Scientist of the Day - Charles-Lucien Bonaparte

Charles-Lucien Bonaparte, a French naturalist, died on July 29, 1857, at age 54. Charles was the son of Lucien Bonaparte, younger brother of Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon wanted his brothers to marry into royal families across Europe, but Lucien fathered a son (Charles) with a young widow and then married her to legitimize the child. Napoleon was furious, since he had no male heir, and now Lucien's sons, born to a commoner, were ineligible to succeed Napoleon. Lucien did not care – he loved his wife, who was cultured and talented and much more appealing than any of the eligible princesses he might have ended up with. He refused to divorce his wife, and bought an estate in Italy, where Charles was raised. He learned to speak both Italian and French fluently, and to read Latin, and his interest from childhood was natural history, first insects, and then birds. His father did not approve, but the Bonapartes were used to disapproval, and Charles pursed his interest diligently, becoming quite expert in bird taxonomy by the time he was 18.

The Lucien Bonapartes had to move to England after Napoleon’s 100-day reign, and Charles decided to relocate to America, where another one of his uncles, Joseph, the father of his young wife (and cousin), had moved with his family and built a beautiful estate in New Jersey, not far from Philadelphia.� Charles and his pregnant wife arrived in 1823 – Charles was just 20 years old – and Charles proceeded to make rapid inroads into the natural science community in Philadelphia, joining the American Philosophical Society and the Academy of Natural Sciences (ANS). The study of birds at the ANS was presided over by George Ord, who had seen the last volumes of Alexander Wilson’s American Ornithology through the press in 1814. Ord rebuffed John James Audubon’s attempt to join the ANS, because he was seen as a threat to Wilson’s legacy, and apparently Ord tolerated Charles only because he was a prince (or so Charles called himself).

