Scientist of the Day - Cesar-Francois Cassini de Thury

César-François Cassini de Thury, a French astronomer and cartographer, was born June 17, 1714. Cassini was a member of one of the very few family dynasties in science. His grandfather was Giovanni Domenico Cassini, who came to France from Italy in 1669 to supervise the building of the Paris Observatory, and who discovered four new moons of Saturn and the division in its ring. We profiled grandfather Cassini just over a week ago (here is that post).

César's father was Jacques Cassini, who succeeded Giovanni as head of the Paris Observatory and did important geodetic work, extending the length of the meridian that ran through Paris. César in turn had a son, Jean-Dominique, who succeeded him as head of the Paris Observatory and continued his ancestors’ attempts to determine meridians and parallels with ever greater precision. It is common to refer to the four Cassinis as Cassini I (Giovanni Domenico), Cassini II (Jacques), Cassini III (today’s subject, César-François), and Cassini IV (the great grandson, Jean-Dominique). The only scientific dynasty to rival the Cassinis were the Bernoullis of Switzerland, which produced four brilliant mathematicians, father and son, brother and nephew. But the Bernoullis are never referred to by roman numerals.

Geodesy is the science of measuring the Earth, usually for the purpose of mapping, but in 18th-century France, with the additional goal of determining the exact shape of the Earth. It involved laying out large triangles on the Earth’s surface, using precision rods to construct one side of the first triangle (the baseline), and then employing optical sighting to determine the other two sides, the bases for further triangles. Regular measurement of the altitude of stars was necessary to correlate the distance measured in feet and rods with the distance in degrees. The basic reference line in French geodesy was the Paris meridian, the north-south line that runs right down the middle of the Paris Observatory. Geodesy in France began with Jean Picard and continued with the entire Cassini family.

César’s father Jacques devoted his life to geodesy, and he was convinced that his careful measurements of the length of a degree at two different locations along the Paris meridian showed that the Earth was not spherical, nor onion-shaped (oblate), as the Newtonians across the channel maintained, but rather lemon-shaped (prolate), as his father Giovanni Domenico had argued, following René Descartes.

Pursuing his own geodetic measurements, César had initially followed his father and grandfather in defending a prolate Earth, but he gradually came to realize that the margin of error in his father’s measurements was actually greater than the differences in distance that his father had claimed to have detected, so in a real sense, he had not proved anything at all. César’s own measurements gradually convinced him that the Newtonians were correct, and the Earth is flattened at the poles, and he officially joined the heretics in a book, La meridienne de l'observatoire Royal de Paris (1744), abandoning the family tradition of an elongated Earth. By that time, a geodetic expedition to Lapland, sponsored by the Paris Academy of Sciences, had shown conclusively that the Earth flattens as one goes north (you can read about the Lapland geodetic expedition in our posts on Alexis Clairaut and Abbé Réginald Outhier).

