Scientist of the Day - Charles Macintosh

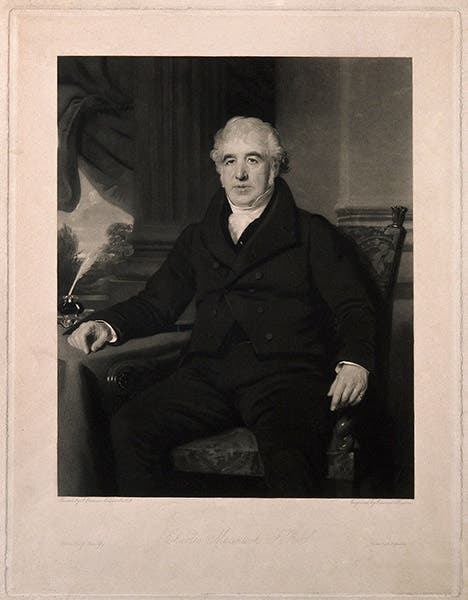

Charles Macintosh, a Scottish chemist, was born Dec. 29, 1766, in Glasgow, Scotland. His father manufactured dyes, and Charles was expected to take over the family business. He did learn a lot about chemistry, both in Glasgow and at the University of Edinburgh, where Joseph Black was teaching, but he ended up pursuing his own chemical dreams. He, working with Charles Tennant, invented a bleach powder for bleaching wool that made him a considerable amount of money, allowing him to pursue his own chemical inclinations.

One of the more robust chemical industries of the 1810s was the production of lighting gas from coal, and an unwanted byproduct of the process was coal tar, which Macintosh could buy cheaply. One of the components of coal tar was naphtha, with which Macintosh experimented, discovering that naphtha was an excellent solvent for rubber. He developed a process by which he could liquify rubber and spread it between two pieces of wool cloth. When it dried, the cloth was fully waterproof. Macintosh had invented the first truly waterproof fabric, and he secured a patent in 1824, and started manufacturing waterproof cloth that very year.

I am not sure how the arctic explorer John Franklin heard about the new rubberized fabric so soon after its invention, but in 1825, he was headed back on a second expedition to the Canadian arctic, after a disastrous first expedition during which most of his company died (see the entry on Franklin’s first expedition in our exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance). He took with him, on the second expedition, two outfits of waterproof clothing for each person, and the stores of flour, pasta, chocolate, coffee, and tea were divided up into 85-pound bundles, each of which was wrapped in three layers of waterproof canvas. Franklin also took along a small boat that they called the “Walnut-shell,” which was "covered with Mr. Mackintosh's prepared canvas." It weighed only 85 pounds, and was fully portable, and Franklin had it designed to prevent a recurrence of a tragedy from the first expedition, when a number of his men were stranded on the wrong side of a river and could not get across, and eventually perished, for want of a portable boat. Twenty years later, Peter Halkett invented an inflatable boat made of Mackintosh rubberized cloth that was even more successful than the Walnut-shell, because before you blew it up to become a boat, you could wear it as a cape. We have written a post on Halkett. And there is an entry on Franklin’s second expedition in Ice: A Victorian Romance.

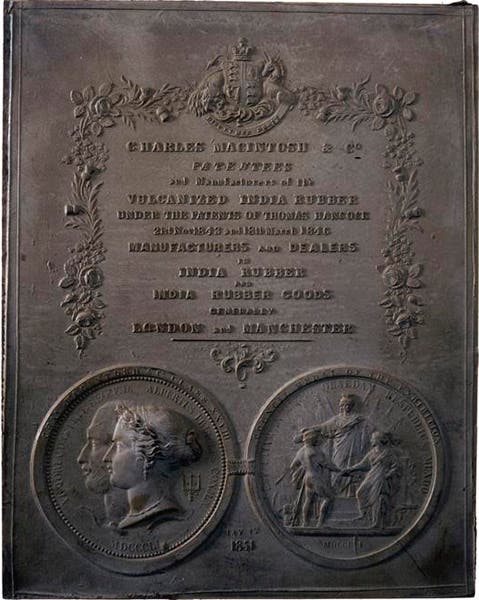

Macintosh’s Glasgow company eventually merged with the firm of Thomas Hancock of London; Hancock had invented a "masticator" that could shred used rubber products so they could be re-used, and it turned out that the shredded rubber was more receptive to solvents and produced better rubberized fabrics. Hancock soon discovered vulcanization, independently of Charles Goodyear in the United States, and Chas. Macintosh and Co. then began producing products of vulcanized rubber. At the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition, the booths of Macintosh and Hancock were a big success. The Science Museum in London has a vulcanized rubber plaque that was prepared especially for the Exhibition, presenting the rubberized likenesses of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert (third image).

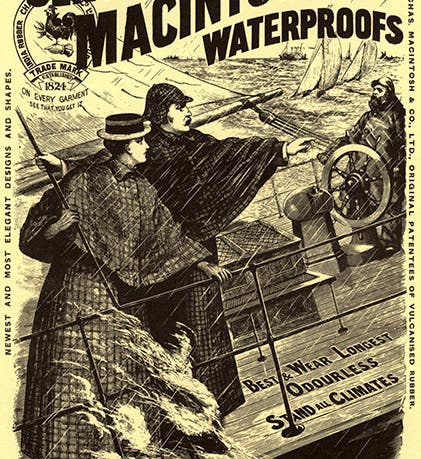

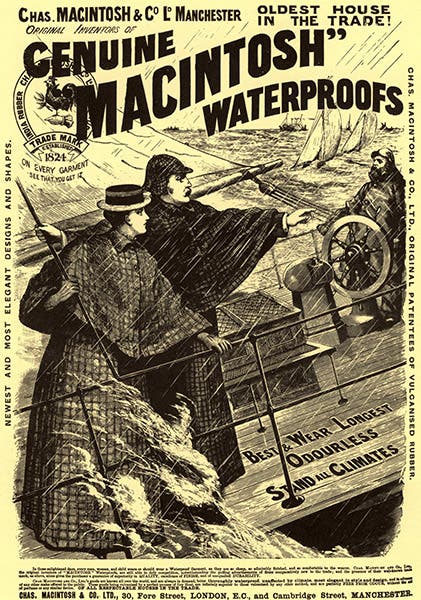

Macintosh died on July 25, 1843, so he never got to see his Mackintosh garments become fashion items, as they did in the later Victorian era (first image). No one seems to know how Macintosh the man was imperfectly eponymed into Mackintosh the waterproof coat, although I note that Franklin in 1828 was already referring to rubberized fabric as "Mackintosh's prepared canvas."

Macintosh was buried in the graveyard of Glasgow Cathedral, where there is a gravestone for Charles, his two parents, and his wife Mary Fisher (fourth image). Why no one thought to give him a more unique rubber memorial stone, like the one fashioned later for Victoria and Albert, I do not know.

Google celebrated the 250th birthday of Charles Macintosh in 2016 with one of their better "Google doodles" (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.