Scientist of the Day - Charles Green

Charles Green, an English aeronaut, was born Jan. 31, 1785. The Age of Ballooning began with the Montgolfier brothers' first successful balloon flights in 1783, and soon balloons were everywhere, either hot-air ballons, like those of the Montgolfiers', or hydrogen balloons, which were much more buoyant, but also much more dangerous, since they were highly inflammable. Green made his first ascent in 1821, when he was 36 years old, and he was hooked. He would make more balloon flights than anyone in the world before he gave up the pastime some 31 years, and over 500 ascents, later.

Green brought novelty to ballooning with his very first flight, for which he used coal-gas, rather than hydrogen as the lifting agent. Coal-gas was still an incendiary gas, being in large part hydrogen, with carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and methane mixed in. But coal-gas was much easier to generate than hydrogen; it took days to produce enough hydrogen to fill a balloon, and involved pouring sulfuric acid over iron filings, which was itself very dangerous, since it produced enormous amounts of heat as a by-product. The only drawback to coal-gas was that it produced much less lift than hydrogen. But with large balloons, that proved to be no problem.

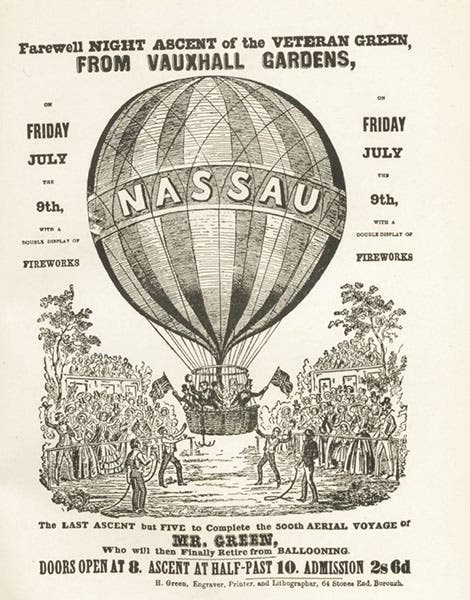

We skip over the first 15 years of Green's ballooning career to get to 1836, when Green persuaded Robert Holland, a wealthy friend and M.P., to sponsor an effort to set a long-distance ballooning record. No one seems to know what the record was before the Great Ascent of 1836, but we know what it was afterwards. The vehicle was a large balloon that Green had built for Vauxhall Gardens, a pleasure garden in south London.

