Scientist of the Day - Charles Lapworth

Charles Lapworth, an English geologist, was born Sep. 29, 1842, in Farmington, Berkshire, and died on this date, Mar. 13, 1920, in Birmingham, at age 77. He spent 11 years as headmaster of a school in Galashiels in southern Scotland, and during that time became familiar with the convoluted geology of the region known as the Scottish borders.

At the time Lapworth moved to the borders, there was a conflict raging known as the Cambrian-Silurian controversy. Back in the 1830s, the Cambridge geologist Adam Sedgwick, investigating the rocks of northern Wales, had found a system underlying the "Old Red" sandstone that he named the Cambrian system (Charles Darwin spent a month with Sedgwick in Wales before he headed out on the Beagle).

Meanwhile, a gentleman geologist from London, Roderick Murchison, was investigating the rocks of southern Wales, and he too found a new system of rocks beneath the Old Red, but different from Sedgwick’s, in that it contained primitive fossils such as trilobites. He called his system the Silurian, and it appeared to be younger than Sedgwick's Cambrian, but older than the Old Red, which would soon be called the Devonian.

Sedgwick and Murchison were at first the best of friends and worked to determine the boundaries between their two new systems. But as Murchison became more powerful (he eventually became head of the Geological Survey when Henry De La Beche died), he began to include lower and lower formations in his Silurian system, formations that he appropriated from Sedgwick's Cambrian, calling it Lower Silurian, eventually co-opting the Cambrian system entirely within his Silurian. Sedgwick did not take this well, and eventually the two men became bitter enemies and no longer spoke, with most of the bitterness lying in Sedgwick's camp. This was the state of geological affairs when Lapworth came on the scene in the 1860s.

The rocks of the Scottish borders, collectively called greywacke, befuddled everyone, because the layers were so thin and fossil-poor, and there was so much of it, tens of thousands of feet of strata, bent every which way. They were thought to be lower Silurian, but without the trilobites of the Welsh Silurian. The only recognizable fossils were graptolites, mysterious organisms that looked like writing in the rocks, hence the name (first image). Lapworth spent many years collecting graptolites and sorting out their differences, naming quite a few species. He came to realize that different formations had different species of graptolites, with virtually no overlap. Using the graptolites as index fossils, he discovered that the thousands of feet of rock layers in the Scottish borders were in fact just a few hundred feet of strata, five different formations that had been folded and inverted and piled up to a prodigious thickness by geological forces acting over eons of time.

