Scientist of the Day - Benjamin Franklin

In the second quarter of the 18th century, an Irish musician decided to use the musical properties of glass goblets to produce a new musical instrument. As you know, if you rub a moistened finger around the rim of a crystal wine glass, a clear tone is produced. If you add water (or wine) to the goblet, you can change the pitch of the tone. So if one has a couple dozen wine glasses, of different sizes with different amounts of fluid in them, one ought to be able to produce a multiple set of tones, and by proper tuning (adding or subtracting liquid), it ought to be possible to generate several octaves of a musical scale. The problem with musical glasses is that they are hard to tune and, with two hands, it is difficult to play more than two notes at once. Nevertheless, the ethereal quality of the tone produced made water glasses a popular parlor instrument in England and France in the middle of the 18th century, and there are stlll street musicians who are remarkably adept at coaxing beautiful tones form water-filled glasses, as in this video.

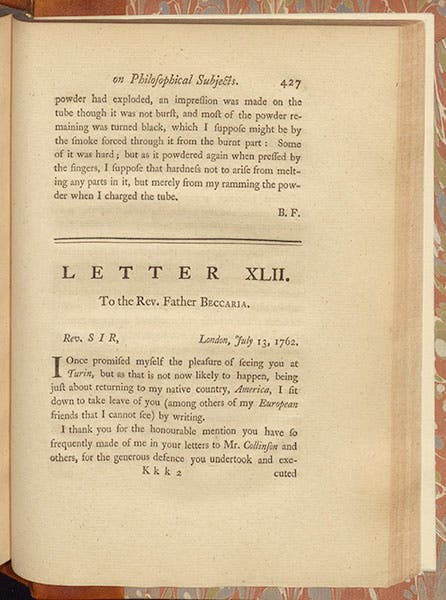

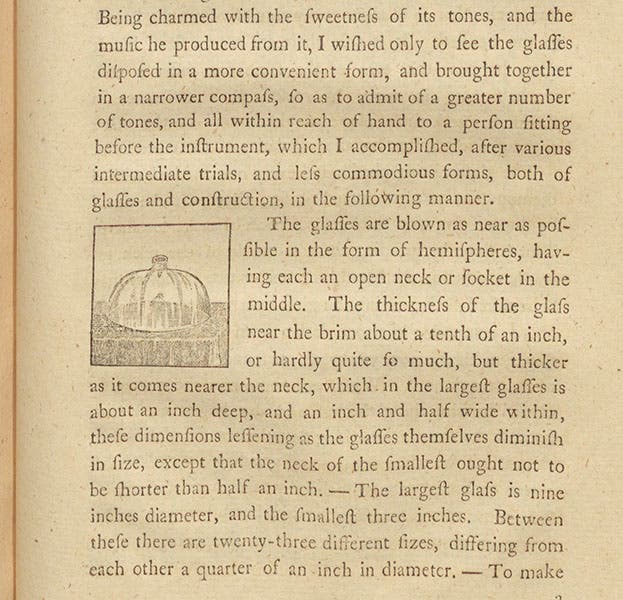

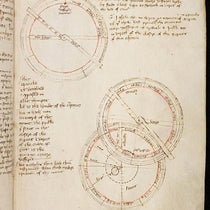

In 1757, Benjamin Franklin moved to London from Philadelphia, and he would be there, except for periodic brief returns to the Colonies, until the eve of the Revolutionary War. We have already written one post on Franklin and his work in electricity. Franklin saw and heard his first set of musical glasses at the Royal Society of London in 1759. His mental gears must have started whirring at once, because by 1761 he had commissioned a new instrument of his own design from an instrument maker, and on July 13, 1762 he wrote a letter to a colleague in Italy, Giambattista Beccaria, describing his invention. Since it is the only document by Franklin that discusses his brainstorm, it is quite famous, and deservedly so. It was only printed once, in the 4th edition of Franklin’s Experiments and Observations on Electricity (1769), and we show you several pages from our edition (second and third images)