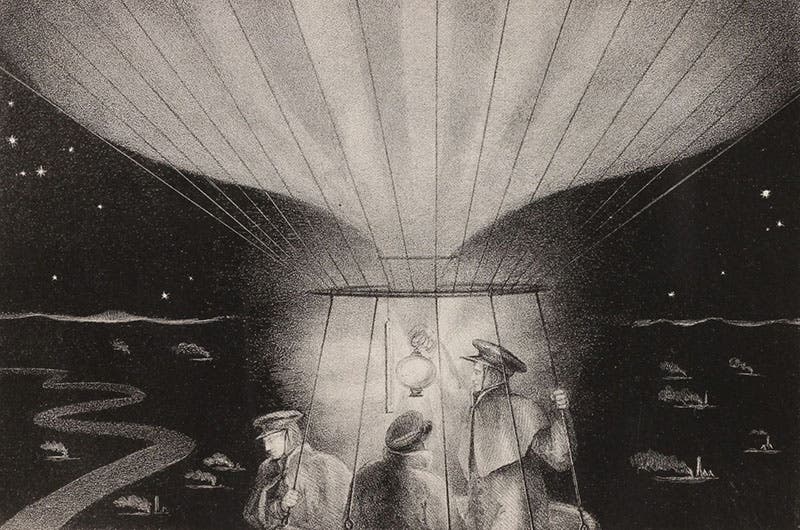

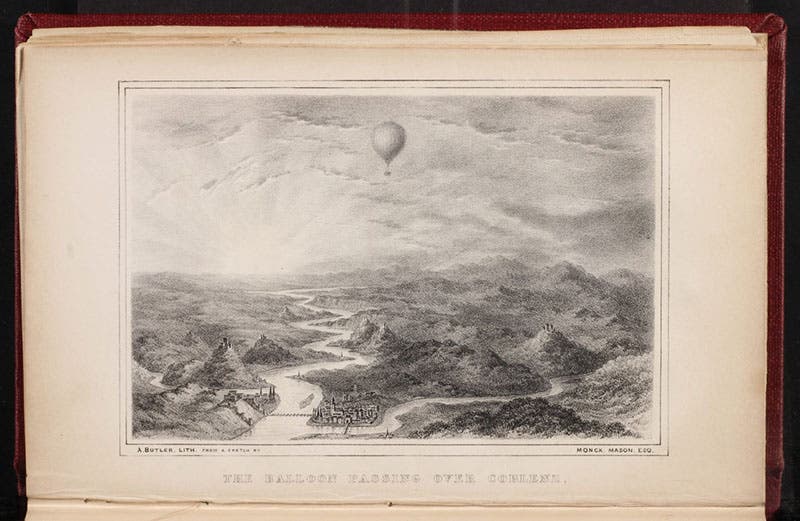

Vauxhall Gardens was williing to lend Green the balloon he had sold them for the flight, and also agreed to provide a venue for the ascent. The balloon was originally known as the Great Balloon, and then as the Vauxhall, and eventually the Nassau. For the ascent of Nov. 7, 1836, the wicker gondola contained three people: Green, Holland, and Monck Mason, a journalist. Balloons, unlike the later dirigibles, were unable to navigate, except for rising and sinking to find different wind patterns, and basically, they went where the prevailing winds took them. On this occasion, that direction was east-southeast. By dusk they were crossing the Channel, that night they passed over Liège in Belgium, and by the next morning, they saw the sun rise over Koblenz, landing shortly thereafter near Weiburg in Nassau. They aeronauts had travelled almost 500 miles in about 18 hours, which was considered a spectacular achievement at the time. They were fêted in Weiburg, and then again in Paris on the way home. The balloon was henceforth called the Nassau, after its landing spot in Germany.

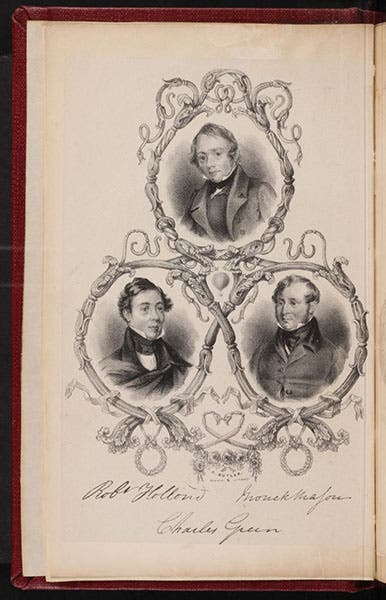

Mason soon wrote a short tract about the flight – that was why he was on board – and in 1838, he published an expanded illustrated book, called Aeronautica; or, Sketches Illustrative of the Theory and Practice of Aerostation, Comprising an Enlarged Account of the Late Aerial Expedition to Germany, which we have in our collections. This work has supplied several of our images, including the beautiful lithograph of nighttime over Liège (third image), a view of sunrise over Koblenz (fourth image), and the frontispiece portrait of the three aeronauts, with Green at top center and Mason at bottom right (fifth image).

