Scientist of the Day - Charles H. Sternberg

Charles H. Sternberg, dinosaur hunter extraordinaire, was born June 15, 1850, in New York state. When he was 17, his family moved to Ellsworth County, Kansas, and there Sternberg stayed. He was interested in fossils and discovered that Kansas, once at the bottom of an inland sea, was littered with them. He married and raised three sons, and over a fifty-year career, he and his sons found an incredible variety of Mesozoic fossils and distributed them to museums around the world. Most of the notable fossils he found in Kansas were marine vertebrates, such as mosasaurs, as well as leaves, which Charles H. specialized in recovering. The family did not hunt dinosaurs at first, because there are no dinosaurs in Kansas.

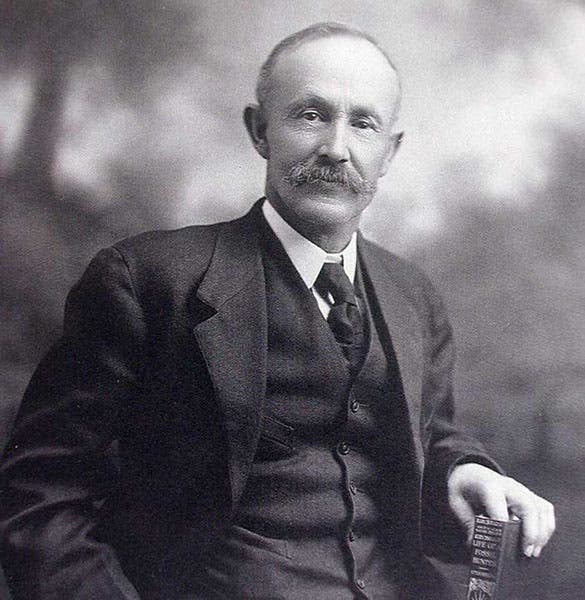

But Sternberg came to the attention of Edward D. Cope in Philadelphia, who supported Sternberg on several fossil-gathering expeditions in Wyoming, and at the end of the century, Sternberg turned his attention to dinosaurs and spent considerable time in the badlands of the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada. We are going to focus on Sternberg and dinosaurs here, because I have on my desk the Library’s autographed presentation copy of Sternberg’s book, Hunting Dinosaurs in the Bad Lands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada (1917). All our images except the portrait (seventh image) are drawn from this book.

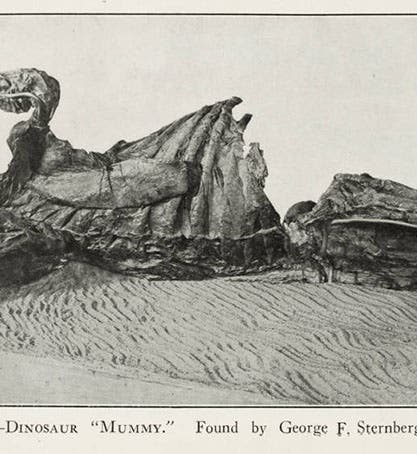

Sternbergs’ most remarkable find has to be the "trachodon mummy" that he unearthed in Converse County, Wyoming, in 1908 (first image above). This specimen had most of the skin and portions of the muscles preserved in fossilized form, as well as the complete skeleton. It was sold to the American Museum of Natural History in New York for the handsome sum (in those days) of $2000, where it is still on display (although it is now called it the Edmontosaurus mummy).

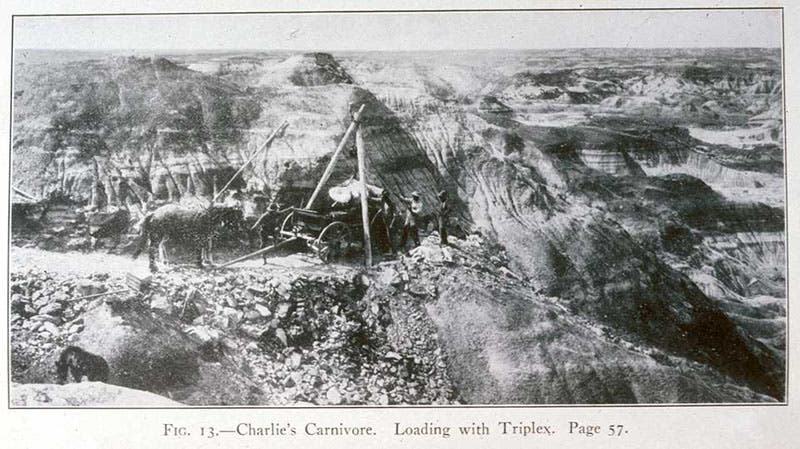

Most of the rest of Sternberg’s notable dinosaur finds came out of the bluffs along the Red Deer River in Canada. Sternberg’s son Charles M. found a carnivorous dinosaur embedded in the rock that was almost complete – they called in “Charlie’s carnivore” before it was eventually named Gorgosaurus (some consider it to be the same as Albertosaurus, and some do not). You can get a good idea, from the photograph of the bone-embedded slabs being loaded onto a wagon (second image, above), just how rugged this territory is. Sternberg planned to prepare a free-standing mount for the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, but he spent a year touring the east coast and consulting with experts in Pittsburgh, Princeton, Yale, and Washington, D.C., and all agreed that since the skeleton was still articulated, it should remain in its matrix, and Sternberg accordingly changed his mind.