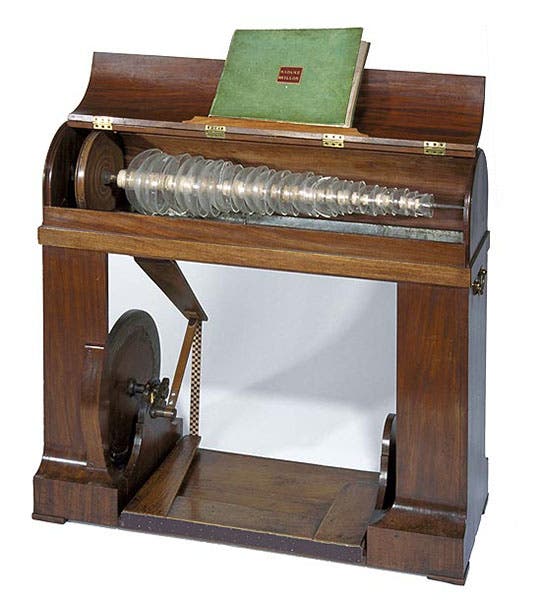

I like the letter because, in pointing out how musical glasses could be transformed into a much-improved instrument, Franklin demonstrates quite clearly the difference between inventive genius and the rest of us. Here is what Franklin suggested (I have reworded and shortened, but have retained, I hope, Franklin's intent and meaning): 1) get rid of the water tuning; 2) remove the stems from the glasses, turning them into bowls; 3) make them of different sizes, so they will nest; 4) mount them all on a common shaft, so that they can all be turned at once; 5) place the shaft of bowls on its side, like a lathe, all 25 of them (37 in later models), tapering and nesting; 6) color-code the rims so you can identify the different pitches; 7) have some water available in a bowl to keep fingers and bowls moistened; 8) place a heavy flywheel on the end of the shaft so that it turns evenly; 9) attach the shaft to a foot treadle so that it can be easily rotated; 10) moisten your fingers, place them on the rotating bowls, pump the treadle, and play away, 10 notes at a time, if you have the usual number of fingers. He called his instrument an Armonica. We show here an original Armonica, unrestored, at the Franklin Institute (fourth image); another original, restored, at the Bakken Museum (first image), and several replicas, including one at the Benjamin Franklin Museum in Philadelphia (fifth image), and another at the Benjamin Franklin House in London (sixth image).

Replica of a Franklin Armonica, Benjamin Franklin Museum, Philadelphia (photo by the author)

It was not quite this simple, of course. Franklin advised that you make half-a-dozen bowls of each size, to ensure that you have one that will produce the proper note, or close to it. Then each bowl must be ground down, made thinner, to get the pitch exact. And it is not easy to mount them on the tapered iron shaft – Franklin used a cork bushing for each bowl, but it had to be precisely sized; too loose and the bowl would not turn, too tight and the bowl or bushing would crack. But still, this is such an amazing feat of ingenuity – to start with a device that is a clumsy novelty at best, change every single facet of its design and construction, and end up with an instrument for which it was worth writing music, is quite remarkable. Franklin was apparently personally involved in the construction of his first instrument, which he played as well. The Armonica became immensely popular, and many composers wrote music for it, including Mozart. Here is a brief video of one being played.

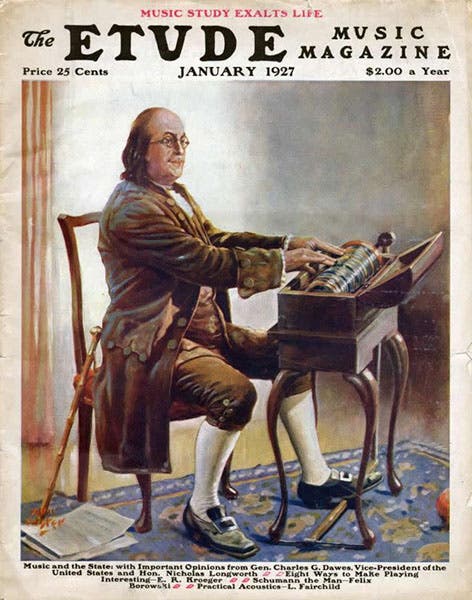

Our last image is not especially historical; it is even a bit campy, in a Norman Rockwellian kind of way. It is a recreation of Franklin playing his Armonica, painted by Alan Foster, and it appeared on the cover of The Etude Music Magazine in 1927. For some reason, it quite appeals to me, and I have ordered my own copy. When it arrives, I will photograph the cover and replace the image I now show, drawn from an online source. Unless I hear protests, that is, in which case I will just place it on an easel in my office and enjoy it all by myself.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.