About the same time as Mason's book appeared, John Collins completed a painting about the Vauxhall/Nassau adventure, usually titled: A Consultation Prior to a Flight to Germany, where Green is seated at right, Mason is standing behind him,and Hollond is seated opposite Green (sixth image). The painting is in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

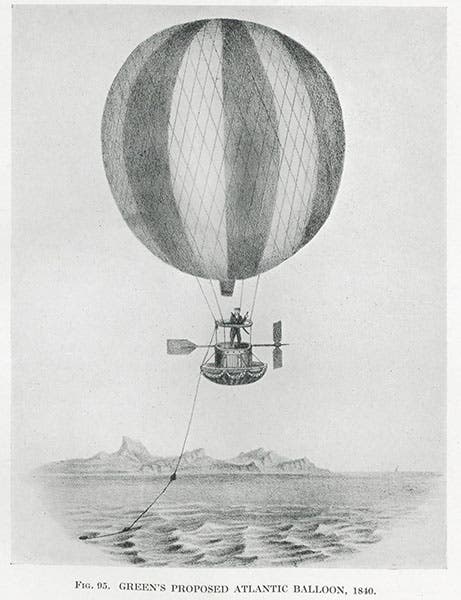

At the time of the 1836 flight, Green had made some 250 ascents. He would make that many more before he retired from ballooning in 1852. In 1840, he proposed a trans-Atlantic flight, and even designed (but did not build) a balloon for that purpose), with a small propeller to steer it. Four years later, Edgar Allan Poe, inspired perhaps by Mason's book and Green's proposal, published "Balloon-hoax" in the New York Sun (the same penny-daily that had published Richard Locke's "Moon Hoax" of 1835). Poe reported that Mason and Hollond and six others had successfully crossed the Atlantic Ocean in just three days in a giant steerable balloon, The Victoria. Interestingly, Green, the only actual balloonist of the famous trio, was left out of Poe's spoof. It is not clear if Poe understood that Green’s proposed crossing was from west to east, from New York to England, since that is the direction of the prevailing winds.

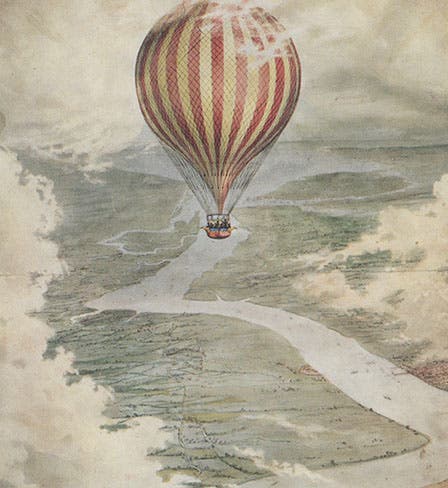

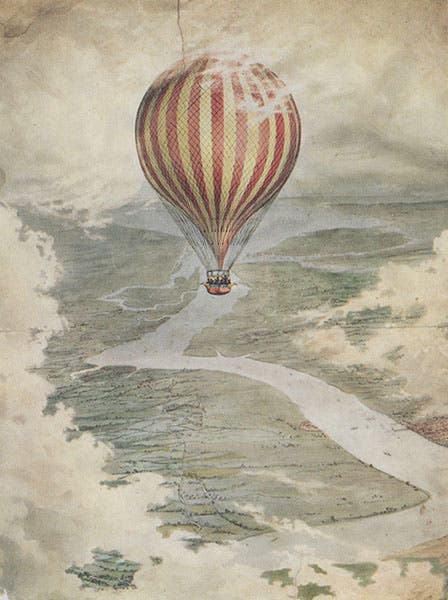

Green lived another 18 years after his retirement, passing away in 1870. In 1924, his career, and especially his Koblenz flight, was retold in a sumptuous, illustrated quarto about famous balloon adventures by British aeronauts: The History of Aeronautics in Great Britain, by John E. Hodgson, which we have in our collections. There is an entire chapter on Green, with many images reproduced from broadsides that had not previously appeared in book-form. The splashiest is a color gravure of the Vauxhall or Nassau over Medway in 1837 (first image). Other plates show Green’s proposed trans-Atlantic balloon (seventh image), and a broadside advertising Green’s 495th ascent from Vauxhall Gardens in 1852 (eighth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.