Scientist of the Day - Charles Wheatstone

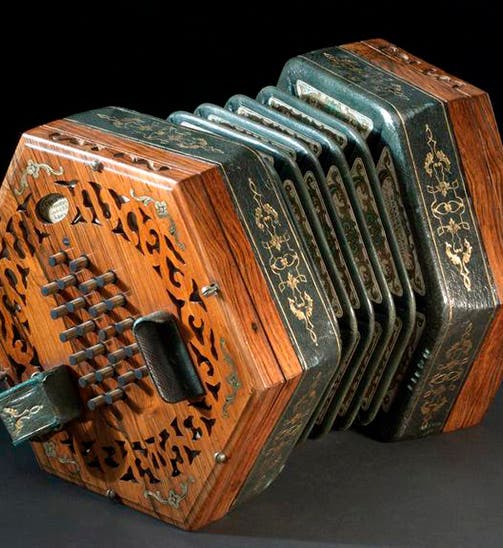

Charles Wheatstone, an English physicist and inventor, was born Feb. 6, 1802, in Barnwood, Gloucestershire. His father was a music teacher, and Charles was apprenticed at the age of 14 to his uncle, a seller of musical instruments. It is often said that the apprenticeship did not work out, but in fact Charles was involved with musical instruments for most of his life, inventing, most famously, the English concertina, which had the novel feature of key buttons for both hands which were played alternatively to produce rapid musical passages. There are many Wheatstone concertinas in the Science Museum of London, of which we show one here (first image).

Wheatstone became interested in electricity after reading Alessandro Volta’s account of the subject while still a young man. He built his own batteries, scrounging copper where he could, and did quite a few experiments. The most famous came later, when he was 32, and he measured the speed of electricity in a wire by introducing spark gaps and using a rapidly rotating mirror to measure the intervals between sparks, arriving at a speed of 288,000 miles per second, which was about 50% too high, but an admirable first attack on a problem that would only be solved decades later, by Hippolyte Fizeau, who did his famous experiments to measure the speed of light in 1849, using a similar system of rapidly-rotating mirrors.

