Scientist of the Day - Carl Anderson

Carl David Anderson, an American experimental physicist, was born Sep. 3, 1905, in New York City. He did his undergraduate work at Caltech in Pasadena, where Robert Millikan had built the boat and ran the ship. Anderson stayed on to do his PhD work under Millikan, who at the time (1930) was interested in cosmic rays. The fact that highly energetic particles rain in on us from outer space had been discovered by an Austrian, Victor Hess, in 1912, but no one much followed up on his work, until Millikan in the late 1920s chose to do so. Millikan also gave the rain of particles the name “cosmic rays,” the term we still use.

Millikan had three teams of graduate students investigating cosmic rays with different apparatus, such as Geiger counters and electroscopes. Anderson chose, or was assigned, to build a cloud chamber for studying cosmic rays. The cloud chamber had been invented by an Englishman, C.T.R. Wilson, also in 1912. It was a clever device that could be filled with a saturated vapor and was equipped with a glass window on one side, for viewing and photographing, and a piston, that could be suddenly withdrawn, causing the vapor to condense. If a subatomic particle should be passing through at the time, droplets condensed on the path of the particle, forming a visible track. It was like an aquarium for viewing particles we could not otherwise see, and it was a great boon to particle physicists.

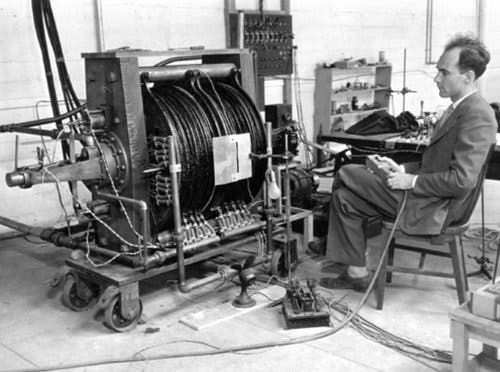

Anderson built a cloud chamber and equipped it with a large electromagnet that would curve the particle paths (protons bend one way, electrons another). Anderson installed it on the top of the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory, which had been built in 1929 to lure Theodore von Kármán to Caltech (the bait worked), and which had plenty of power to energize the electromagnets.

Anderson observed all kind of particle interactions, generated by cosmic waves, in his cloud chamber. There were plenty of electrons that left tracks, curved in response to the magnetic field. It seemed to Anderson that sometimes these electron-sized particles curved the wrong way, as if they had a positive charge. But it was hard to know, since an electron coming in from above would curve one way, and one from below the other, even though they both had a negative charge. You needed to be able to determine the direction of origin before you could determine whether it was bending right or left.

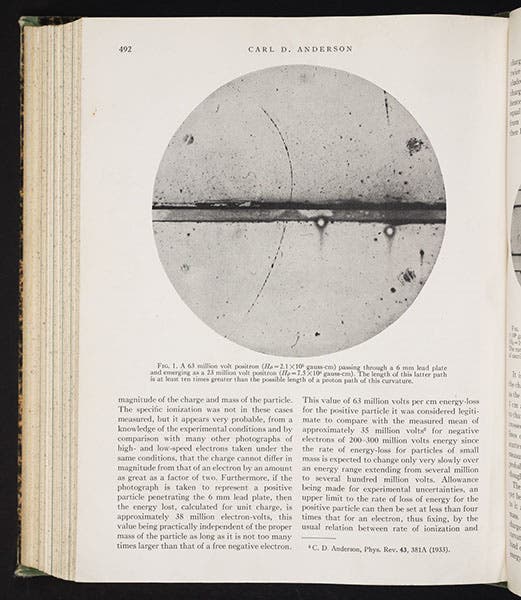

In 1932, Anderson designed a crucial experiment, just as Isaac Newton had 265 years earlier when studying light broken up by a prism. Anderson inserted a thin lead plate into his cloud chamber. A particle passing through the cloud chamber would have to go through the lead plate, and in doing so, it would lose energy and slow down, and its curvature would increase. So now you could tell whether the particle was coming from the top or the bottom, and its direction of curvature would now tell you whether it was positive or negative. A dramatic photograph was taken in 1932, recording a particle coming from the bottom and curving to the left, indicating a positive charge (third image, above). Yet it had the mass of an electron. So this was a new kind of particle, a positive electron, or a positron. Paul Dirac, 5 years earlier, had predicted the existence of antimatter – positive electrons and negative protons – which would have the potential to create anti-atoms. Anderson did not know of Dirac’s prediction. But he had discovered the first evidence of antimatter, created by energetic cosmic rays that could produce electron-positron pairs which then vanished in a burst of radiation. For his discovery of the positron, Anderson received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1936. He was 31 years old at the time, the youngest Nobelist in Physics ever. He shared the prize with Victor Hess, a nice touch by the Nobel committee.

Positrons are now real enough that there is a medical scanning procedure called Positron Emission Tomography (PET), during which radioactive tracers in the body emit positrons which quickly are annihilated, releasing gamma rays that can be detected and pinpointed. However, Star Trek notwithstanding, we still have not yet figured out a way to collect enough anti-matter to use it for a rocket-propulsion system.

Anderson spent his entire career at Caltech. He never much enjoyed the limelight that goes along with a Nobel Prize. But he did attend a function at the White House in 1962 to honor all living American Nobel Prize winners, where President Kennedy uttered one of his most memorable observations, saying, by way of introduction, "I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.”

I could not find Anderson in the official photo of the event (fifth image), because I do not know how tall he was, but perhaps you can, using the photograph above of an older Carl Anderson (fourth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.