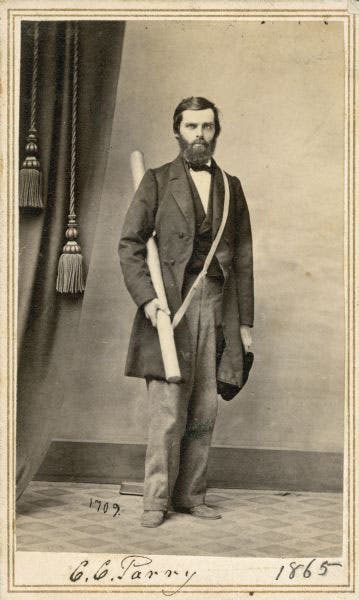

Scientist of the Day - Charles Parry

Charles Christopher Parry, an English/American explorer and botanist, was born Aug. 28, 1823, in Gloucestershire, England. He came to New York when he was 9, studied medicine and botany there, received a medical degree, and eventually ended up as a physician in Davenport, Iowa. Two of his teachers in New York were Asa Gray and John Torrey, both eminent botanists and advisors to the Western railroad surveys that began in the late 1840s. Consequently, Parry was invited to join the U.S.-Mexican Boundary Survey (1848-55), where he spent 3 years collecting plants along the Mexican border, while making the acquaintance of George Engelmann of St. Louis, another prominent botanist who published a book on the cacti discovered by the survey. Parry contributed to the Report on the United States and Mexican Boundary Survey, written and edited by the survey leader, William H. Emory, which we have in our collections.

While keeping up his practice in Davenport, Parry spent considerable time in the 1850s and 1860s collecting plants in Colorado, where he also seems to have been attracted to mountaineering. He climbed many peaks in Colorado's Front Range, and turned a pleasure into a scientific pursuit by measuring the altitudes of his ascended peaks with a barometer. Three of the mountains he was the first to climb he named after Gray, Torrey, and Engelmann, all three of which are about 50 crow-flying miles west of Denver, and all are fourteeners, meaning they exceed 14,000 feet in altitude.

Subsequently, a near-fourteener was named after Parry – I have been unable to determine who named it. Parry Peak, sticking 13,390 feet up into the thin Colorado air, is a little bit north of the Gray-Torrey-Engelmann trio of mountains, not too far from James Peak, named after yet another exploring botanist, Edwin James. Each of these peaks has a Wikipedia entry, if you want to look them up. You can see a view of James Peak all by itself at our post on James, and here we show a panoramic view from I-70 going west, which includes both Parry Peak and James Peak. Parry Peak has a lot of company in the world of mountains – there are 637 thirteeners in Colorado, while there are only 53 fourteeners in the state.

To frost the cake, Parry also discovered the Engelmann spruce and the Torrey pine, and named them after his mentors.

I am guessing that, in the taxonomic sciences, when you name a species (or a mountain) after someone, they feel a certain responsibility to return the favor. This might explain why Charles Parry has at least 20 plant species named after him, by my count, and there are probably more. They were mostly named by Gray and Engelmann (Torrey was pretty much done naming plants by this time). I chose several of the more photogenic Parry eponymic plants to include here, including the devil’s pincushion, Echinocactus parryi, named for Parry by Engelmann (fifth image), and Parry's lily, more commonly called the lemon lily, a rare desert mountain lily that was named for Parry by Sereno Watson, assistant to Gray at Harvard (sixth image). Parry’s penstemon was named by Gray (seventh image). It should be noted that all of these plant species were discovered by Parry, so it is not inappropriate that they should carry his name.

In 1872, when Asa Gray was 61 years old, he journeyed west from Harvard to Colorado to see the peak that Parry had named in his honor, and then climbed it. It is said that John Torrey saw his peak the same year – he was then 76 years old. Perhaps they travelled west together, on the new transcontinental railroad. For Torrey, it was just in time, as he died the following spring.

Parry himself lived until 1890, dying at the age of 66. He was buried in the cemetery he himself founded in Davenport. You can find a portrait (different from ours) and two photos of his simple memorial stone on the Findagrave website, which also provided our photo of Parry’s lily.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.