Scientist of the Day - Buckaroo Banzai

On Aug. 15, 1984, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension premiered on screens across the country, making today the 35th anniversary of the release of that science fiction classic. This is one of my favorite SF films, although I would appear to be very much in the minority here, for reasons unfathomable. Part of the film’s attraction lies in the scientific premise (yes, it actually has one, unlike most SF movies) that if matter is mostly empty space, then two solid objects ought to be able to pass through one another. That possibility in turn gives rise to the suggestion that, at the moment of intersection, other dimensions with alien occupants might be encountered. The film also explores the possibility that the famous 1938 Halloween broadcast by Orson Wells witnessing a Martian invasion at Grovers Mill, New Jersey, was not a hoax after all. Instead, it described a true alien encounter that was later proclaimed a hoax for security reasons. The aliens (called Red Lectroids) are right now (1984) preparing to return to their planet, as their leader breaks out of the Trenton Home for the Criminally Insane, and the plot is off and running.

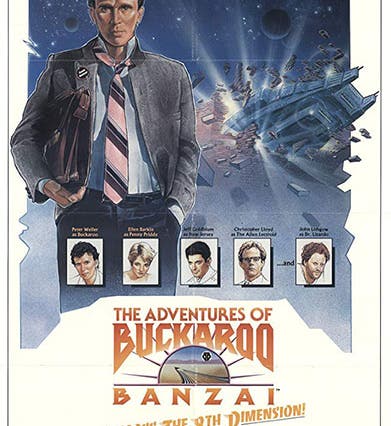

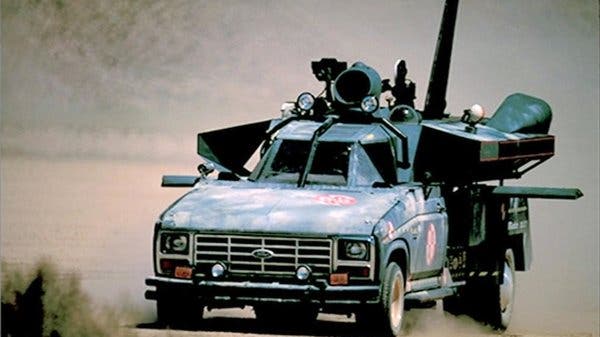

Buckaroo Banzai’s jet car, with which he drove through a mountain, with the help of his oscillation overthruster (tested.com)

Another attraction of the film is the cast, starting with Peter Weller in by far his best film role as Buckaroo Banzai – physicist, brain surgeon, rock band leader, and interpenetrator of matter with his jet car (second image) and his “oscillation overthruster”, the device that allows him to drive through a mountain (third image). Add in John Lithgow as the leader of the Red Lectroids, who gives a wonderfully manic performance as an alien with a Mussolini complex, Ellen Barkin as the femme fatale, Jeff Goldblum, Christopher Lloyd, Robert Ito, Jonathan Banks, and a host of little-known but gifted actors who play Banzai sidekicks (and members of Buckaroo’s band, The Hong Kong Cavaliers), and you have a totally charming cast ensemble. Plus, the film has great music – the first tune belted out by Banzai's band is "Rocket 88", often considered to be the very first rock-and-roll song (1951; Buckaroo's jet car in the film has "Rokit88" for a license plate), which is followed (after Ellen Barkin's character in the club audience tries to shoot herself) by one of the all-time great love-lost ballads, "Since I don't have you" (The Skyliners, 1958).

The film also has many quotable lines, an essential for any movie before it can be called a classic or even a cult-classic. When Buckaroo is admonishing the club audience, who is booing the tale of woe of Penny Priddy (Barkin's character), he says: "Remember, no matter where you go ... there you are." When the manager of the Trenton Home (played by Banks) jokes at the claim of Emilio Lizardo alias John Whorfin (Lithgow's character) that he is leaving tomorrow, Lizardo replies: "Laugh while you can, monkey-boy." There are many more such tidbits: “Why is there a watermelon there?”, as Goldblum’s character encounters a melon in a hydraulic press, or “Hey man, nice jacket. What’s in the big pink box?” (too complicated to explain here, but if you see the film, you will remember it).

And the script has an off-beat sense of humor that I, at least, find amusing. After the alien Red Lectroids first landed in New Jersey in 1938, the next day they all applied for social security numbers, taking American names, and every prename was John, with assorted surnames like John Whorfin, John Small Berries, John Ya Ya, John Many Jars, and John Bigbooté. I also like the alien space ships, which the production designers realized as giant pieces of driftwood, with lifeboats shaped like ginger roots (fifth image). Why, after all, should alien ships look like our spacecraft, or like flying saucers? And you have to love the eye shields worn by Buckaroo’s crew when viewing a hologram, made from crudely-scissored bubblewrap. The final scene, where Lizardo/Whorfin/Lithgow is trying to escape in his reconstructed spaceship/mandrake root, which has foot controls over which Lithgow’s bare feet dance wildly, like some mad organist, is a fittingly farcical ending to this improbably entertaining film. If you haven’t seen the movie, give it a whirl, and if you don’t like it, tell me why. There has to be a reason why W.D. Richter, the director, has yet to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Motion Picture Academy.

The closing credits for the film are somewhat notorious, since they make no sense at all, as we see Buckaroo walking swiftly down a dry Los Angeles sluiceway, where he is joined one by one by his cast mates, some risen from the dead. When they filmed the sequence, they used Billy Joel’s “Uptown Girl” as the marching music, but as they were out of money by the end of production and could no longer afford the rights, the film composer, Michael Boddicker, had to write an original piece of music with the same lilt and tempo, and he was certainly up to the task. The tune really puts you in a good mood, if you happen to be leaving the theater afterwards, or if you just need a general pick-me-up. So no matter where you are, here you go!

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.