Scientist of the Day - Charles Tilston Bright

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Charles Tilston Bright, a British electrical engineer, was born June 8, 1832. Bright is best known as the chief engineer on board the ship Agamemnon when the first successful Atlantic cable was laid in 1858. Bright was knighted within a week, which was lucky for him, for the cable failed within a month, and service was never restored. The failure was not Bright's fault, for it was determined that his chief electrician liked to test the cable, as it was being laid, with an induction coil that generated up to 2000 volts, which ultimately fried the cable. So Bright emerged with only a little tarnish on his reputation. And he kept his knighthood.

Bright was subsequently involved in another venture that is not so well known, but was perhaps more impressive, since it was successful. After the Indian Mutiny of 1857 and the breakup of the East India Company in 1858, the British government desperately needed to improve communications with India, which Britain still ruled. In 1859, a submarine cable company laid a 3000 mile cable down the Red Sea and across the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea to India; it was a bust, as the cable failed everywhere and was deemed irreparable. Bright meanwhile successfully laid four submarine cables from Spain to the Balearic Islands (Majorca, Minorca, etc.) in 1860, so he was called upon in 1862 to be chief engineer for a cable from the mouth of the Persian Gulf to India, essentially from Kuwait to Karachi. Arranging rights-of-way was a nightmare, since 9 different countries, principalities, or sultanates were involved, but fortunately, Bright did not have to worry about the diplomatic end. He just had to come up with a cable design that would escape the fate of the Red Sea cable, and then supervise the laying of the cable.

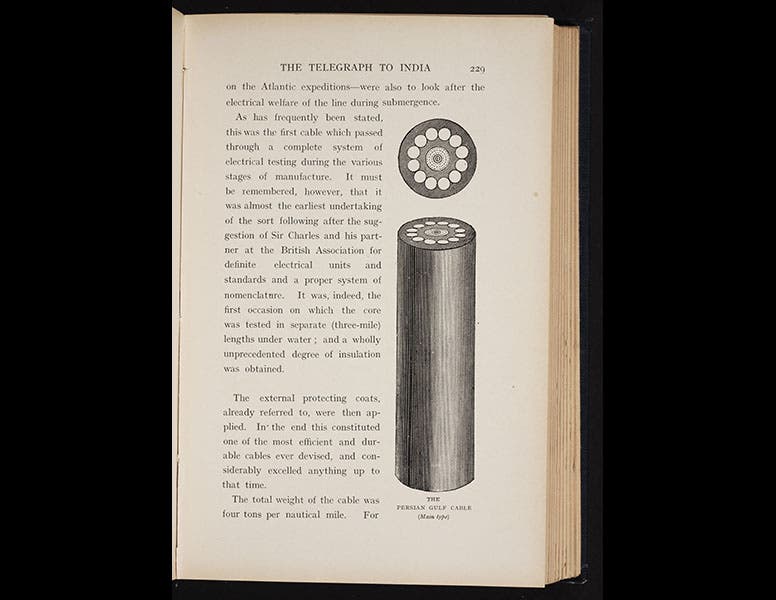

The cable was made in England by two companies: the Gutta Percha Company made the core, consisting of the copper conductor and a gutta-percha insulating covering, while Henley's Telegraph Works surrounded the core with creosote-soaked hemp, then twelve iron wires to support the weight, then more hemp and an outer liner. We see above a cross-section of the Persian Gulf cable – it is about an inch and a quarter in diameter (first image). The copper conductor, which looks solid, is actually made from four quarter-round copper wires that have been drawn and squeezed together, thus combining the best features of a stranded conductor and a solid conductor. You can’t see this in the modern photo of the cable, but you can if you look closely at the drawing (fifth image).

