Scientist of the Day - Benjamin Silliman

Linda Hall Library

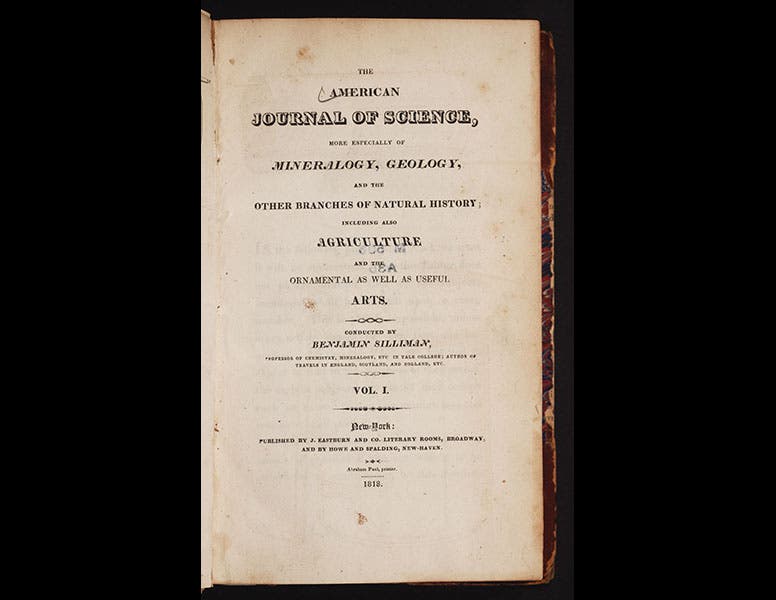

Benjamin Silliman, an American chemist and geologist, was born Aug. 8, 1779. Silliman graduated from Yale and was appointed professor of geology and natural history in 1802, before he had any training whatsoever in those two fields. To his credit, Silliman studied in Philadelphia for two years, and then travelled to England and Scotland to study for several more years, and to buy equipment for his new professorship. When he did return, he rapidly established himself as a prominent scientific figure. He did not make any major discoveries, but he did found and edit a journal, the American Journal of Science and Arts, which had its first issue in 1818 (third image) and is still being published, making it the oldest continuously published scientific journal in the United States. For the first half of its life it was usually referred to as Silliman’s Journal. Silliman also began Yale’s famous mineral and meteorite collection by acquiring other collections and sometimes by finding his own, such as the famous Weston meteorite that he acquired in 1807, and which is still in the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale (founded in 1876).

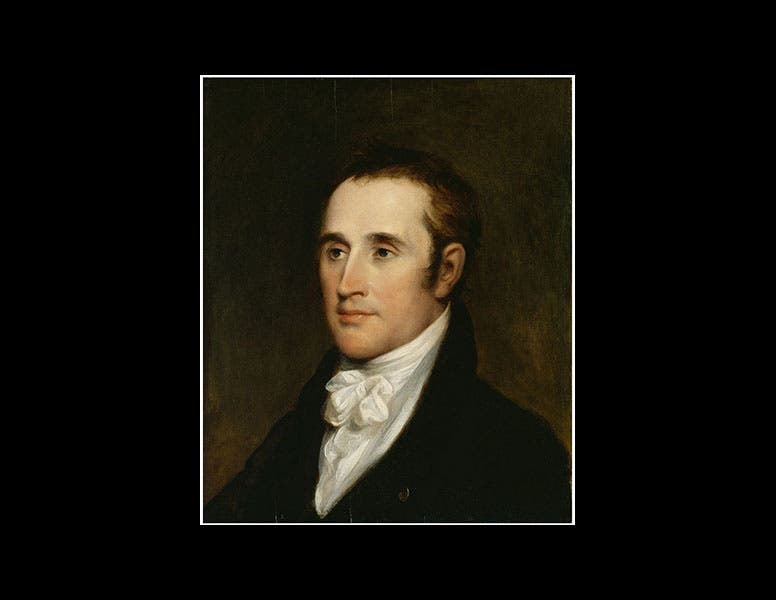

One of Silliman's most notable achievements had nothing to do with sciences, but was a milestone in the field of gift planning. In 1830, he visited the Connecticut artist John Trumbull, then living in New York City. Trumbull had been the major visual recorder of the American Revolutionary War. Four of his large paintings, including the Signing of the Declaration of Independence and the Surrender at Yorktown, were commissioned by the government and hung in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol in Washington in 1825. But when Silliman visited in 1830, Trumbull was 75 years old and had no appreciable income. His apartment was filled with his paintings from the days of the Revolutionary War, including the original small versions of the Signing of the Declaration (first image) and the Battle of Bunker's Hil (fifth image), along with portraits of George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, and dozens of miniatures. Trumbull indicated that he would be happy to give his collection to Yale, if they would just give him an annual allowance that he could live on until he died.

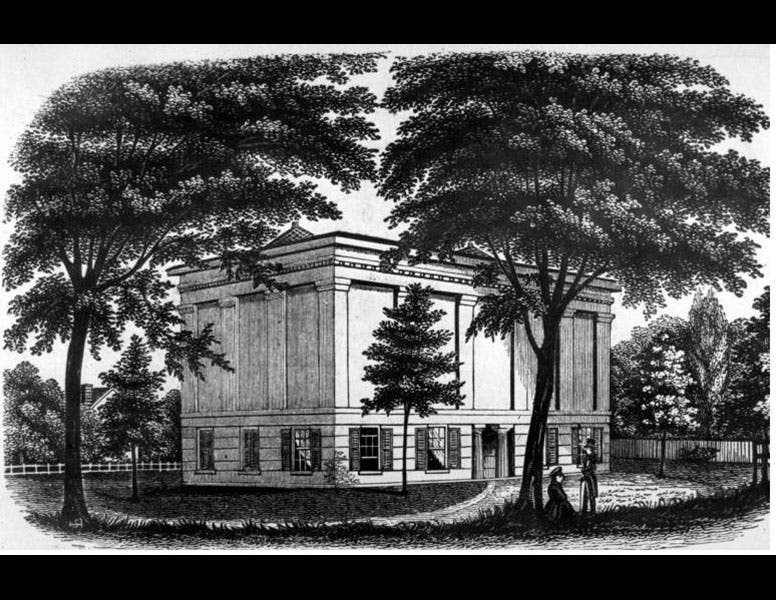

Silliman went back to Yale and immediately corralled the president, and they started to work on an agreement that would be mutually agreeable to all. Silliman, who had trained in law before converting to science, himself worked out most of the details, including finding donors to fund the annuity. Yale agreed to pay Trumbull $1000 a year for life and promised to build a gallery for the paintings, a building that they allowed Trumbull to design. This was the first charitable gift annuity in the United States, and the Trumbull Gallery was the first college art museum in the country. By the time Trumbull died in 1843, the building had been completed (fourth image), and it was soon filled with Trumbull’s paintings, more than 100 works of art, the largest Trumbull collection in the world. And as per the agreement, they are all still there (although the originally building was razed in 1905 and later replaced with the Yale University Art Gallery).

So if you want to see the Surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, head for New Haven, Connecticut (sixth image). But if you want to see Trumbull’s portrait of the young Benjamin Silliman, you need to visit the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C (second image). That one escaped.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.