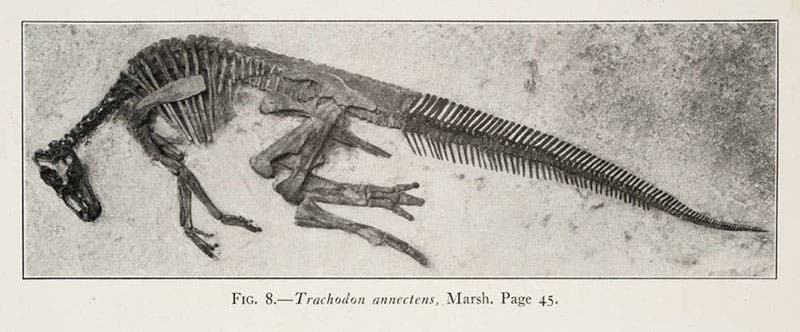

There are many other photographs in the book of museum specimens collected by Sternberg and his sons, and of their work in the field. We see in the third image a trachodon skeleton, nearly complete and still in its matrix.

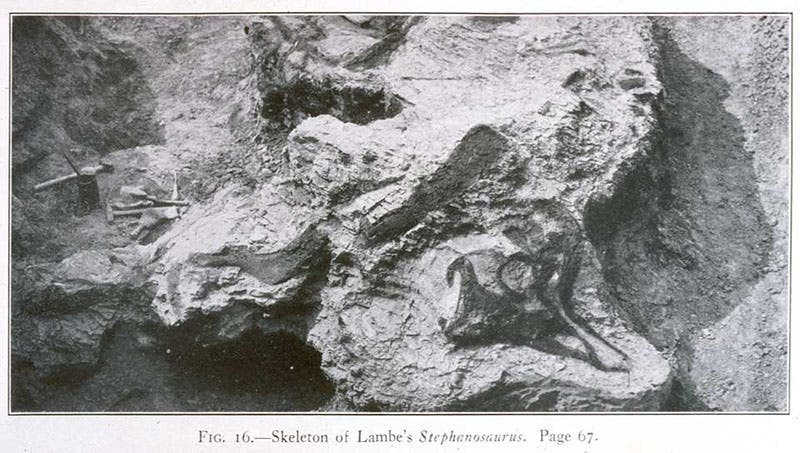

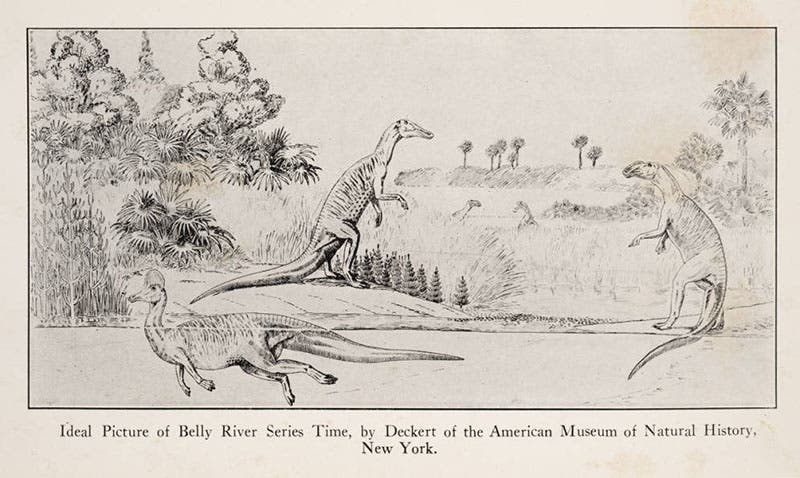

The fourth image shows a Corythosaurus skeleton before excavation had even begun, with the bones highlighted in the rock; the distinct crest from which it gets its name is unmistakable. We also include the frontispiece of the book (fifth image, above), since it is a pencil restoration of the environment at the Red Deer River at the time that dinosaurs lived there. Note that Corythosaurus is swimming, which Sternberg thought was its normal method of locomotion.

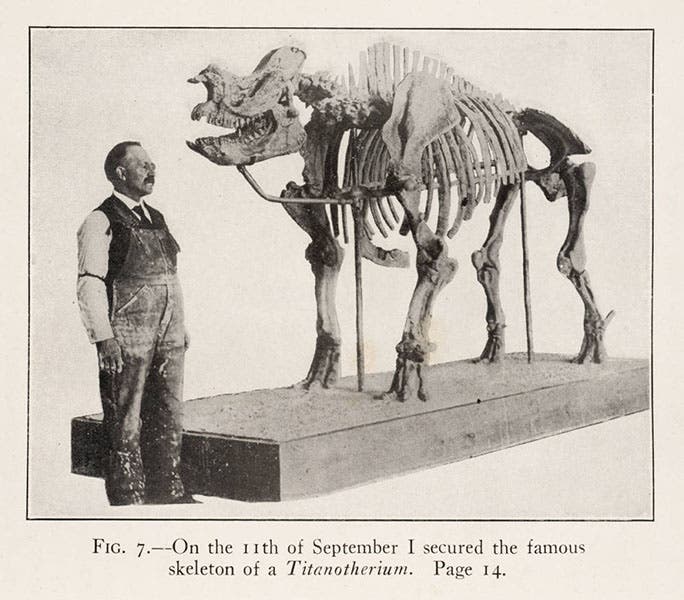

Finally, even though it is not a dinosaur, we show a Titanotherium skeleton that Sternberg discovered, primarily because Sternberg himself is in the photograph (sixth image, above). And we have a studio photo of his as well (seventh image, above)

The Sternberg Museum of Natural History, in Hays, Kansas (author’s photograph)

Sternberg spent the rest of his career in San Diego, and then retired to Toronto, living to the age of 93. There is a Sternberg Museum of Natural History several hours west of Kansas City, in Hays, Kansas. There are specimens there recovered by all four male members of the Sternberg family, including a famous “fish within a fish” discovered by son George. It is a pleasant place to stop on the way between Kansas City and Denver on I-70 (eighth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.