Scientist of the Day - Charles Elton

Charles Elton, a British ecologist, died May 1, 1991, at age 91. In 1921, while a student at Oxford, Elton spent a summer on Spitsbergen, observing the interplay between polar bears, seals, and their prey. After several more summers on the Arctic island, Elton turned his observations into one of the seminal books of 20th-century animal ecology, titled, fittingly, Animal Ecology (1927). Here Elton set down a fundamental ecological dictum, that we should study animals, not in isolation, but as they fit into their environment, in what he called their "niche." The term niche had been used before, but primarily as a synonym for “habitat.” Elton gave niche a functional definition—it wasn’t so much where an animal lived, but how it lived, that determined its niche in nature.

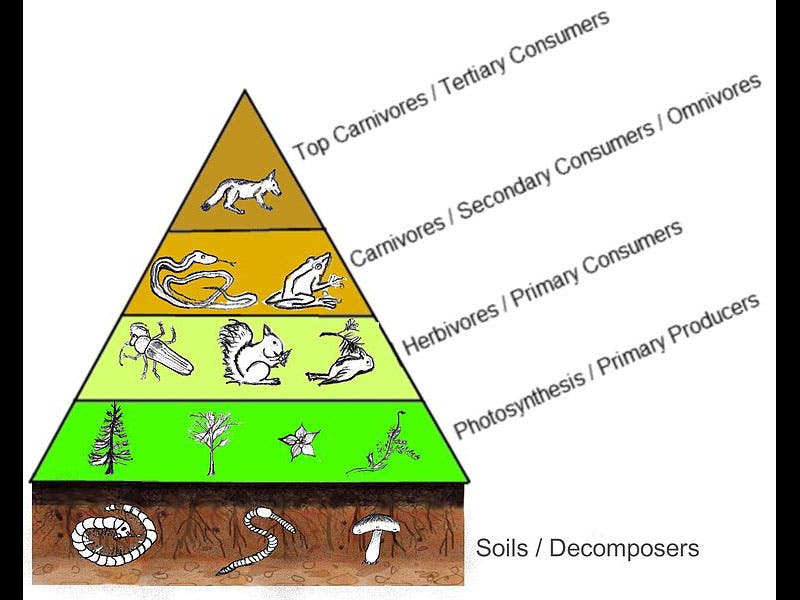

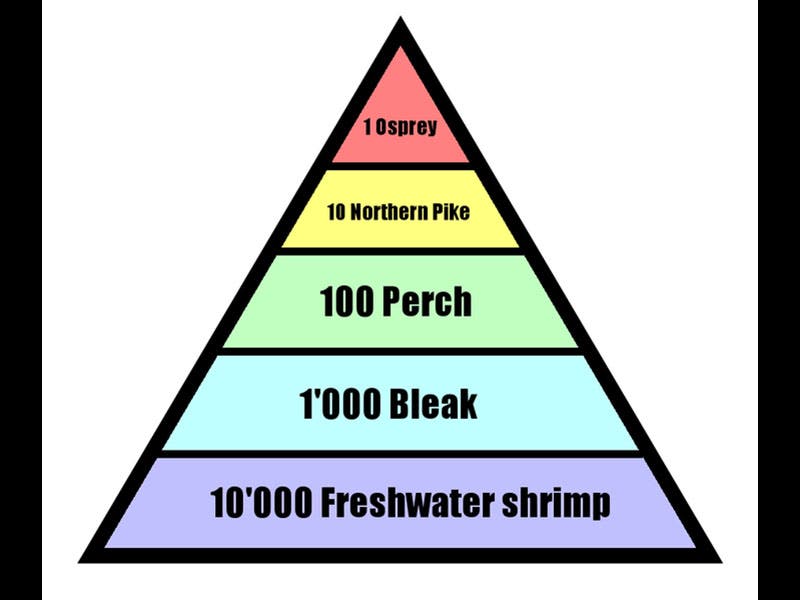

In addition to defining the idea of an ecological niche, Elton was the first to call attention to the importance of food chains, and to the "pyramid of numbers", which is how he referred to the fact that, in a typical food chain, there will be a large number of organisms at the bottom, a more modest group of first order consumers, a smaller number of second-order predators, and perhaps just one or two large predators at the top (see second and third images above). Each order of predators is significantly larger in size than the ones on which they feed, but considerably fewer in numbers. So tigers and great white sharks (and polar bears) are very scarce. The pyramid of numbers is often referred to today as the Eltonian pyramid. When Paul Colinvaux wrote an introduction to Eltonian ecology in 1978, he very appropriately called it: Why Big Fierce Animals Are Rare (1978). Almost 40 years later, it is still well worth reading.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City