Scientist of the Day - Charles-François Exchaquet

Charles-François Exchaquet, a Swiss relief cartographer, foundry operator, and alpine climber, was born in Court in the Bernese Alps, on Dec. 6, 1746. He became interested in mountain climbing at a young age, since he grew up in the shadow of Mont Blanc, and in mineralogy, or more precisely, rock collecting. Sometime around 1780, he was appointed director of the Mines and Foundries of Haut-Faucigny, and soon was chosen to run an ore-processing plant and foundry in Servoz, near Chamonix, at the base of Mont Blanc. He helped found a scientific society in Lausanne in 1783, and his house in Servoz was a frequent stopping point for would-be alpinists who wanted to be the first to climb Mont Blanc, since Exchaquet knew the glacial valleys better than anyone. He met in this way Horace Bénédict de Saussure, who would succeed in climbing Mont Blanc in August of 1787, and Saussure was quite favorably impressed with Exchaquet’s knowledge of the Mont Blanc massif. Exchaquet would later accompany Saussure and his family on an overnight climb up one of the glacial valleys above Chamonix in pursuit of rock specimens.

Soon after Saussure’s successful ascent of Mont Blanc, Exchaquet produced a carved wooden relief of the Mont Blanc massif, which is usually called a “maquette,” although that term is more properly used for a preliminary wooden carving of a proposed marble sculpture. But we will conform to usage and employ the term here. Exchaquet’s maquette was about three feet long and two feet wide, and was carved from Swiss stone pine, a wood favored by Swiss woodcarvers. It was then painted, with the snow cover conforming to the conditions in August, climbing season. Where Exchaquet learned this craft, I have no idea. But he was clearly good at it, and more importantly, his wooden relief map was accurate – a climber could study it and figure out exactly what route he wanted to take to whatever summit. Exchaquet either made copies of his original maquette, or paid sculptors to copy it, for five of them survive today, and possibly others lie secluded in municipal basements in France and Switzerland. The two Mont Blanc maquettes of which I could find images are in Teylers Museum in Haarlem in the Netherlands (first image), and in a museum, presumably the Natural History Museum, in Geneva (second image). Exchaquet later made a similar wooden maquette of the Saint-Gotthard massif in central Switzerland; I was unable to locate an example or find an image. Since the original maquettes of Mont Blanc were expensive, Exchaquet commissioned smaller-scale copies in terracotta, some pocket-sized, that were more affordable.

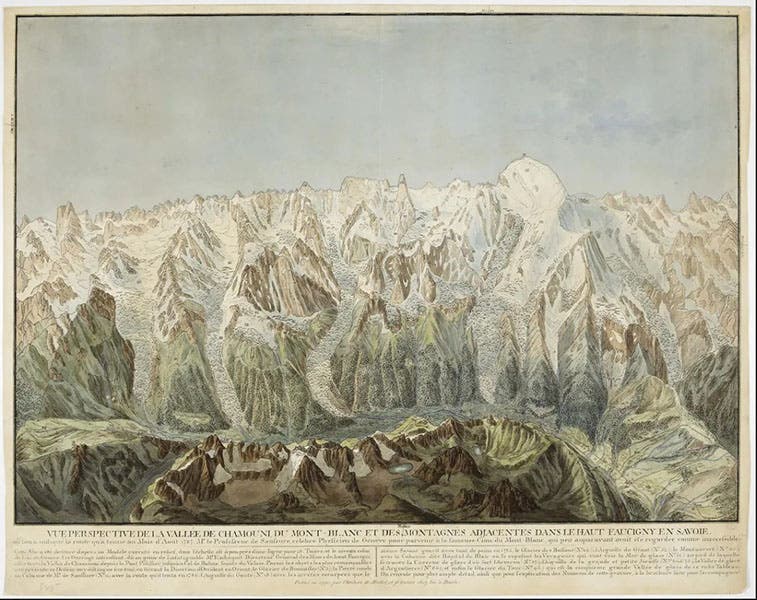

I find it interesting that several printers issued engravings of the Mont Blanc massif, made not from first-hand observation of the Chamonix valley, but from Exchaquet’s maquettes, complete with the red line that marked Saussure’s path to the summit of Mont Blanc (third image). Since Exchaquet’s wooden model thus became the basis for a finished work of art (the engraving), perhaps maquette is the right word after all.

We know little else about Exchaquet, except that his reputation as an alpine and mineralogical expert remained high until 1792, when he suddenly became quite ill; he recovered temporarily, but then collapsed and died in early December, 1792. He was only 46 years old. There does not seem to be a surviving portrait, nor a known gravesite.

Wooden models of geological terrains became popular in the 19th century; perhaps Exchaquet’s accurate maquettes of Mont Blanc were responsible. But they are very hard to find. If anyone knows the locations of any 19th-century wooden geological models in the United States, I would be grateful for the information.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.