Scientist of the Day - Boris Pash

Boris Pash, an American Army officer of Russian descent, was born June 20, 1900. Pash rather coasted through his first 40 years of life, teaching school and coaching baseball in a Hollywood high school, but he did get a master’s degree in science education, and he did join the Army Reserve and qualify as an intelligence officer. When World War 2 began, he was called up and quickly moved up the ranks. He was assigned to the San Francisco Intelligence Office, and was asked to investigate the staff at Berkeley's Radiation Laboratory, where a Russian leak was suspected. This investigation included Robert Oppenheimer, who was running the Manhattan Project; Pash concluded that Oppenheimer was or had been a communist but was unlikely to be a spy.

General Leslie Groves, military leader of the Manhattan Project, must have liked Pash's work, for when concerns arose in1943 that the Germans might be developing nuclear weapons of their own, it was decided to field a small task force to go to Europe to investigate, and Pash was put in charge. Their mission was to follow closely in the footsteps of the Allied invasion armies and capture whatever resources, personnel and information they could find that might have clues as to whether the Germans had a bomb program and whether it had a chance of success. Pash was the military leader; there was also a scientific leader, Samuel Goudsmit, whose job it was to interpret what they uncovered. The mission was called the ALSOS mission, after the Greek work for "grove," which did not please Groves at all, but he was reluctant to change it and, in the process, call attention to the mission.

The ALSOS mission was much trickier than one might think. To prevent the enemy from destroying records and hiding materials, the ALSOS team had to arrive almost simultaneously with the first invading troops. Rome was the first to fall to the Allied invasion, and the ALSOS team entered the theater of operations there, but found no threat from the Italians. They entered France shortly after D-Day, and Pash was charged with finding and taking into custody Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie in Paris, who was the closest thing to a nuclear expert in all of France. Pash and his small team entered Paris literally with the first liberating French troops on Aug. 25, 1944 – they were the very first Americans in Paris – and Pash soon found Joliot-Curie in his laboratory, which was confiscated, with Joliot-Curie being taken into protective custody, and subsequently sent to England.

As the Allies moved into Germany, ALSOS was right there, interrogating captured German scientists, trying to pin down the locations of the German physicists most likely to be developing a bomb, which included Otto Hahn, who discovered fission in 1938; Werner Heisenberg, the most brilliant of all the German atomic physicists; and Max von Laue, the latter two located in Hechingen in the Würtemberg area of Germany. The team determined that Heisenberg had begun building a nuclear reactor in Berlin, which had been moved to Haigerloch, and the ALSOS team found the remains of the reactor, which had never become operational, in April of 1945. They also found Hahn, Heisenberg, and von Laue, and took them all into custody, along with 7 other prominent German physicists. The ALSOS team was only days ahead of the Russians, who also wanted to get their hands on the cream of the German scientists. The Russians were successful in nabbing some of the top German rocket experts. But not the nuclear physicists. ALSOS beat them to it.

Even before they found Heisenberg and his colleagues, Pash and his team were certain that the Germans had not built a bomb, and were not even close to doing so. They kept going because the Americans back home refused to believe that the German bomb effort was a failure, with all that brainpower at hand.

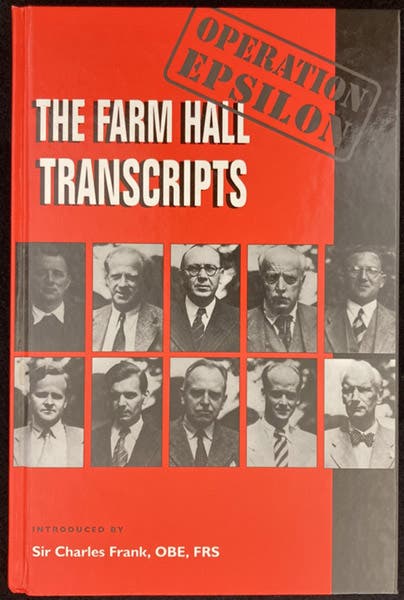

Printed front board, Operation Epsilon: The Farm Hall Transcripts, Univ. of California Press, 1993; Heisenberg and von Laue are in top row, 2nd and 4th from left; Hahn is in the center of the bottom row (author’s copy)

Pash's role ended with the completion of ALSOS in the fall of 1945, but the story had a final act, which we thought we would mention here. The ten German physicists were taken to England in June of 1945 and kept there for about six months, sequestered at an estate called Farm Hall, in a move that was code-named Operation Epsilon. The physicists were not interrogated, but their rooms were bugged and their conversations were recorded, in an effort to understand why the German bomb effort had been unsuccessful. Much later, the tapes were declassified, translated, and printed as the Farm Hall Transcripts (sixth image), and they are interesting to read, especially the conversations after Aug. 6, when the first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, much to the astonishment of all the German scientists. The transcripts are inconclusive as to why the Germans failed to build a bomb, although Heisenberg suggested that this was a deliberate failure, since they did not want Hitler to win the war. Others complained of a lack of resources and manpower and of bureaucratic ineptitude, so those were probably factors as well.

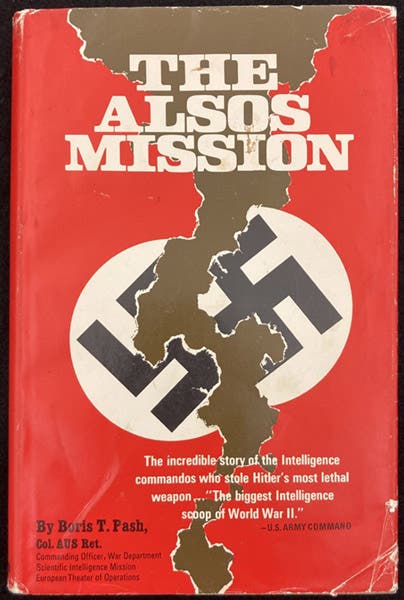

Dust jacket, The ALSOS Mission, by Boris T. Pash (Award House, 1969) (author’s copy)

Pash later wrote a book about his war activities, called The ALSOS Mission (1969), the dust jacket of which we show here. In a way, it was a delayed response to Samuel Goudsmit’s ALSOS (1947), where Goudsmit had taken most of the credit for the success of the mission, and generally mentioned Pash only to criticize his military decisions. It is clear from Pash’s book that the ALSOS mission would have gone nowhere without his leadership.

Pash died on May 11, 1995, at the age of 94.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.