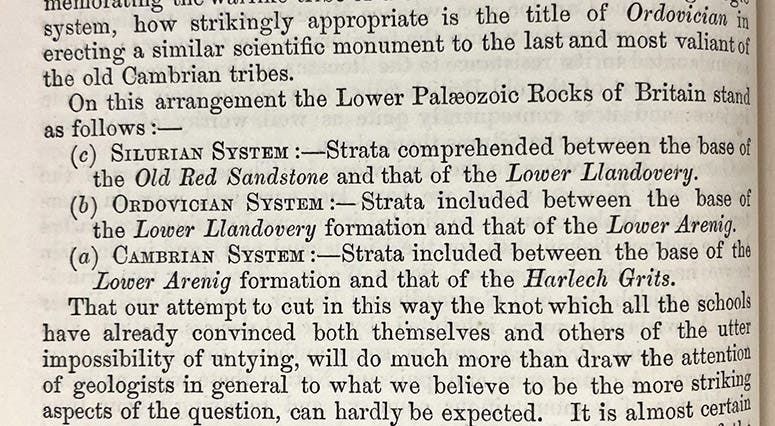

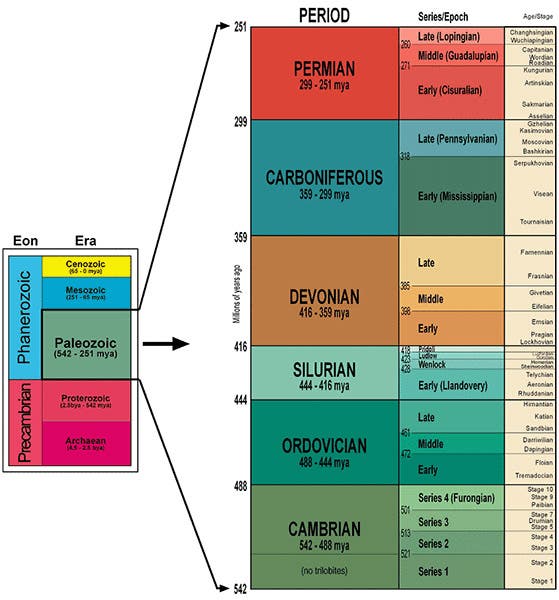

Lapworth was then able to match up his sequence of formations with those mapped in Wales, using his unequalled knowledge of graptolites. His top two formations seemed to be Silurian. His bottom layer matched the Upper Cambrian of Sedgwick. But the two layers in the middle were sui generis and must represent a new system, which he named the Ordovician, and he placed it squarely between the Cambrian and Silurian systems, and below the Devonian. It was the last major addition to the geological sequence that you will find in any geology textbook (sixth image).

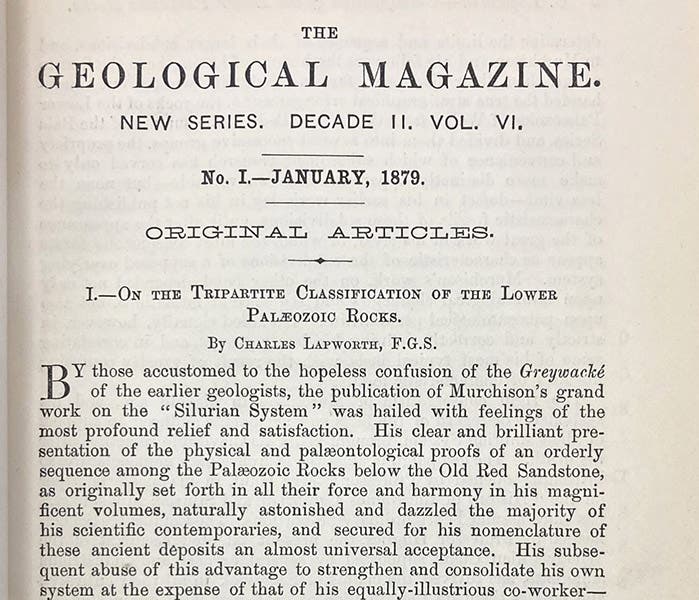

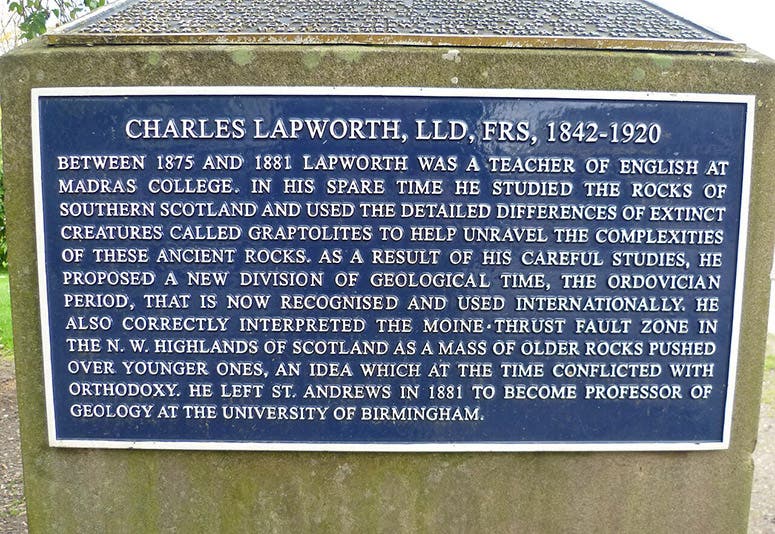

Lapworth published his conclusions, and his proposed Ordovician system, in 1879, after both Murchison and Sedgwick had died, unreconciled to the end (fourth and fifth images). It took some years for the Ordovician to be accepted as a system – no one besides Lapworth really understood the graptolite evidence. At the time, he was teaching English at Madras College, the secondary school run by St. Andrews, a job he took in 1875. In 1881, he was finally offered a professorship in geology at the University of Birmingham, where he taught until he retired in 1913. He would in the 1880s propose a resolution of the "Highlands controversy,” relating to the formations of northern Scotland, but that is a story for another time.

There have been half-a-dozen really good books on the geological controversies of Victorian England, but most are difficult to follow for the layperson. However, I can recommend a fairly recent book by Nick Davidson called The Greywacke (2021), which has an entire chapter on Lapworth and explains his achievements in some detail, but in an understandable fashion. It also explicates the Sedgwick-Muchison affair quite nicely.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.