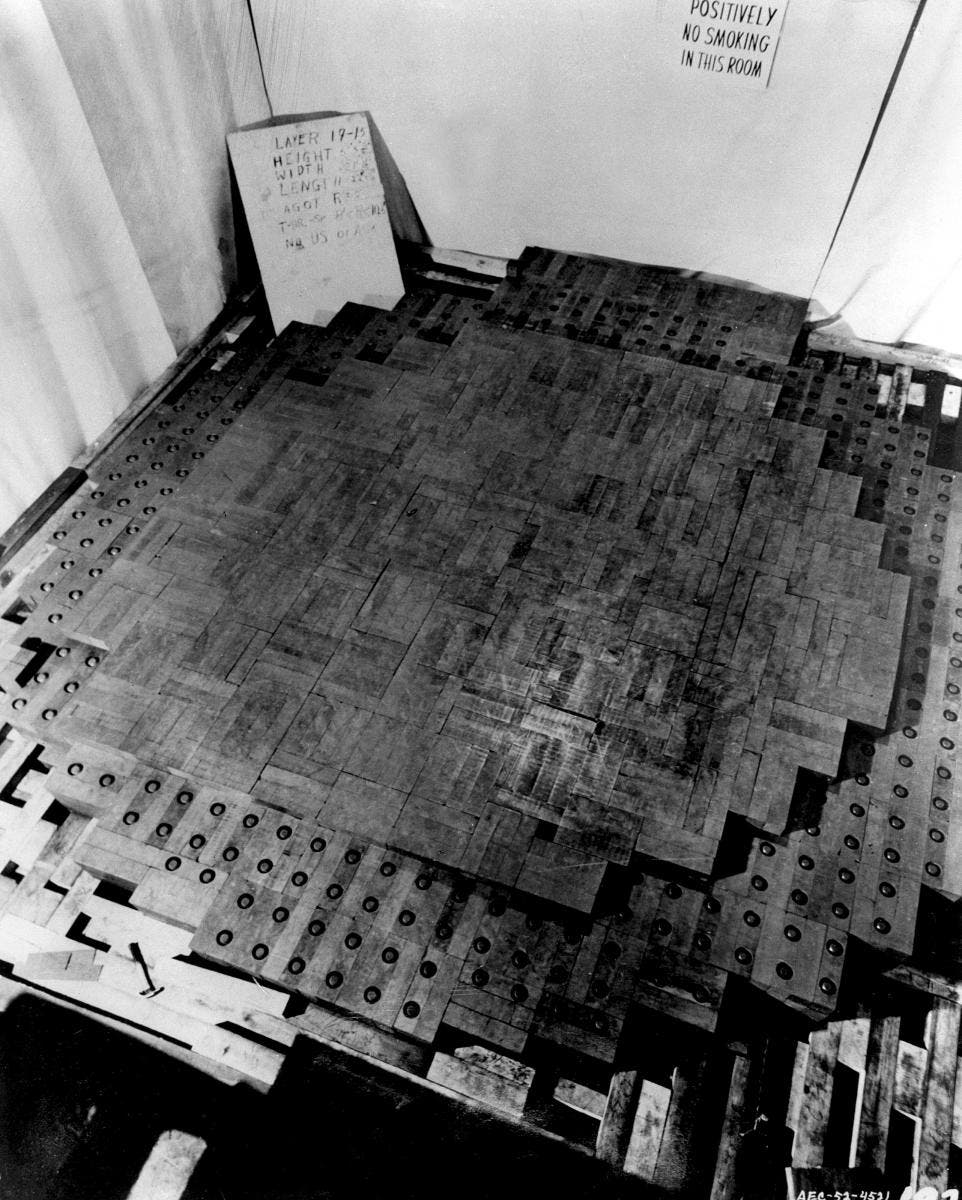

CP-1 was constructed of 57 layers of graphite bricks. Some of the layers had holes bored in the bricks to hold uranium pellets; these were sandwiched between graphic layers without uranium. In addition, holes were bored through the layers for cadmium control rods; the rods could be raised or lowered to fine-tune the reaction. It was quite a project to produce and stack the approximately 45,000 pure graphite bricks and insert the pellets, which were both uranium metal and uranium dioxide. But it all worked as Fermi and Leo Szilard had calculated it would. This meant that further reactors could be built to produce plutonium, the next element up from uranium, which would be the fissionable material used in all the atomic weapons later constructed save one.

