Scientist of the Day - Charles Willson Peale

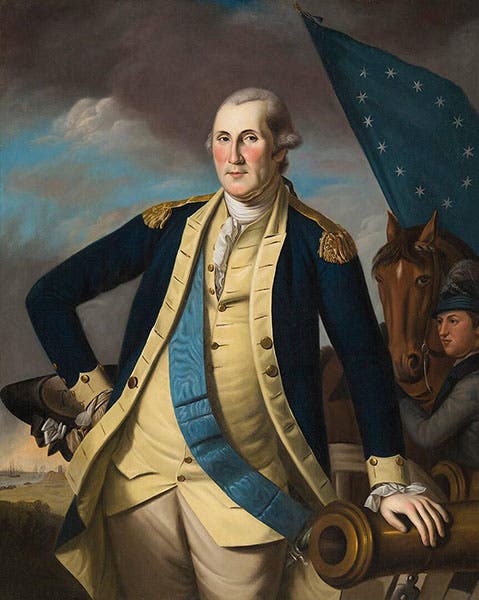

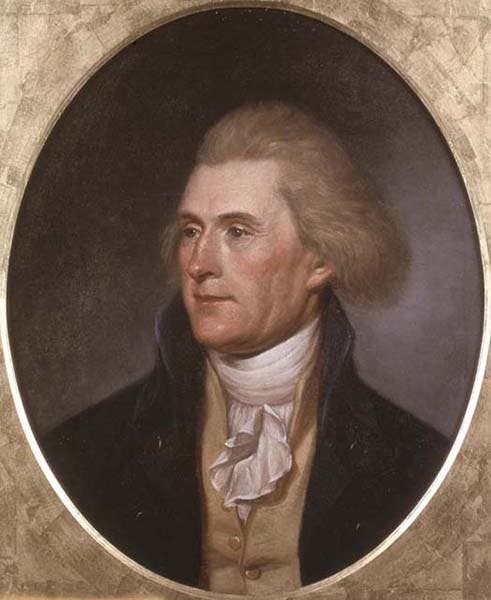

Charles Willson Peale, an American painter and collector of naturalia, was born Apr. 15, 1741, in colonial Maryland. Around 1776, he moved to Philadelphia and set up a studio, where he painted portraits of, among others, George Washington (second image) and Thomas Jefferson (third image). But he also collected natural objects, and in 1786, he opened a museum, Peale’s Museum, on Independence Square in Philadelphia. It was the first public museum in the United States. In 1801, he recovered mastodon bones in a marl bog in southeast New York, put together a skeleton, and erected it in his museum. Among his three wives, he sired 16 children, whom he gave names like Rembrandt, Rubens, Charles Linnaeus, and Sybilla Miriam; four of the sons went on to become distinguished painters in their own right. Six years ago, we attempted to tell the story of all this in a single post. We bit off far more than we could chew. So we are going to start over and break Peale's career down into three separate posts over the next few months. We will leave the old post in place until we are done, and then we shall gently remove it.

In this post we are going to discuss Peale’s Museum. It had an odd origin. Peale started out as a portrait painter in 1776, a profession at which he excelled. His first four children, Raphaelle, Rembrandt, Titian I, and Rubens were born during this period. Around 1784, Charles Peale decided he wanted to open a gallery in Philadelphia for his portraits, where he could charge admission and provide some secure income for his growing family. About that same time, he was asked to draw some elephant-like bones that had been dug up at Big Bone Lick in Kentucky. He had them strewn around his studio when he was visited by a friend, who was most intrigued. He told Peale that he would much rather travel some distance and pay a fee to see artifacts like these, rather than view a bunch of portraits. Peale apparently rethought his gallery plans and decided to open a natural history museum. One should note that he knew nothing about natural history, taxonomy, taxidermy, or museums – indeed it is thought that he had never even been to a museum until 1786, when he opened his own on Independence Square in Philadelphia. Peale's Museum was the first public museum in the United States.