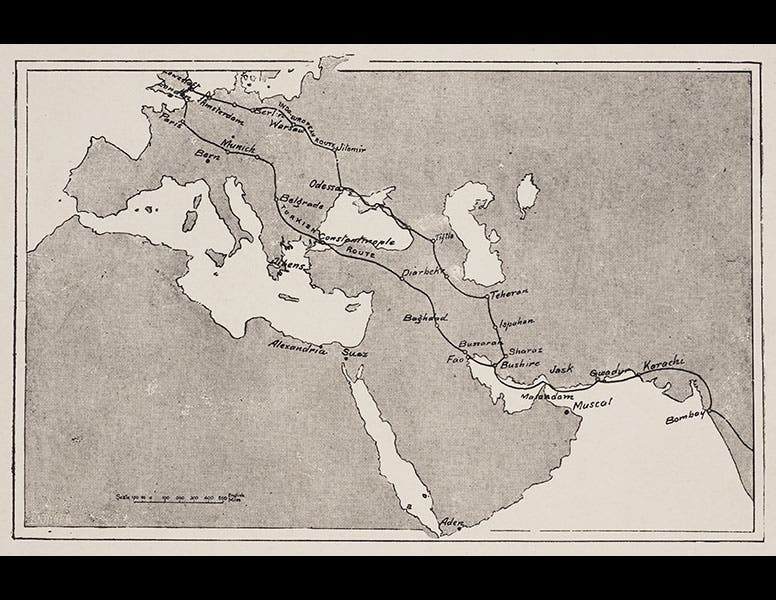

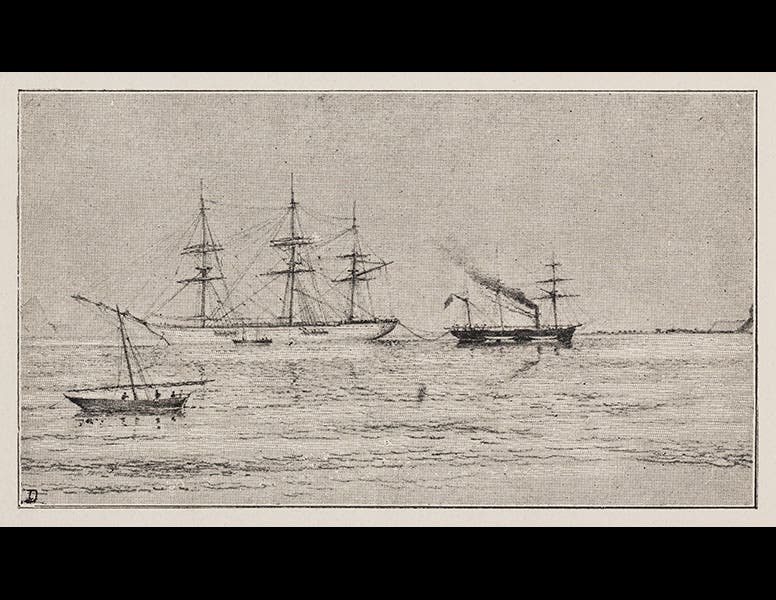

The cable was loaded into five separate ships, and each one completed a leg: from al Faw at the head of the Persian Gulf to Bushire in Persia (Iran) to the peninsula of Musandam in the Strait of Hormuz (modern Oman) to Gwadar and then on to Karachi (both now in Pakistan; Karachi was then part of India; third image). Completed in April of 1864, the cable worked from the get-go, although there were plenty of intermittent problems, and it took another year for Turkey to complete the landline from Baghdad to Constantinople (Istanbul) so that London could talk to India.

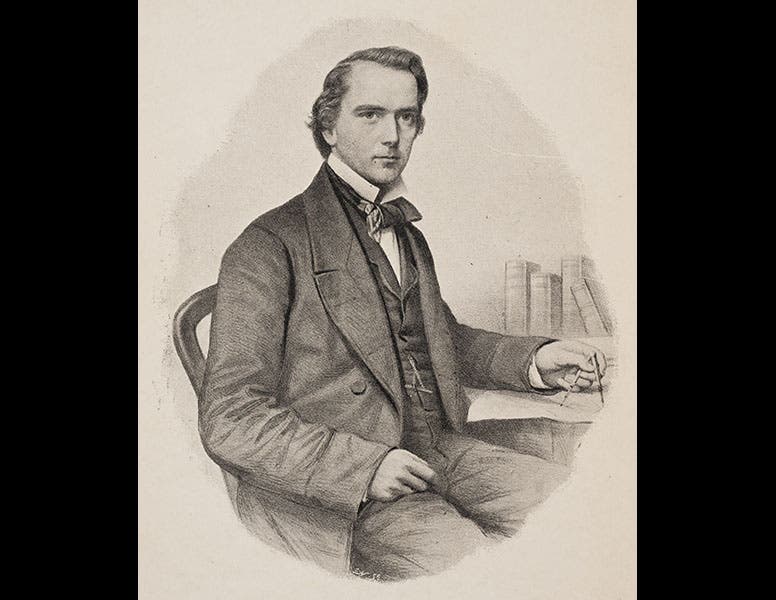

Bright’s son was also a successful electrical engineer and took the time to publish a Life Story of his father (1898), with a frontispiece portrait of Sir Charles (second image). We have a 1908 revised edition of this book in our Library, and all of the images above except the first are taken from it. The sketch of cable-laying in the Persian Gulf (fourth image) was made by Charles Bright himself.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.