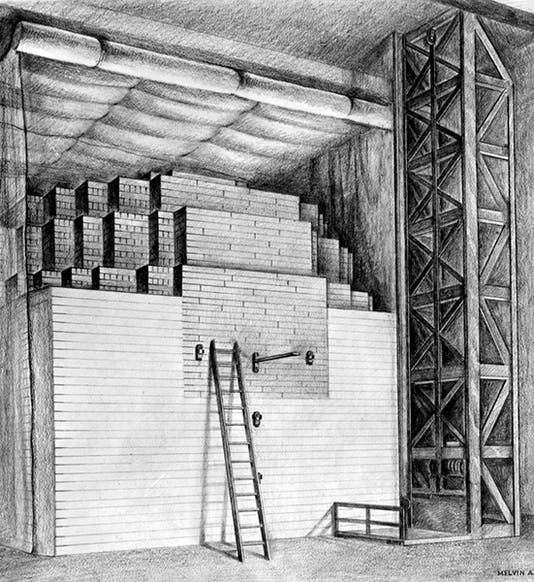

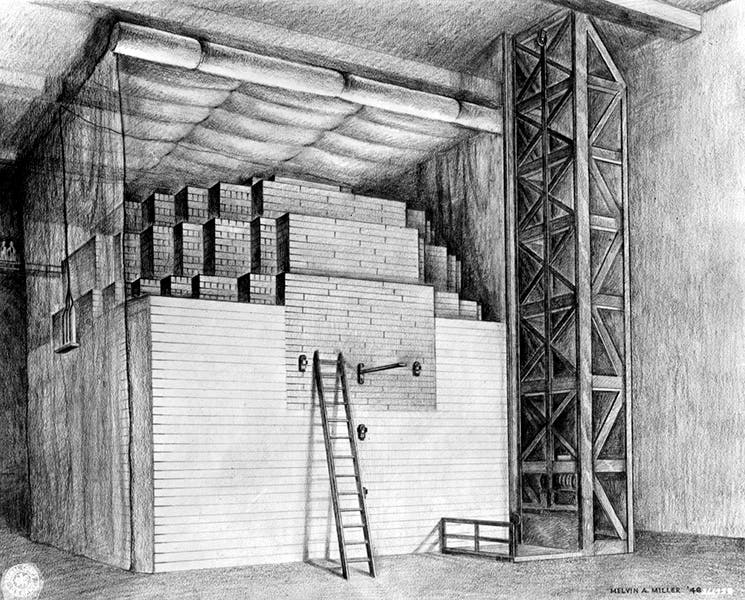

So far as I can determine, no photographs were taken of CP-1, for security reasons. So what we have for documentary purposes are several drawings. The best of these was one drawn by Melvin Miller that shows the completed stack of graphite bricks (first image). There are also some photographs that show the layering of the pile, and these are often captioned as if they show the actual building of CP-1, but as I understand it, these depict a re-enactment, possibly when the pile was dissembled in 1943 and moved to the new Argonne National Laboratory outside Chicago. Still, they are useful in allowing us to see the alternating of the uranium-containing layers with the all-graphite layers (third image).

When the pile went critical on Dec. 2, 1942, Compton called his boss, James Conant, to tell him of the successful reaction, but he realized they had prepared no code for the occasion. So he improvised, and told Conant "the Italian navigator has landed in the New World." "How were the natives?" asked Conant. Compton replied: "very friendly".

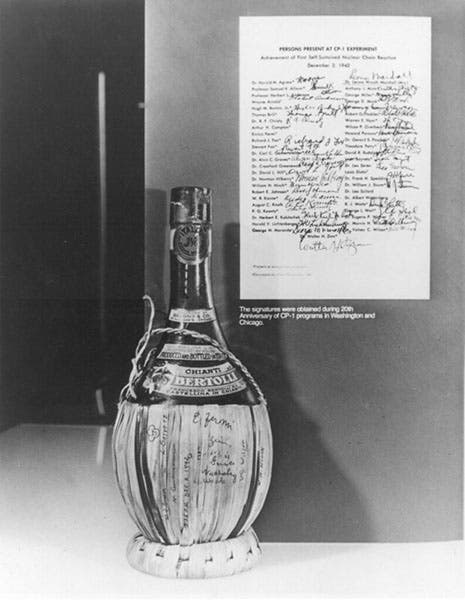

The 49 people present under the bleachers that day celebrated with sips of chianti from a raffia-wrapped bottle brought for the occasion, and when the bottle was empty (as it was very quickly), they each signed the raffia with their names. That bottle still survives somewhere, as there are pictures of it on the University of Chicago and Argonne National Laboratory websites (fifth image). The signatures were later transcribed to a single sheet of paper, which you can see in the photograph. You can view a readable version of the signature sheet at our post on Leona Woods, the only woman in attendance that day.

After the war was over, the CP-1 staff held a reunion at the University of Chicago on Dec. 2, 1946, where a photograph was taken (second image). Fermi is at the far left of the front row; Leo Szilard wears the rumpled trench coat in the second row on the right; he stands next to Leona Woods. Arthur Compton was not present. We published a post on Fermi six years ago, but we discussed there his work of the 1930s on discovering the importance of slowing neutrons for nuclear reactions, and did not talk about Chicago Pile 1. The post also shows the engaging Fermi bust that we have here at the Library, sculpted by Robert Berks. We have also published a post on Szilard, with some mention and an image of CP-1, different from the one we show here (first image).

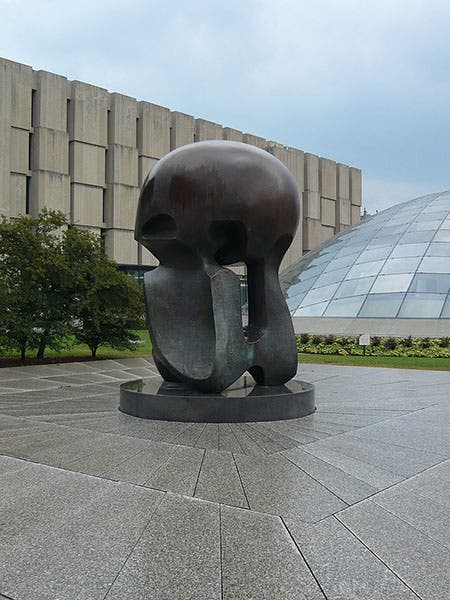

Since we are so proud of the wonderful Henry Moore sculptures on the grounds of the Nelson Atkins Museum here in Kansas City, we might point out that the city of Chicago commissioned a Moore sculpture, called “Nuclear Energy,” which sits on the exact site of the first atomic pile (Stagg Field was torn down in 1957). The Moore sculpture was unveiled on Dec. 2, 1967, at 3:25 PM, exactly 25 years after CP-1 achieved criticality (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)