Scientist of the Day - Charles Wilkes

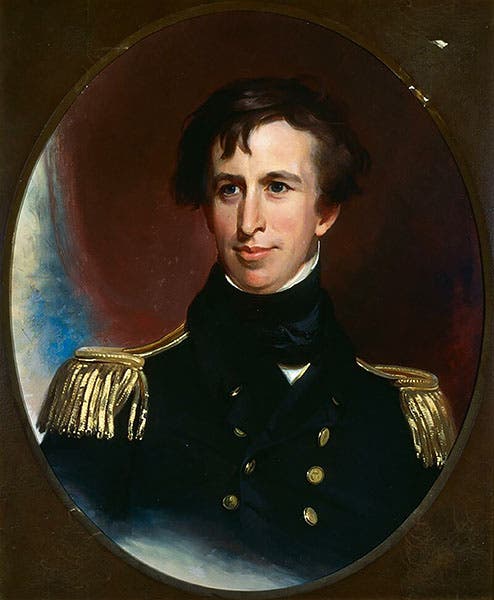

Charles Wilkes, an American naval officer, was born Apr. 3, 1798. In 1838, the United States launched its first national voyage of exploration, inspired by the success of the two latest French voyages of the Astrolabe. The mission was to explore the Pacific, search for a southern continent, and make a side trip up the coast of the Pacific Northwest. The inclusion of civilian scientists was a statement that this was to be a voyage to gain knowledge, not power or land. Naval authorities had problems finding a commander for the five-ship squadron, and settled on young Wilkes, who was eager to go, but who was just a lieutenant at the time.

The ships departed for South America in 1838, and would return in 1842. We wrote a post on Wilkes on this day nine years ago, in which we described Wilkes’ tempestuous relationship with the nine scientists on board (Wilkes did not like civilians on naval vessels), and displayed five plates from the resulting narrative by Wilkes, from the first two volumes, which focused on the trip around Cape Horn and the search for Antarctica.

