Scientist of the Day - Charles Bonnet

Linda Hall Library

Charles Bonnet, a French naturalist living in Switzerland, was born Mar. 13, 1720. Bonnet is known for many important scientific discoveries, being the first, for example, to observe parthenogenesis in aphids, the bearing of young without male fertilization, a very exciting discovery at the time. But today we discuss his avid defense of the Great Chain of Being. It was a common belief in the 18th century that all natural entities could be arranged in a linear sequence without breaks, running from inanimate rocks and minerals up through plants and animals all the way to the top, which was, of course, us. The idea went back to Aristotle, but it really flowered in the 18th century, when so many new plants and animals were being discovered. Linnaeus believed in the Great Chain of Being and thought his taxonomy was a detailed explication of that order. Most adherents to the idea of the Great Chain were confident that there could be no gaps in the chain, or the whole concept would collapse, and hence they opposed the possibility of extinction, which would break the Chain.

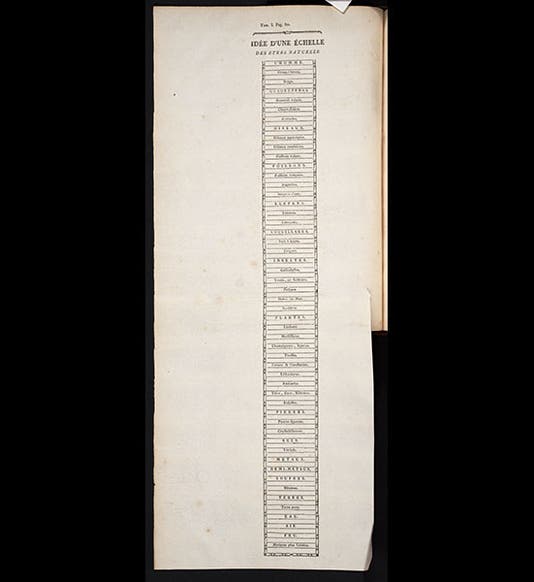

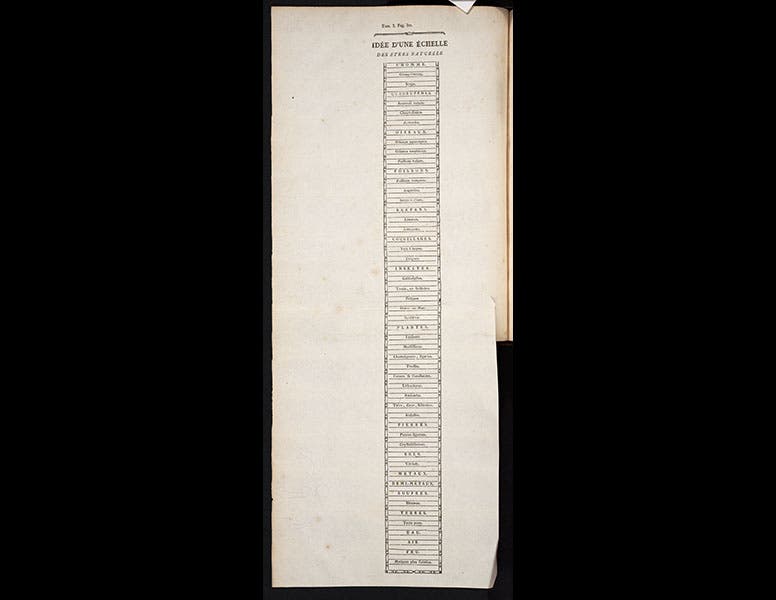

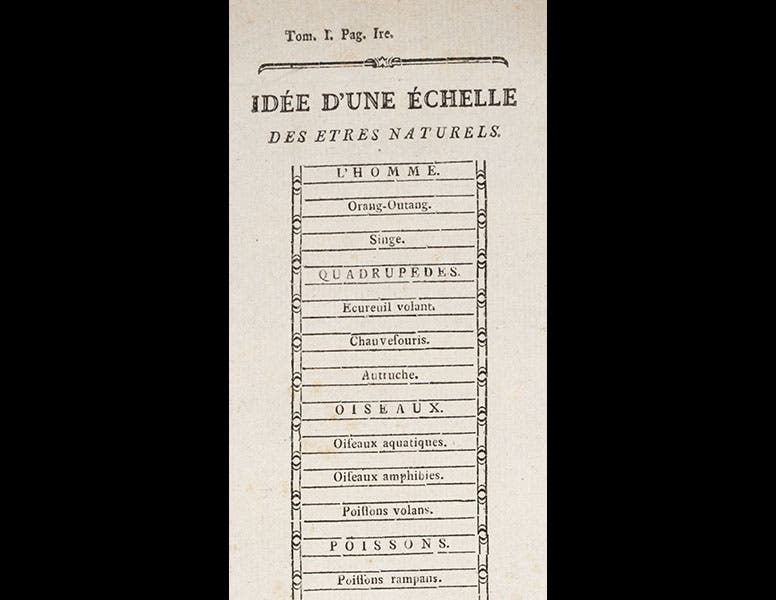

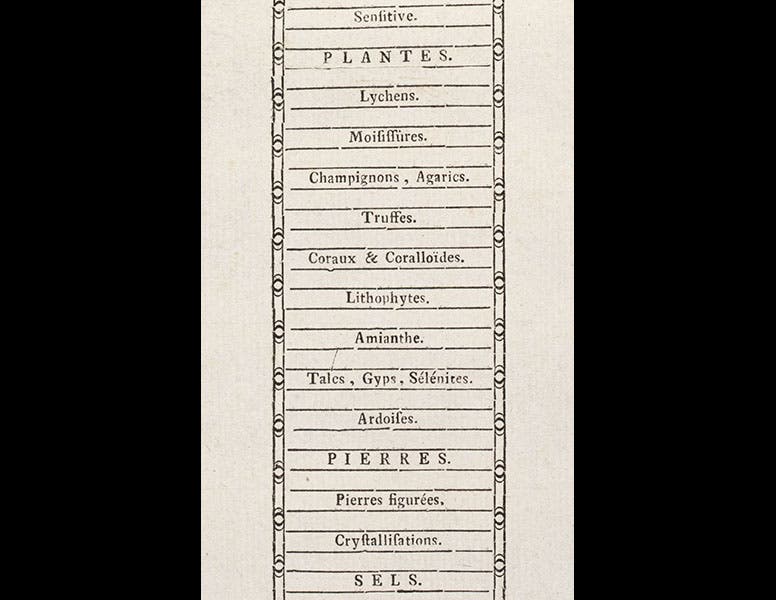

Bonnet, in his Contemplation de la nature (1764), not only defended the concept, but provided us with a graphic illustration, one of the very few images from the time of an actual Chain of Being. We have Bonnet's 8-volume Oeuvres (1779-83) in the History of Science Collection, and the chart appears there (first image). Notice how Bonnet was careful to fill the gaps between the major types of organisms. So between Man and Quadrupeds you have Orangutan and Ape; between Quadrupeds and Birds there is a Flying Squirrel, a Bat, and an Ostrich; and between Birds and Fish, Bonnet inserted Aquatic Birds, Amphibious Birds, and Flying Fish (fourth image). Similarly, Sensitive Plants come between Insects (the lowest animals) and Plants, while between Plants and Stones one finds Lithophytes, or dendrites, stones with plant-like markings (fifth image). It was, or seemed to be, a perfect plan for the created order.

Bonnet lost both his hearing and his sight before he was very old, but he survived and worked productively, with considerable help, until the age of 73.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.