Scientist of the Day - Chester Stock

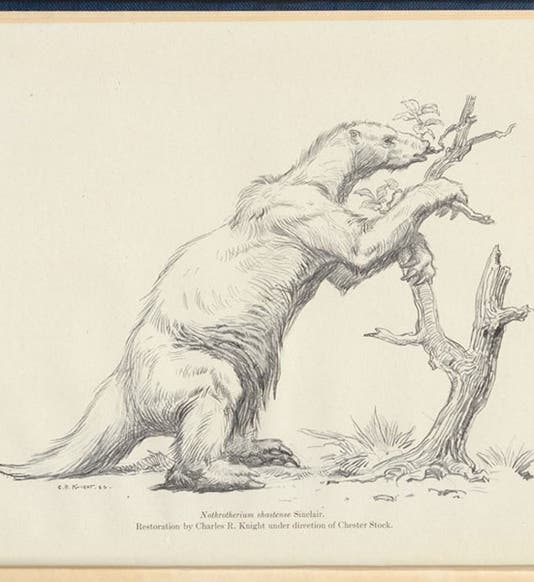

Chester Stock, an American paleontologist, died Dec. 7, 1950, at age 58. Stock studied vertebrate fossils at the University of California in Berkeley. His major work was a study of the large ground sloths (edentates) that inhabited Southern California in the late Pleistocene. It had the lively title: Cenozoic Gravigrade Edentates of Western North America, and it was published by the Carnegie Foundation in 1925. We have a copy in our collections. The most attractive feature of the book is a frontispiece by Charles Knight, reconstructing on paper what Stock called a Nothrotherium shastense and we now refer to as a Nothrotheriops shastensis, a medium-sized ground sloth.

Most of the ground sloth specimens that Stock studied were dug out of the Rancho La Brea tar pits in downtown Los Angeles. These tar pits (asphalt seeps would be a better term) were discovered in the 19th century but were mainly viewed as indicators of the presence of underground oil (note the oil derricks in the background of a 1910 photo of one of the seeps, fourth image, below).

It was not until around 1906 that anyone realized how fossil-rich these pits were. The Los Angeles County Museum was given a window of two years to dig out all the fossils they wanted by the then owner of the site, a man named Alan Hancock, and hundreds of thousands of bones and skulls of dire wolves, saber-tooth cats, and ground sloths were excavated between 1913 and 1915 and stored in a large basement room at the Museum. Hancock then gave the site to Los Angeles County, which established a preserve, Hancock Park, that contains many of the pits, and eventually an on-site museum, the George C. Page Museum, that now houses most of the fossils dug up at Rancho La Brea. Stock, meanwhile, was chosen in 1926 to start up the Department of Geology at Caltech in Pasadena, and eventually he became chief curator of geology at the Los Angeles County Museum (now the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County). By the time of his death, Stork was recognized as one of the world’s premiere authorities on the Pleistocene mammals of North America.

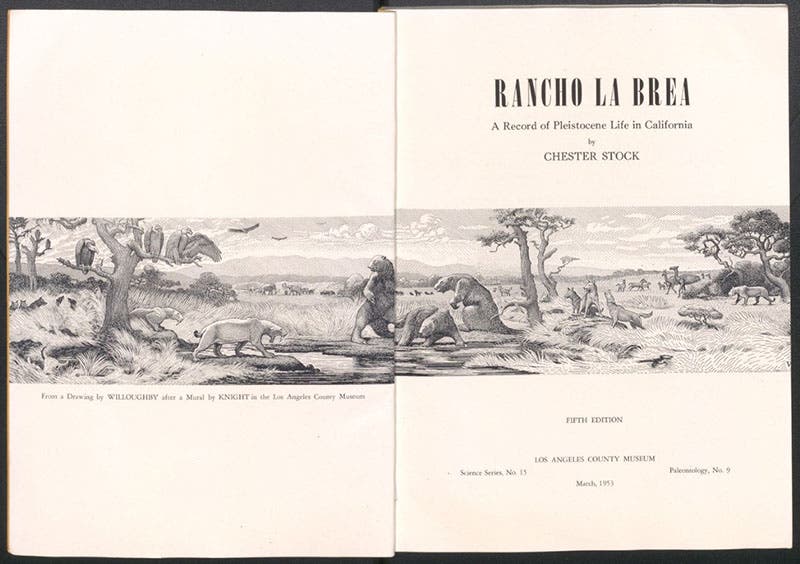

Title page and facing page, reproducing a drawing of a mural by Charles Knight, in Chester Stock, Rancho La Brea: A Record of Pleistocene Life in California, 5th ed., 1953 (author’s copy)

In 1930, Stock published a guide to the animals of the tar pits, called Rancho La Brea: A Record of Pleistocene Life in California. It has been an indispensable source since its publication and has never gone out of print. I own the 5th edition, published in 1953, and I expected the Library to have the first (1930) edition, and was surprised to discover that we have no edition at all in our collections. I hope we can find one on the market and add it to our holdings. I include several images here from my copy, most notably the title page and facing page (fifth image), which reproduces a drawing made after a mural by Charles Knight for the Los Angeles County Museum, depicting the saber-tooth cats, ground sloths, camelids, and dire wolves that inhabited the area of the tar pits 15,000 years ago.

Fossils in situ in Hancock Park, including skull of dire wolf aet top amid hip bones of a ground sloth, photograph, undated, in Chester Stock, Rancho La Brea: A Record of Pleistocene Life in California, 5th ed., 1953 (author’s copy)

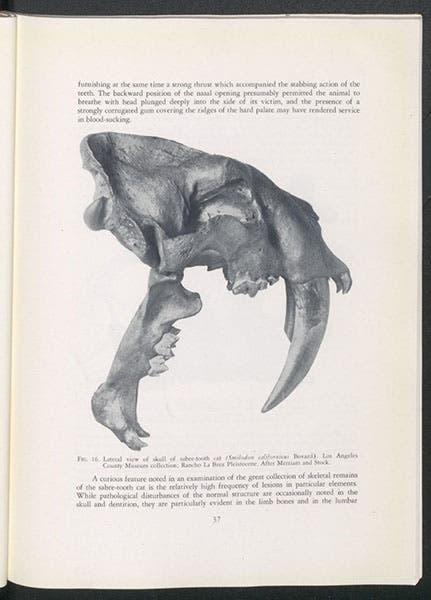

Skull and jaw of Smilodon, a saber-toothed cat from the tar pits, in Chester Stock, Rancho La Brea: A Record of Pleistocene Life in California, 5th ed., 1953 (author’s copy)

The George C. Page Museum, which preserves Stock’s specimens, is a very popular tourist destination, sitting as it does right there on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. Here is a photograph of the front of the museum. If any of you are fans of Martin McDonagh’s film Seven Psychopaths, I might point out that the early scene where psychopath no. 1 (and no. 7), played by Sam Rockwell, steals a dog in order to return it later to its owner for a reward, is none other than the plaza in front of the Page Museum. If you look carefully, at the beginning of the scene, you can see a (concrete) mastodon in the background, struggling against the (simulated) asphalt’s inexorable pull.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.