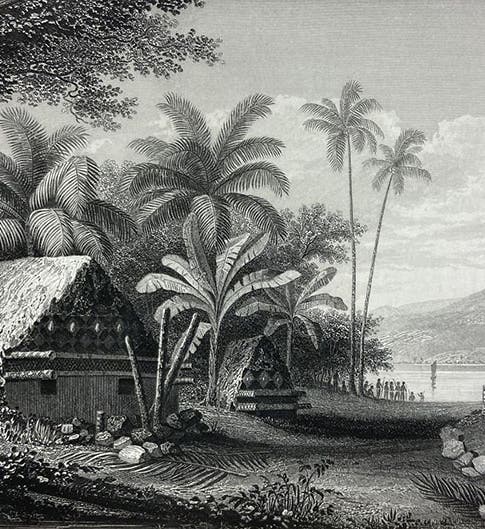

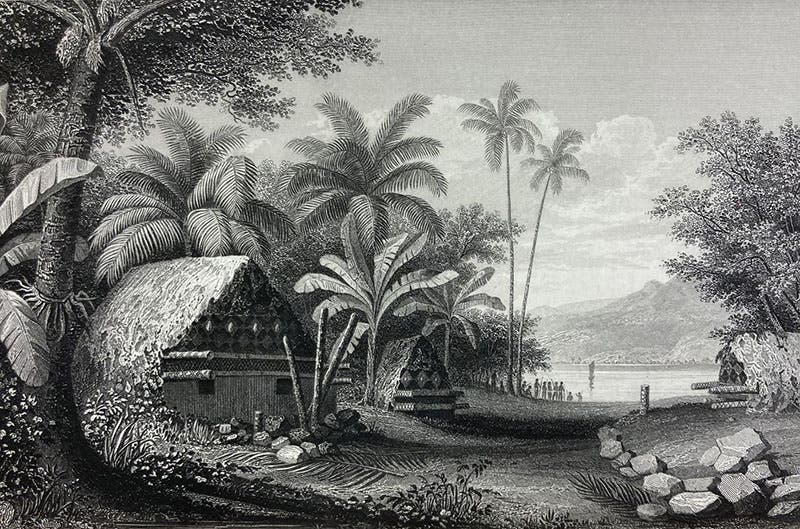

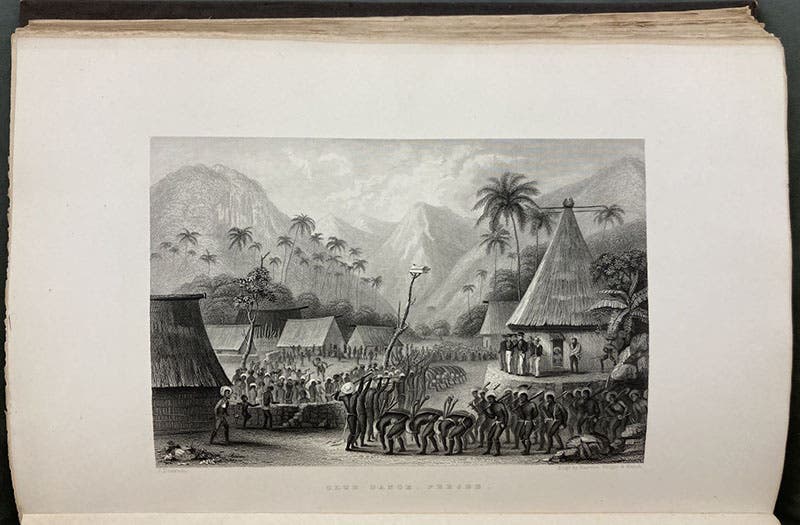

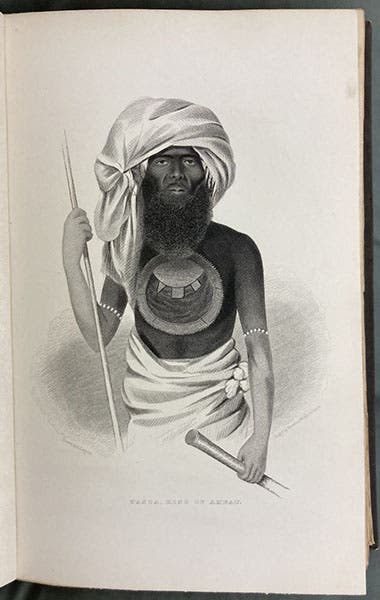

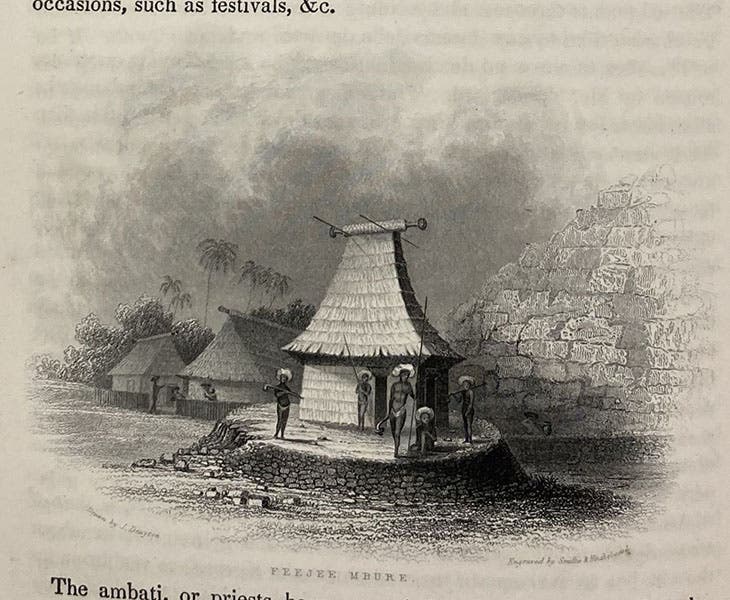

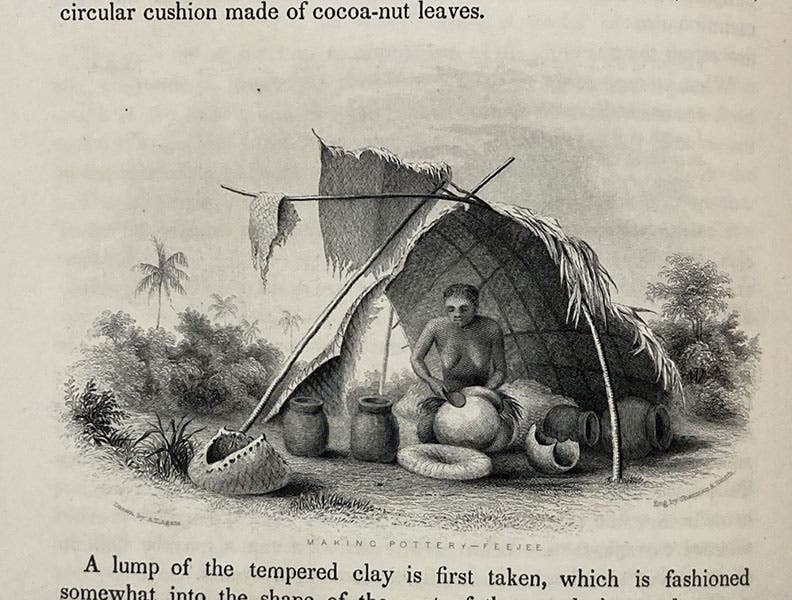

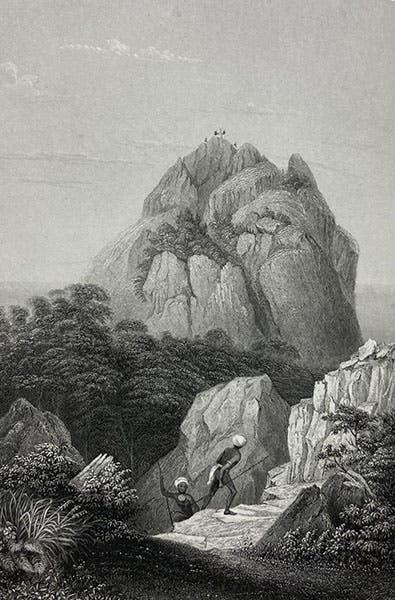

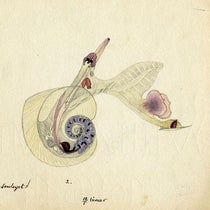

Today, we are going to look at an aspect of the US Ex Ex (as the U.S. Exploring Expedition is often abbreviated) that, until recently, was relatively unexamined, and that was the interest of Wilkes and the crew in studying and understanding the many human societies they encountered as they made their way across the Pacific Ocean. Ethnography was in its infancy in 1838; the French, for example, on their many voyages of circumnavigation, had focused on collecting animal and plant specimens, and mapping, and had made little effort to collect human artifacts or study how they were made or used. The Wilkes expedition was really the first to make the study of human cultures a priority. Wilkes had two skilled artists on board, Alfred T. Agate and Joseph Drayton, and much of their time was devoted to sketching scenes of human activities and social encounters. We have published a post on Agate. They also made portraits of tribal chieftains, showed craft practices, such as making pottery, and tried to capture religious rites and dances, examples of each of which we have included here.

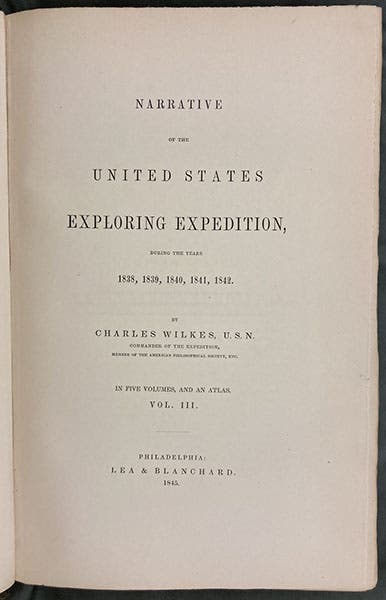

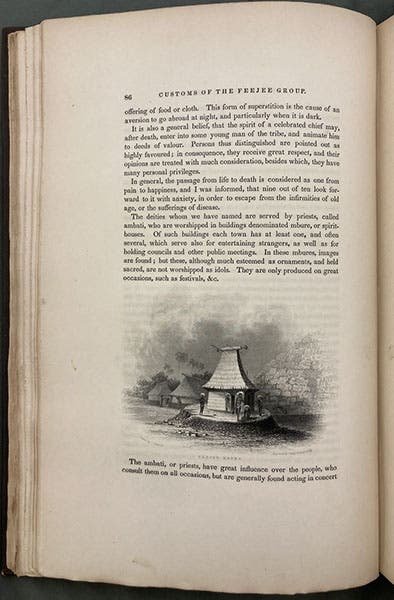

Part of the success of the Wilkes expedition in establishing ethnography as a worthy discipline can be attributed to the willingness of the U.S. Congress to spend money on the official publication. Authorities wanted the Ex Ex publication to be as impressive as the narratives of the two Astrolabe voyages. So they engaged the best engravers and printers to turn the drawings of Agate and Drayton into prints, and Wilkes did an excellent job of incorporating the engravings into his narrative, so that, really for the first time, images became an integral part of the story – they were included in the text, rather than in a separate plate volume, and they were discussed in the text as well, incorporated into the narrative. We drew our images today from Volume Three, which