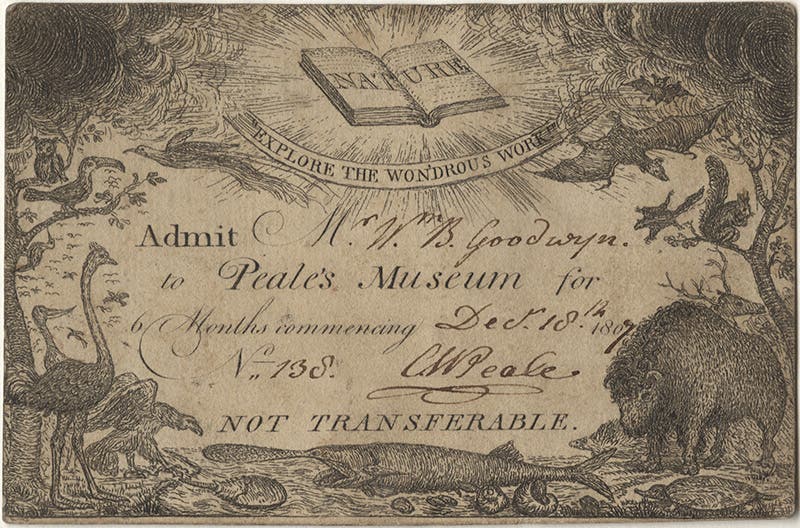

Peale started out collecting birds. He learned to stuff them, discovering that arsenic was a good preservative. At first, he did not know how to arrange or classify them. His only guide was the multi-volume Natural History of Georges Buffon, and Buffon detested taxonomy. But gradually Peale became aware of the Linnaean system of classification, and he eventually adopted it and Linnaeus's binomial nomenclature for his museum, the first to do so anywhere. He printed up emblematic admission tickets, many of which survive (fourth image, below). A sign above Peale's Museum said: "School of Wisdom," and below was another: "The Book of Nature open – explore the wondrous work and institute of laws eternal." Peale's "book of nature opened" appeared as a vignette on the museum tickets. People came and paid their money. One must remember than in 1790, Philadelphia was the largest city in the United States and its cultural center, so there was a ready audience for a museum, if it could be made attractive. Peale’s Museum was just that.

The collections grew and grew, eventually numbering several hundred mammals, an even large number of birds, a variety of snakes and reptiles, and thousands of insects. And, of course, the portraits. When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark returned from their journey west in 1806, Thomas Jefferson ordered that their specimens should go into Peale’s Museum. The same thing later happened with the collections brought back by Zebulon Pike and Stephen Long. When Alexander Wilson was writing his 9-volume American Ornithology, he based it primarily on the birds in Peale’s museum. Before there was a Smithsonian institution, the Peale Museum was America’s museum. And Peale did it all on his own (with considerable help from his sons and daughters), without any assistance from city, state, or the federal government, although he often asked for their support, and was turned down. After Peale’s death, the museum was broken up in the 1840s, and nearly all of the specimens were lost, which is something of a national tragedy.

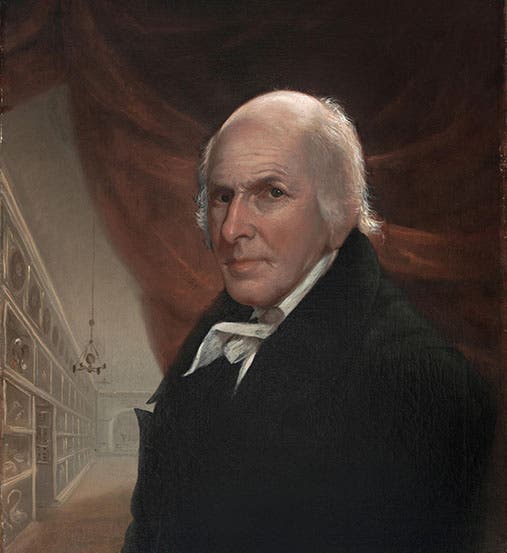

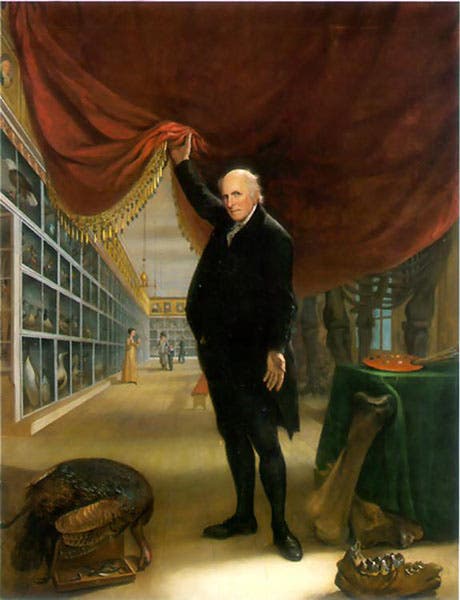

When the Museum was in Independence Hall in Philadelphia, most of the collection was displayed in the “Long Room,” which was sketched by Charles and son Titian Ramsay in 1822. The sketch survives in the Detroit Institute of Art (fifth image, above). It must have been quite something to walk down that hall. The specimens were in niches, often decorated by Peale or his children. The portraits were arrayed at the top. A view of the Long Room can also be seen in our first image, one of Peale’s 1822 self-portraits.

Another self-portrait from that same year shows a full-length Charles, with the Long Room as background, and a curtain about to be lifted on a new addition, the Peale Mastodon (sixth image, above). The “Exhumation of the Mastodon” will be the subject of our second new post on Peale, coming sometime soon.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.