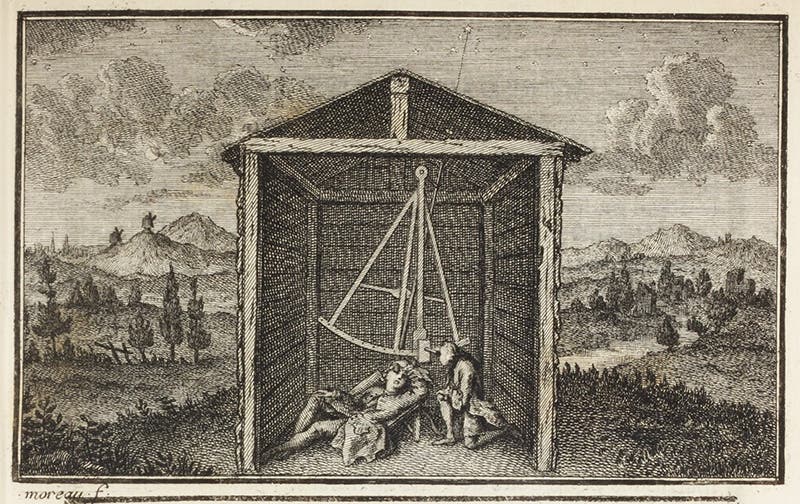

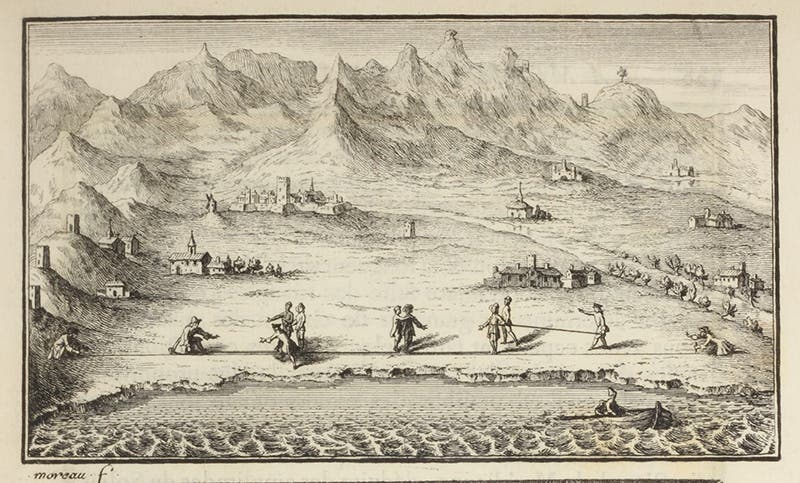

Cassini de Thury’s 1744 book, the only work by him in our collections, is well printed, with handsome engraved headpieces that illustrate the process of triangulation. We show three of them here, one a full-page shot, so you can appreciate why such an engraving is called a headpiece, and the other two in detail, so you can better see what is being depicted. The one shown full-page, and hence hard to make out, illustrates how one takes a sighting from a height on a distant point (third image). The fourth image shows the process of measuring the position of a star crossing the zenith at night, for the purpose of determining latitude. The third headpiece (sixth image) illustrates how precision rods were laid out end to end to establish the baseline. The French were particularly keen on the use of informative (rather than merely decorative) headpieces in this period, and we have reproduced quite a few of them in this series, including our posts on Pierre Varignon and Abraham Trembley. You can see the often-reproduced headpiece showing the Paris Observatory, from a 1740 book by Jacques Cassini, in our post on Giovanni Domenico Cassini.

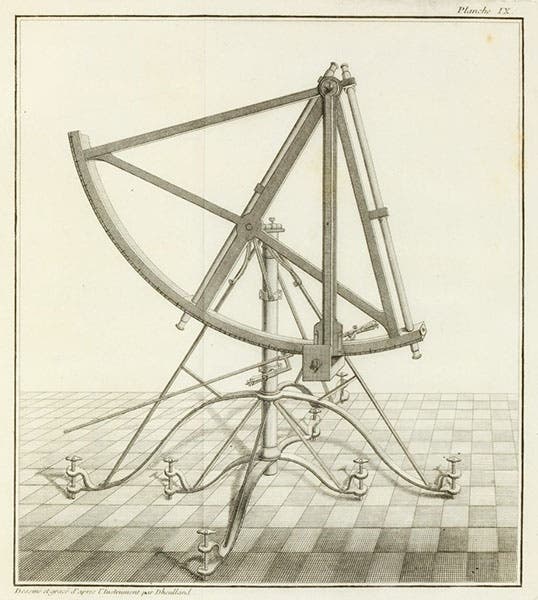

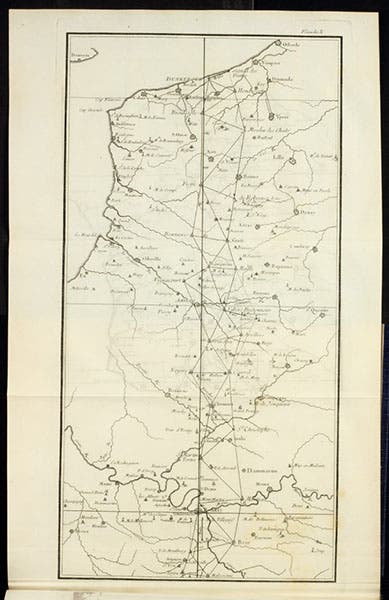

In addition to the handsome headpieces, and a plate showing a quadrant (fifth image), La meridienne de l'observatoire Royal de Paris also has a map of the complete Paris meridian, divided into two folding engravings. We show the plate with the northern half, from Paris to Dunkirk (seventh image), and then a detail of that half, from Paris to Clermont, so you can better see the details of the triangulations (eighth image).

César was apparently a mediocre astronomer, but he was good at geodesy, and superb at mapping. He constructed several maps of France, encouraged by the King, the last at a scale of 1:86,400, which means it required 182 sheets of paper. Apparently nearly all of it was competed by the time of his death in 1785, but we have nothing about his cartographic work in our collections, so while I know the map was completed by Cassini IV, I do not know if it was indeed printed.

The only portrait of Cassini III that I know of is in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, a miniature attributed to Jean-Marc Nattier (first image). But a note on the Museum’s webpage says that recently the identity of both the sitter and the artist have been called into question. We will continue to assume it depicts C�ésar until proved otherwise.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu