Scientist of the Day - Carl Linnaeus

Carl von Linné, a Swedish botanist and taxonomist better known as Carl Linnaeus, was born May 23, 1707. Linnaeus is one of the more familiar names in natural history, because he developed a taxonomic system for animals, in which they are divided, successively, into classes, orders, genera, and species, and because he proposed a binomial nomenclature system in which an animal or plant is identified by a two-part name, in Latin, drawn from its generic and specific names, as in Echinus europaeus (hedgehog) or Aquilegia canadensis (wild columbine). Both the taxonomic and the nomenclature systems were accepted by naturalists around the world and are still in use. We wrote a post on Linnaeus 7 years ago, discussing briefly his innovations in animal taxonomy and nomenclature, but we did not talk about the Linnaean taxonomic system for plants, which was quite different from that for animals.

It is not easy to discover a straightforward system for classifying plants. One is tempted to divide them into grasses, small flowering plants and herbs, shrubs, and trees, and then subdivide the flowers by color, or number of petals, but nothing really works. With animals, if seems intuitive that squirrels, beavers, and field mice belong together (in the order Rodentia), but it is not so obvious that tomatoes, petunias, and morning glories should be grouped together. Naturalists before Linnaeus tried many systems, sometimes just resorting to an alphabetical order in their herbals and florilegia.

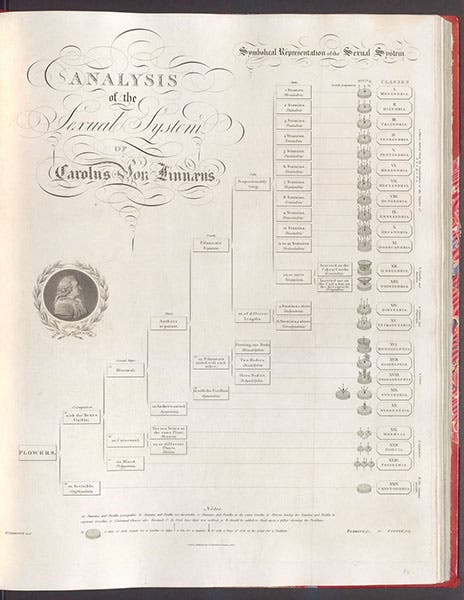

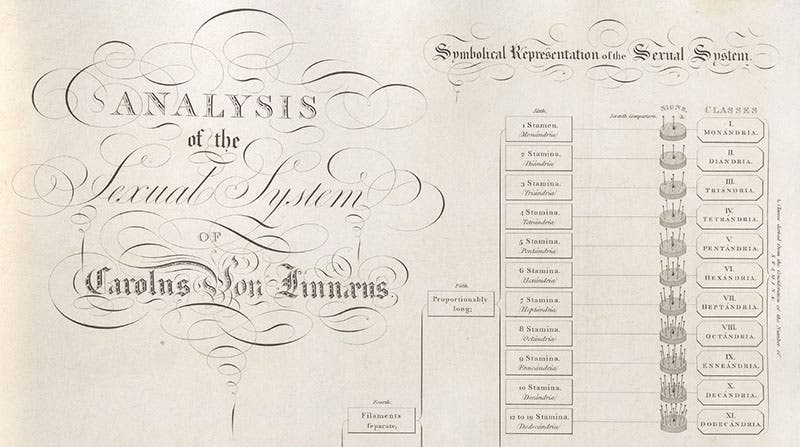

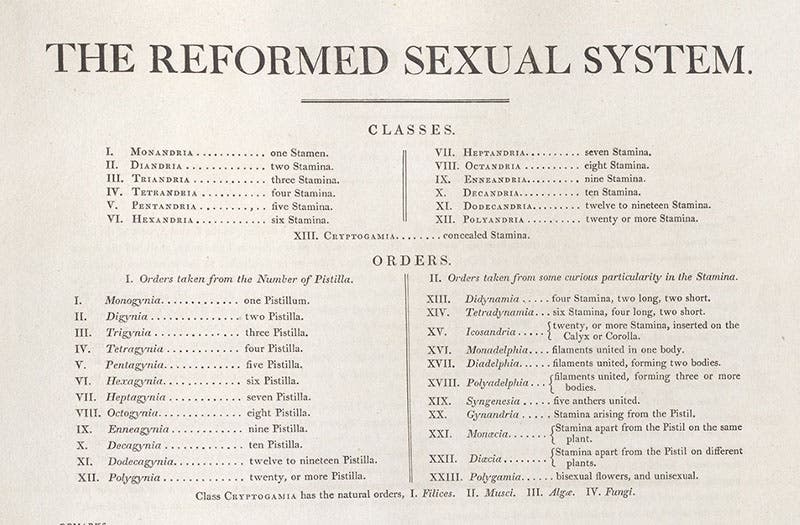

Since Linnaeus was unable to find a natural system of plant taxonomy, he decided on a system that he recognized as artificial – that is, not based on nature. He decided to group the plants into a number of different classes, depending on how many stamens there were in the flower. To divide the classes into orders, he relied on the number of pistils in the male flower. The plant classes had names like Monandria (one stamen), Diandria (two stamens), Triandria (three stamens), etc. The orders were named Monogynia (one pistil), Digynia (two pistils), and so forth.

