Scientist of the Day - Bertel Thorvaldsen

Bertel Thorvaldsen, a Danish sculptor, celebrated his “Roman birthday” on Mar. 8, having been born around 1770. Thorvaldsen did not know his actual birthdate, but he moved to Rome in 1797, entering the city on Mar. 8, and he considered that the beginning of his artistic life. He remained there for over 40 years. Rome was a perfect place for Thorvaldsen, for he was smitten with the classical form, and for the rest of his life, he would sculpt in the neoclassical style, with nary a nod to Romanticism. He became quite famous in his native land, despite his prolonged absence, and when he finally returned for good, in 1838, he was treated like a hero home from the wars and feted everywhere.

Thorvaldsen receives celebration here because, from 1822 to 1830, he designed and completed the world’s best-known statue of the great Polish astronomer, Nicolaus Copernicus. The statue was commissioned by the Society of Friends of Learning in Warsaw and was put in place in 1830 in front of the Society’s headquarters, now the Polish Academy of Sciences. It is interesting that Thorvaldsen elected to represent Copernicus with a pair of dividers and an earth-centered armillary sphere. Thorvaldsen evidently chose to ignore the pictorial tradition that depicted Copernicus holding a sun-centered “lollipop” that represented his new heliocentric system. But it doesn’t matter, for his image of Copernicus the man is a powerful one. It is not surprising that it has been copied several times, for Expo 67, the World’s Fair in Montreal in 1967, and for the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, where a replica was commissioned to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Copernicus’s birth, in 1973. We show below the statue in Chicago (fifth image).

Much of the preparatory work for the Copernicus statue – sketches, models, and plaster casts – survives and is preserved in the Thorvaldsen Museum in Copenhagen (fourth image, below). We show here the full-size plaster model used to make the bronze casting in Warsaw (third image, above). The museum is crammed with Thorvaldsen sculptures – nearly all of them neoclassical and thus not exactly in vogue at the moment. But it is evident that he was a very talented sculptor.

Thorvaldsen’s other well-known sculpture is one of Johannes Gutenberg that stands in Mainz, Gutenberg’s birthplace. We thought about discussing it further here, but all the captions for the Gutenberg models in the Museum are qualified by the statement: “by H.W. Bissen in accordance with Thorvaldsen’s instructions.” so it is not clear, at least to me, that this is truly a Thorvaldsen sculpture. But you can see it here, if you are curious.

I would like to call your attention to one appealing feature of the Thorvaldsen Museum: it has an exceptional website, where you can find every item in the museum and images of most of them, and all of the relevant correspondence in the archives, as well as references to the many sculptures by Thorvaldsen that are in other places. If you have tried searching for artwork on other museum websites and have been frustrated, give this one a whirl. Here is the home page; click on the Q search icon at top right, type in “Copernicus,” and see what comes up. You could try the same exercise with “Gutenberg,” if you are so inclined.

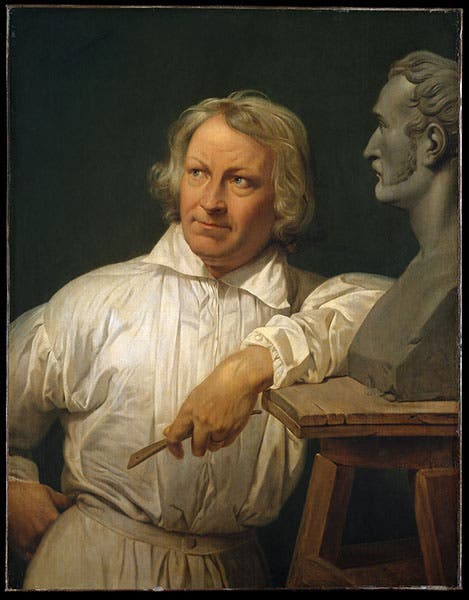

There are many portraits of Thorvaldsen, but I like the one above, painted by Horace Vernet in 1833, when Thorvaldsen was about 63 years old. I like it because the bust that Thorvaldsen has just finished sculpting in the painting portrays the man painting the picture, Vernet. The painting we show is actually a copy by Vernet in the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the original, appropriately, is in the Thorvaldsen Museum.

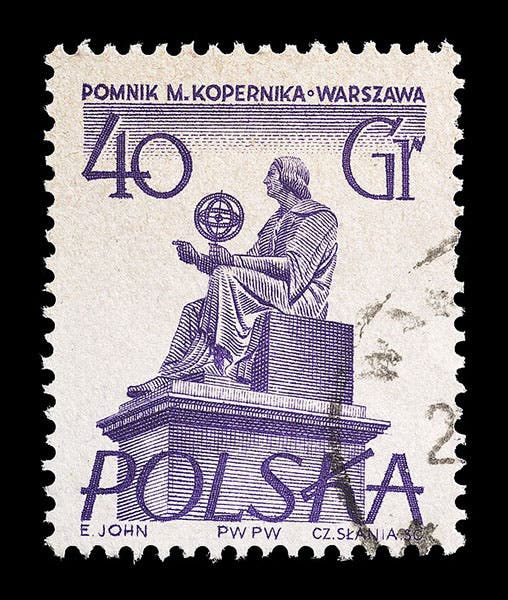

Poland issued a postage stamp in 1950 honoring, not Copernicus, but the statue of Copernicus by Thorvaldsen. The statue had been the site of an extended graffiti campaign during the German occupation in the Second World War; it was then seized by the Germans, who planned to melt it down for the copper. Fortunately, the war ended before they could do so. The statue had been much damaged, but it was restored and returned to its proper location in front of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw in the summer of 1949. The stamp says, in essence, welcome back!

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.