includes the encounters with the natives of Feejee (as Wilkes called Fiji) and Tonga and other island nations. This volume includes 12 full-page plates, 10 smaller vignettes in the text, and more than a score of wood engravings. The engravings (etchings in most cases) are incredibly detailed, each one costing hundreds of dollars apiece to prepare.

Wilkes’ Narrative was published in several formats. Most copies are in octavo format and do not have the full-page plates. The initial issue of 1845, however, was a quarto set (sometimes referred to as ‘imperial octavo’), on larger paper, and with the full-page engravings included. The five text volumes were supplemented by an atlas, which contains the maps of the voyages. We acquired our quarto set just after we mounted our exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance, in 2008, so the copy we displayed there was an octavo set of the same year.

In addition to the 5 volumes of the Narrative, there were supposed to be 19 supplemental volumes on specific subjects, such as Geology, or Mammals. Wilkes spent the next twenty years or so farming out this work, and supervising the editing, and even then, only 14 were published. We have four of the supplemental volumes, all in folio; we have written a post on one of the editors, John Cassin, who did the volume on mammals and birds after Wilkes fired the original editor, Titian Ramsay Peale.

In today’s post, we have tried to show some of the plates full-page, as you would encounter them in reading the book, and some, especially the vignettes, in close-up, so that you can appreciate the detail in the etchings.

There have been several excellent book-length studies of the Wilkes expedition. The most lavishly illustrated is an exhibition catalog for the Smithsonian Institution, Magnificent Voyagers: The U.S Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842, ed. by Herman J. Viola and Carolyn Margolis (1985). The other book I would like to mention was the first to focus on the importance of the Wilkes expedition for the social sciences: The Shaping of American Ethnography: The Wilkes Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842, by Barry Alan Joyce (2001). Both books are excellent.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.