This seems to be, on first confrontation, an absurd system, since two plants whose flowers have 7 stamens each might have nothing else in common. It is a completely artificial alliance. Yet there is one real advantage: The Linnaean plant system makes it easy to classify a newly discovered plant (and the number of new plants coming into Europe at that time was prodigious). A naturalist simply counts stamens and pistils, and he is already down to the family level. Then the naming can proceed according to the system of binomial nomenclature. It is an ideal system for the field botanist, even if it is arbitrary. Linnaeus’s “disciples” loved it.

Everyone agreed that a natural system would be better, but until someone could figure out what that might be, the Linnaean system was the system of choice. It was usually called the “Sexual System”, since it was based on the plant’s reproductive organs, and for that reason it came in for some criticism from the general public. Plant sexuality was a recent discovery, and people were trying to get used to that – it seemed a bit much to make it the basis for a taxonomy. But botanists had no qualms there – they liked not having to deal with plants on the class and order level, allowing them to concentrate on coming up with a good Linnean binomial name.

Linnaeus’s sexual system was developed and applied in his Species plantarum (1753), a book that we do not have in our collections (although the system is further developed in the tenth edition of his Systema naturae (1758, vol. 2, which we do have). But many later naturalists wrote books on the Linnaean sexual system for plants, and we illustrate today’s post from one of the most impressive plant volumes in our collection, New Illustration of the Sexual System of Carolus von Linnaeus, by John Thornton (1807). This book is often referred to as Thornton’s Temple of Flora, since that is the subtitle of the last half of the book, and that is what everyone wants to look at, with its glorious folio-size hand-colored prints of flowering plants. Indeed, we have written a post on Thornton, where we called the book Temple of Flora, and where you can see 4 of the splendid engravings. We have also written a post on Philip Reinagle, one of Thornton’s artists, where you can see 7 more images.

But the main title page of the book (second image), has the Temple of Flora in small type, and the Sexual System of Linnaeus in a very large font. The book was published to disseminate the Linnaean botanical system, and most of the text is devoted to explaining and defending it. There is a large engraved chart of the botanical classes proposed by Linnaeus; we offer here the entire plate, and a detail of the top, where you can read the names of the first 11 classes (third and fourth images). Thornton also had some suggestions on how to improve it, and we show you a chart of his “reformed” sexual system, mainly because it includes the orders, based on the number of pistils in the male flower (sixth image).

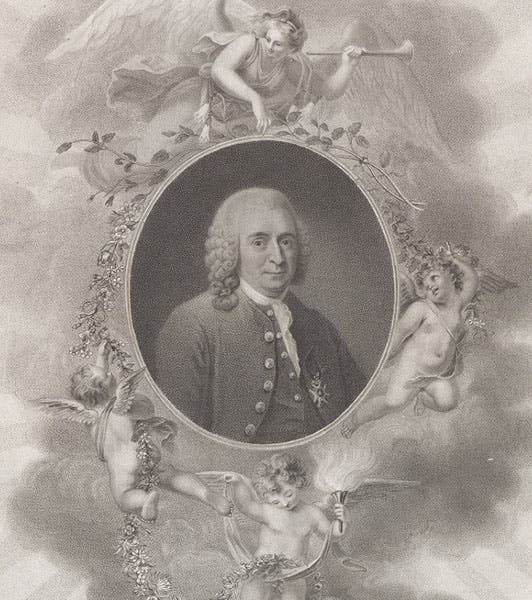

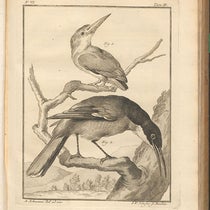

The book also includes, as a kind of bonus, three portraits of Linnaeus: one a bust, where he is colorfully surrounded by mythological figures such as Flora and Ceres (first image); another, a portrait medallion of an older Linnaeus, on a large page that we cropped down for the occasion (fifth image); and a third, a full portrait of Linnaeus in “Lapland dress,” engraved in mezzotint (seventh image).

We have several other books in our collections that promote and illustrate the sexual system of Linnaeus, such as Thirty-eight Plates, with Explanations: Intended to Illustrate Linnaeus's System of Vegetables (1799), by Thomas Martyn, and The Botanic Garden; a Poem, in Two Parts. Part I. Containing The Economy of Vegetation. Part II. The Loves of the Plants (1791) by Erasmus Darwin. In our posts on both botanists, we focused on the plates, rather than the sexual system theme that runs through both books, so we might return to them at some future time.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.