Scientist of the Day - Cesare Cremonini

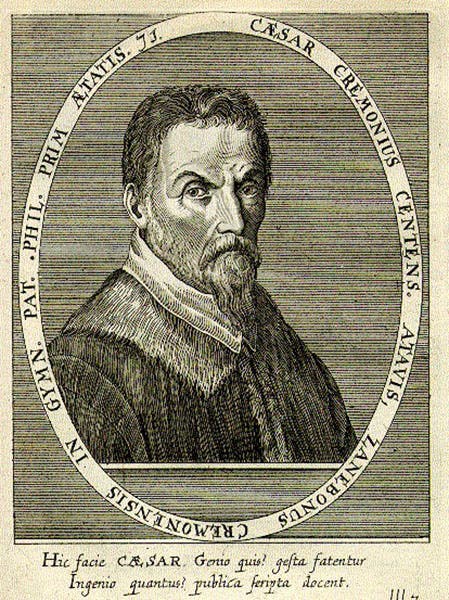

Cesare Cremonini, an Italian natural philosopher, died July 19, 1631, at the age of 81. Cremonini spent the first part of his career at the University of Ferrara, where he had the patronage of the Este family of Ferrara. In 1591, he moved to the University of Padua, where he was appointed to succeed Jacopo Zabarella. Cremoni would teach natural philosophy at Padua for the rest of his days.

One year after Cremonini arrived at Padua, a much younger man, Galileo Galilei, was appointed to the chair of mathematics (at a salary only a fraction of what Cremonini received). Galileo would spend his life arguing that a good natural philosopher should be a mathematician. Cremonini would insist that a good philosopher should be, above all, an Aristotelian.

There were various kinds of Aristotelians in Italy at the turn of the 17th century. Many of the doctrines of Aristotle, such as his belief in the eternity of the world, were contrary to Christian ideas, so often one had to choose between Aristotle and Christian dogma. Cremonini had what we call an Averroistic lean, preferring Aristotle to, say, Augustine, or Thomas Aquinas. So when Aristotle taught that only the rational soul, a kind of shared cosmic soul, is eternal, and that our personal soul perishes at death, Cremonini was inclined to accept the Aristotelian interpretation, although it seems he agonized over this quite a bit. Still, he was continually being investigated by church authorities, and it was only his ties to Venice, Padua’s home city and no friend of Rome, that protected him from the Inquisition.

Galileo and Cremonini seem to have gotten along well at Padua until 1604, when a new star in the heavens led Galileo to give a series of public lectures on the nova, and to suggest that Aristotle was wrong about the immutability of the heavens. This did not sit well with Cremonini, who was not about to relinquish a tenet of Aristotelian cosmology on such flimsy evidence.

Galileo left Padua for Florence in 1610, which Cremonini saw as a kind of betrayal, since it brought Galileo closer to both Romans and Jesuits, the latter having recently been evicted by the Venetians from their city. Galileo’s discovery in January of 1610 of the moons of Jupiter, which he named after the Medici family of Florence, is what brought the new job offer. It was reported at the time that Galileo offered to let Cremonini look through his telescope and see for himself that the Moon is blemished and pockmarked, contrary to Aristotle’s teaching that the Moon is a perfect celestial body. Cremonini supposedly refused the offer, because he knew that Aristotle could not be wrong about such a matter. I am not convinced this happened for that reason, but many biographers seem to accept the story as historical fact, and so Cremonini has come to represent blind adherence to authority that fails to be swayed by reason and experience. Others have noted that Cremonini did look through a telescope and could see nothing with it (many observers had that problem with the first telescopes), and so his refusal of a further offer is not all that surprising.

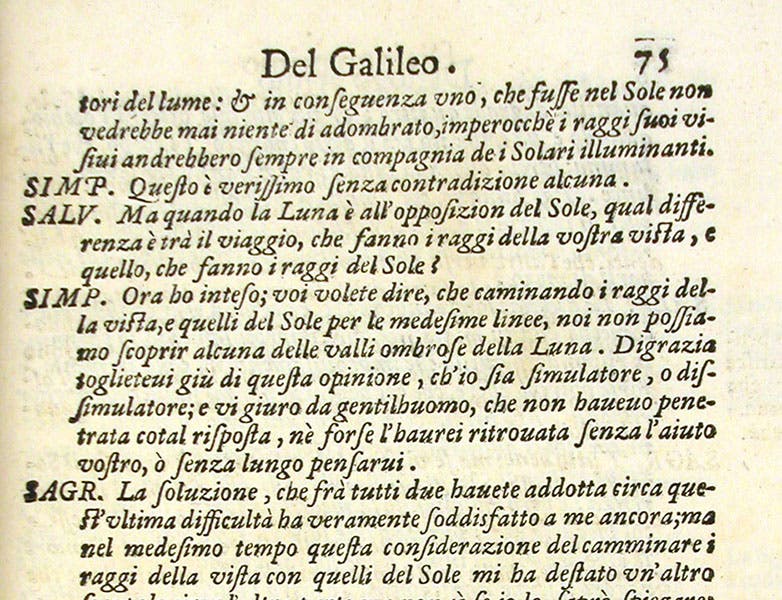

It has also often been suggested that Cremonini appears as a character in Galileo’s Dialogo … sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems, 1632). This book, presenting the arguments for and against the heliocentric system of Copernicus, is written in the form of a dialogue between three interlocutors (third image). Two of them, Salviati and Sagredo, who represent the Copernican and the neutral questioner, are named after friends of Galileo. The third, who represents a traditional Aristotelian, is named Simplicio (the simpleton), and it is said that Galileo took his model for Simplicio from Cremonini, and the words and arguments of Simplicio primarily from the teachings of Cremonini. This is possible – by 1631, Cremonini had written his own De caelo (On the heavens) without mentioning Galilo or the telescope – but it is more likely that Simplicio is an amalgam of all the Aristotelian opponents Galileo had wrangled with over the decades, and there were many. Nevertheless, Cremonini, perhaps unfairly, has come to be the iconic representative of reactionary academic Aristotelianism, stubbornly resisting the fruits of mathematical and experimental science.

That said, there is another piece of evidence that might be offered in the court of judgment. Some of you know that I am a long-time student of 17th-century engraved title pages and frontispieces, and so I show you here a detail of the frontispiece to Galileo’s Dialogo, which depicts three figures, who represent (the labels tell us, reading left to right): Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Copernicus. It has been often noticed that the Copernicus figure looks nothing like Copernicus, but does closely resemble Galileo, as perhaps a way of saying that Galileo takes the side of Copernicus in the debate over world systems. But no one has ever wondered in print (to my knowledge) who might have influenced the depiction of Aristotle. We wrote a post three days ago on the representation of Aristotle in the 17th century and observed that he was usually shown as young and beardless. The Aristotle that della Bella portrayed is hardly that. Whom might he have used for his model? Well, if you look at the two portraits of Cremonini that we have (both showing him in his forties), and age him 35 years, so that he is now bald, but still with the long, pointy, chin-beard, then he might not look much different from the figure on the frontispiece. The prosecution rests.

We have nothing by Cremonini in our collections. It would be nice to acquire his Disputatio de caelo (1613-16).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.