Scientist of the Day - Charles Lesueur

Portrait of Charles Alexandre Lesueur, oil on canvas, by Charles Wilson Peale, 1817-18, Library, Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Drexel University (photo provided by Robert Peck)

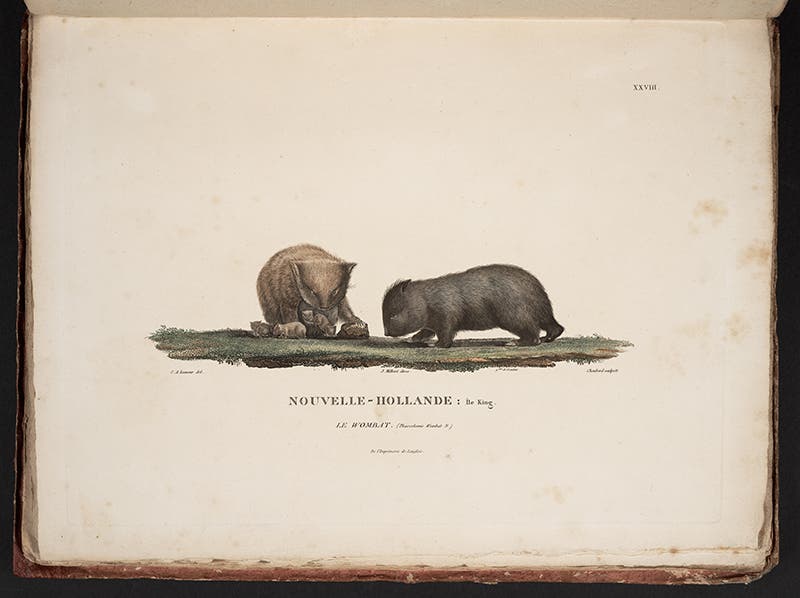

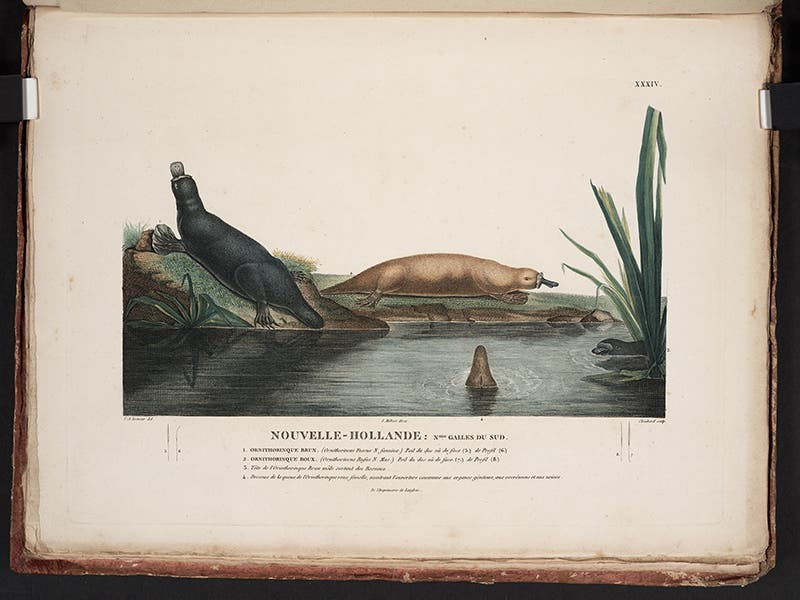

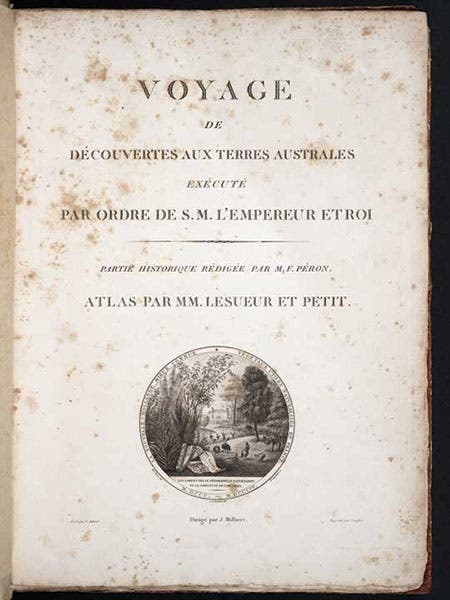

Charles Alexandre Lesueur, a French naturalist and artist, died Dec. 12, 1846, at the age of 66. In 1800, as a young man of 22, Lesueur had sailed on Nicolas-Thomas Baudin’s voyage to Australia, as a gunner with artistic abilities. Before long, he was the only sailor still alive who could draw, and he began making sketches for the only surviving zoologist, François Péron. Most of the engravings of animals in the published narrative by Peron (Capt. Baudin died on the voyage and Péron was left with the task of writing the narrative) were done by Lesueur. We include two of those here, in the form of hand-colored engravings, showing a family of wombats (second image) and a pair of platypus (fourth image), this one rather crudely drawn, but the platypus was brand new to zoologists at this time. We also include a detail of the engraving of the wombats, so that their impish expression does not go unnoticed (third image)

We exhibited Peron’s Narrative in our 2009 exhibition, The Grandeur of Life, and in the online version of the catalog, you can see two more of Lesueur's engravings, depicting a family of banded hare-wallabies, and a gaggle of black emus. Many of the exotic plants and animals that were brought back alive ended up on the grounds of Malmaison, the estate of Napoleon's wife Josephine just west of Paris, and Lesueur did a drawing of Josephine's front lawn, where the wallabies and black emus, along with some black swans, seem to have found a home (fifth image). This small engraving appeared on the title page of Péron’s narrative, which you can see in its entirety in our sixth image.

In 1816, Lesueur met William Maclure, a naturalist from Philadelphia who was visiting Paris; Maclure needed an artist, and the two toured together for over a year. When Maclure returned to Philadelphia, Lesueur went with him. Lesueur would remain in the United States for 21 years, touring extensively. He joined the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and began publishing papers on natural history, as well as illustrating the papers of other academy members. Lesueur was one of the first natural history illustrators to learn lithography (a new print technique invented just before 1800; see our post on Alois Senefelder), and in 1822, Lesueur published a paper on a fish he had discovered, Cichla aenea, and he illustrated it with a lithograph that he did himself. It was the first scientific lithograph printed in this country, and we displayed it in our 2013 exhibition on lithography, Crayon and Stone, which was unfortunately never afforded a catalog, but you can see it here (seventh image). Maclure used a crayon rather than a pencil, so his image exhibits the wonderful charcoal-like texture so characteristic of a fine lithograph, as we see in the detail (eighth image).

Lesueur also taught painting in Philadelphia at an innovative school run by a Mme Fretageot, and one of his pupils was a young woman named Lucy Way Sistaire. When the social reformer Robert Owen swept through Philadelphia in 1825, Lesueur, Maclure, Lucy, and the botanist Thomas Say followed Owen to his new utopian community in New Harmony, Indiana. On the way out, Lucy married Thomas Say and became Lucy Say. We have published posts on both Lucy Say and Thomas Say.

The Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadephia has a portrait painted by the notable Charles Willson Peale that is believed to represent Lesueur (his name is on the frame plate); it is thought to date to 1817-18, when Lesueur was 39-40 years of age (first image). As best I can determine, it is the only portrait of Lesueur that survives. I thank Robert Peck at the Academy for providing this image on short notice. In addition to the portrait, the Academy has a collection of 70 original pieces of artwork by Lesueur, even including some of the engraved copper plates used to print his drawings. You may see an illustrated inventory here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.