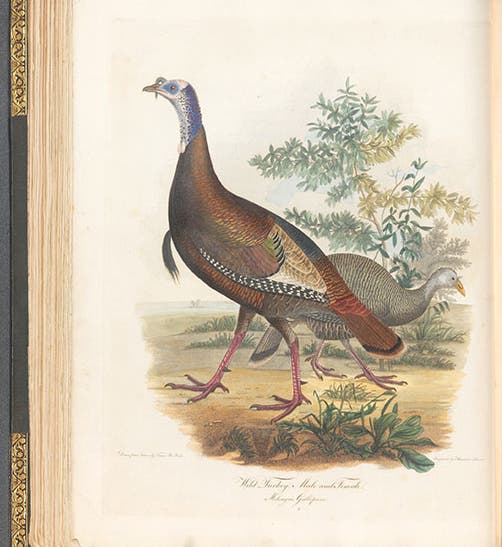

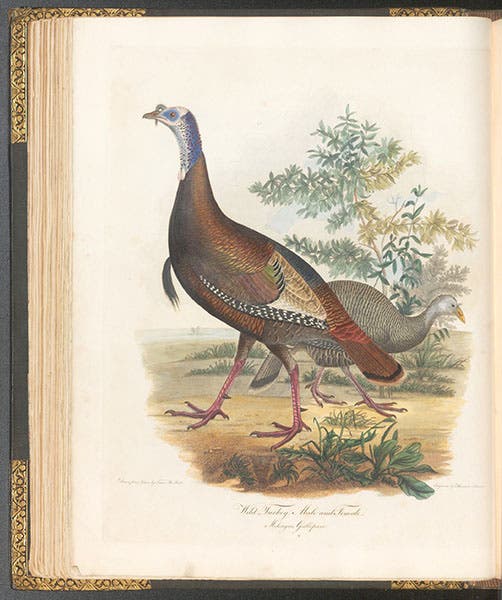

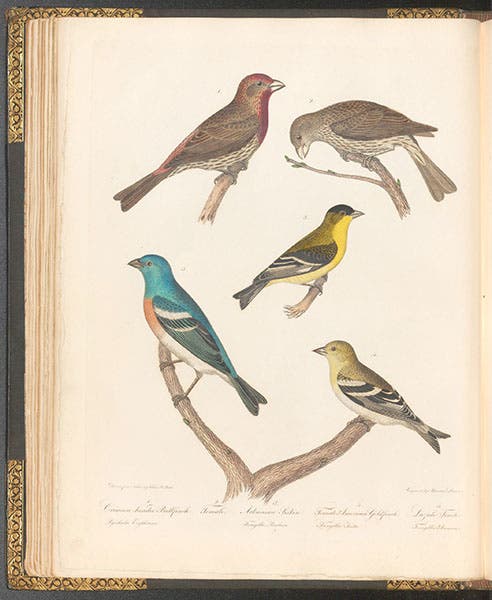

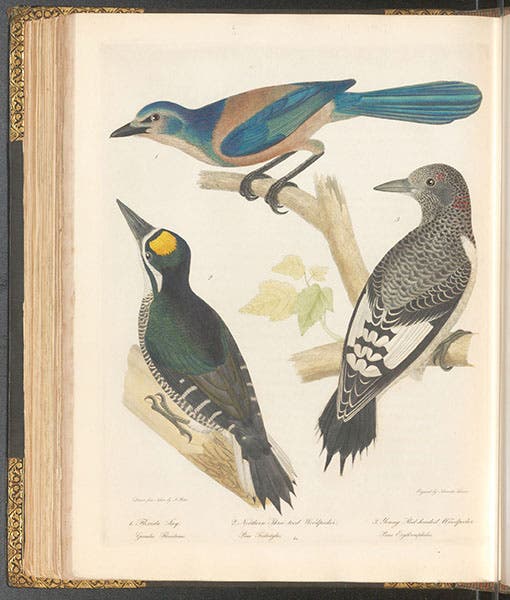

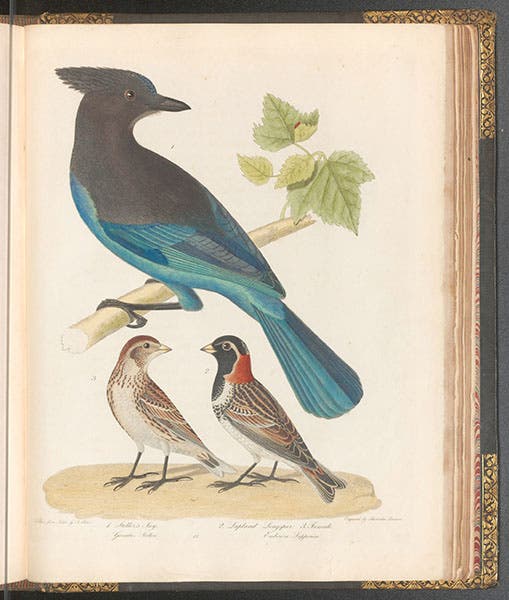

Charles became good friends with Thomas Say, who had journeyed out West with the Long expedition in 1820, and had bought back many bird specimens unknown to Wilson. So Charles decided to publish a new “American Ornithology,” this one with birds that were not included in Wilson’s work. It was a bold and brash move for a young man only 22 years old, who had written English for only a few years, but Charles did know his stuff, and his American Ornithology was an impressive scholarly achievement. The full title was: American Ornithology; or, The Natural History of Birds Inhabiting the United States, not given by Wilson (1825-33). We have the four-volume set (bound in two volumes) in our library, as well as Alexander Wilson’s 9-volume compilation (bound in 3, 1808-14).

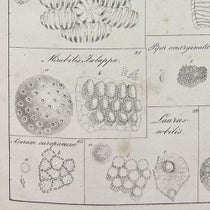

The birds in the first volume were illustrated by Titian Ramsay Peale, the youngest artistic son of Charles Willson Peale. However, Charles grew weary of Peale’s tardiness in submitting drawings, and he switched to Alexander Rider for the remaining 3 volumes. Rider was not as talented as Titian, but he did meet his deadlines. We show you here five plates from the first two volumes, three by Peale and two by Rider, as well as several details of individual birds. Wilson’s and Bonaparte’s bird paintings seem a little plain to some of those accustomed to the lavish settings of the birds of Audubon and John Gould; others like their simplicity. The lazuli finch (now lazuli bunting) in our fourth image was one of many birds that were discovered by Thomas Say and brought back to Philadelphia to be described and named, as it turned out, by Charles-Lucien Bonaparte.

Charles left the United States with his family in late 1826, before his second and later volumes were even printed, and would never return. He moved his family to Italy, where he had a long and prolific career. We would like to acquire his beautiful work on the animals of Italy, Iconografia della Fauna Italica (3 vols., 1832-41); if we ever do, this will call for a second post on Charles. Meanwhile, to learn about the rest of his life, including his political activism, I highly recommend The Emperor of Nature: Charles-Lucien Bonaparte and His World (2000) by Patricia Tyson Stroud, which we have in the Library.

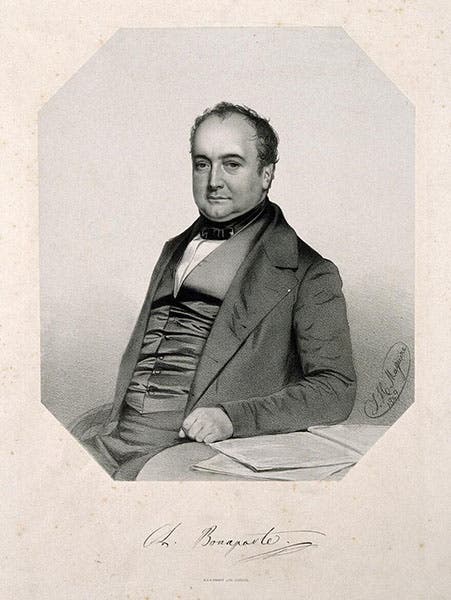

The portrait we include, a lithograph by Thomas Herbert Maguire, was done in 1849 (second image). We have shown quite a few portraits by Maguire in this series, since he did many scientists, but this is the only Maguire portrait I know that depicts someone who was not British. One can certainly see in Charles the family resemblance to Napoleon.

This is a revised and expanded version of an earlier post on Bonaparte, published on July 29, 2015.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.