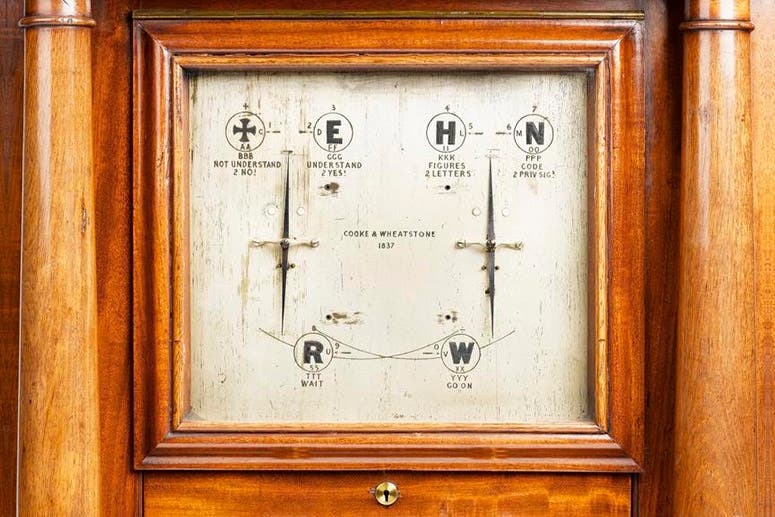

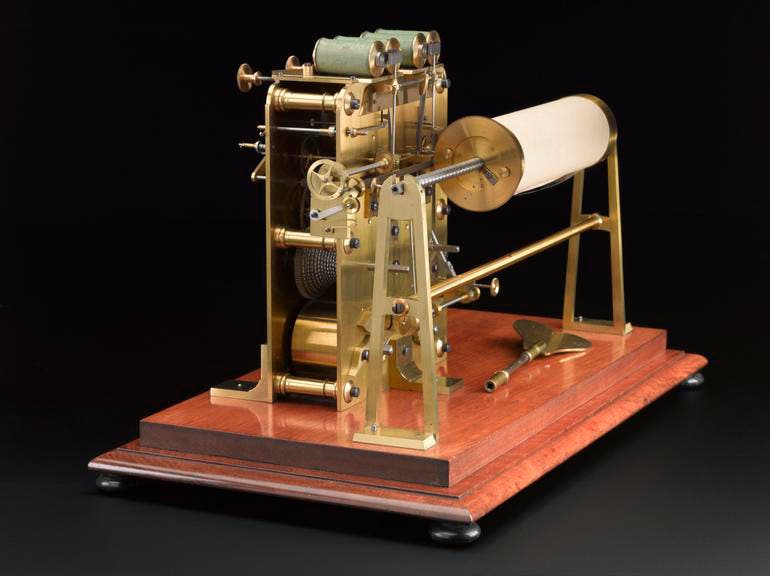

Wheatstone became interested in the problem of telegraphy early on, and in 1837, he teamed up with Thomas Cooke to work toward producing a commercial telegraph. A first, this was a five-wire system, and did not use a code, but rather an array of five magnetic needles which would deflect, depending on the signals, and point to a letter of the alphabet on a chart behind the needles. They transmitted their first signals on a line set up along the London and Northwest Railway in 1837, a distance of 1.5 miles, and two years later had moved to the Great Western Railway, and in 1841, sent signals from Paddington Station in London to Slough, a distance of about 18 miles. This was three years before Samuel F.B. Morse sent his famous message from Washington to Baltimore, inaugurating the American Age of Telegraphy. There are many ingenious Wheatstone transmitters and receivers in the Science Museum, of which, again, we show just one. Wheatstone built 5-needle, 4-needle, double-needle, and single-needle receivers, as well as printing receivers. He even built an automatic transmitter, which used a perforated tape to send signals about 5 times as fast as a human could manage. Wheatstone’s inventiveness was prodigious.

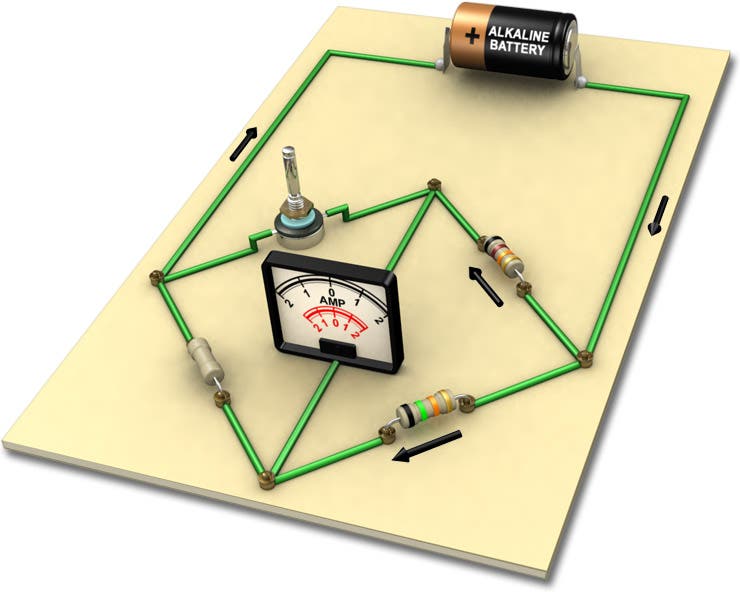

Wheatstone’s name is most commonly associated with the Wheatstone bridge, which he did not invent (that was done by S. Hunter Christie in 1833), but which Wheatstone then refined and described in a paper in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1843, and it became ever associated with his name, not poor Christie’s. The Wheatstone bridge is an ingenious set up of resistors, a battery, and a galvanometer, which one can use to find the ohm-value of an unknown resistor with great accuracy. One simply plugs the unknown resistor into the circuit, adjusts a variable resistor until there is no current flowing through a part of the setup (the meter needle reads zero) and the value is determined with a simple equation. There are many Wheatstone bridges in the Science Museum, but with no indication that any of them are even close to being original Wheatstone constructions. The easiest way to appreciate the setup of a Wheatstone bridge is to look at a modem diagram (fifth image), and then, if you want to understand how it works, take a look at the clever animation on this webpage.

There are many more Wheatstone creations that one could discuss – for example, his invention of the mirror stereoscope (1838; sixth image), or his work in cryptography, with the invention of the Playfair cipher (1854), which was used for British wartime communications up through World War II. I would try to explain it to you, but I can’t even explain it to myself. Perhaps you will have better luck with the Wikipedia article than I did. Wheatstone was also interested in underwater telegraphy and was consulted on the attempts to lay transatlantic telegraph cables in 1857-58 and 1865-66.

Wheatstone was knighted in 1868 and widely honored by all manner of scientific organizations before his death in Paris in 1875 of a lung inflammation. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery in London, where he shares hallowed ground with several other persons of great ingenuity, including Marc Isambard Brunel, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and Charles Babbage.

Wheatstone’s success with the Wheatstone bridge should not be confused with the achievements of Charles Wheat, whose erection of a different kind of Wheatstone Bridge in Connecticut was described in our April First post of 2019.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.