Scientist of the Day - Basil Besler

Basil Besler, a German apothecary, botanist, and collector, was born Feb. 13, 1561, in Nuremberg. He is best known as the author of the Hortus Eystettensis (1613), a magnificent illustrated folio account of the gardens of the prince bishop of Eichstatt, which Besler had a hand in establishing and planting. This is a splendid book, often hand-colored, but as we do not have it in our collections, we will immediately move on to a rather different Besler publication that we do have, and which I find even more interesting than his garden book. The book is called Continuatio rariorum et aspectu dignorum varii generis quę collegit et suis impensis ęri ad vivum incidi curavit atque evulgavit (1622), which roughly translates as A Continuation of various kinds of rare and worthy objects, collected and engraved from life at his own expense and now made public by Basil Besler.

This is what we call, for short, a “museum book” – a work describing a Collection of Curiosities or Kunstkammer. There were many such collections and many such books describing them in the 17th century; we have already in these posts discussed the slightly later museum book of Ole Worm, and we have at least a dozen more published in the 17th century. In the preceding century, there had been many collectors, but no books describing them, so the museum book is a 17th-century phenomenon, continuing on into the first half of the 18th century.

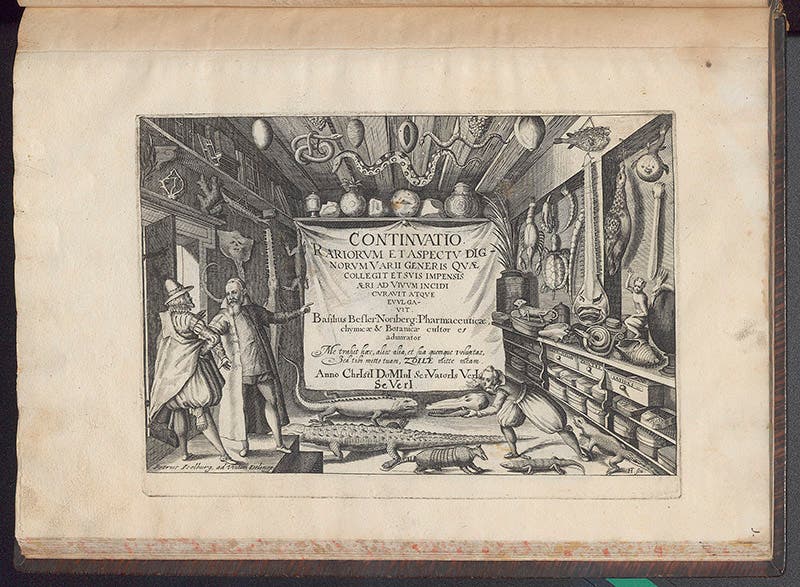

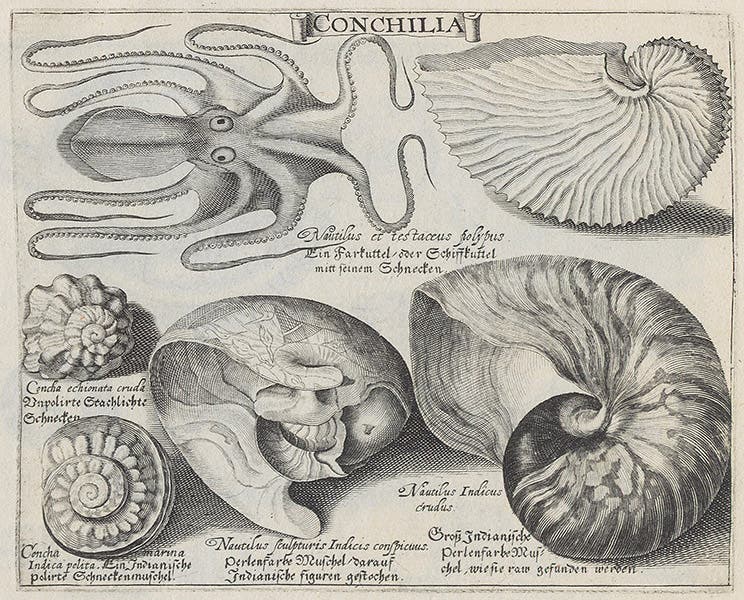

Typically, a Kunstkammer or Wunderkammer was put together by a prince or a prominent citizen for the purpose of display to invited visitors, in order to increase one’s standing. The objects displayed were usually exotic – the more exotic, the better – and sometimes the naturalia were transformed into mirabilia by artisans, as for example by adding golden feet and feelers to a nautilus shell to turn it into a snail. The published descriptions usually began with a frontispiece that showed the collection as if housed in one room – a wonder room – which might or might not reflect the actual appearance of the collection, or even the true objects in the collection. Worm’s frontispiece is probably the most famous of these depictions. The rest of the typical museum book usually had few illustrations, just descriptions.

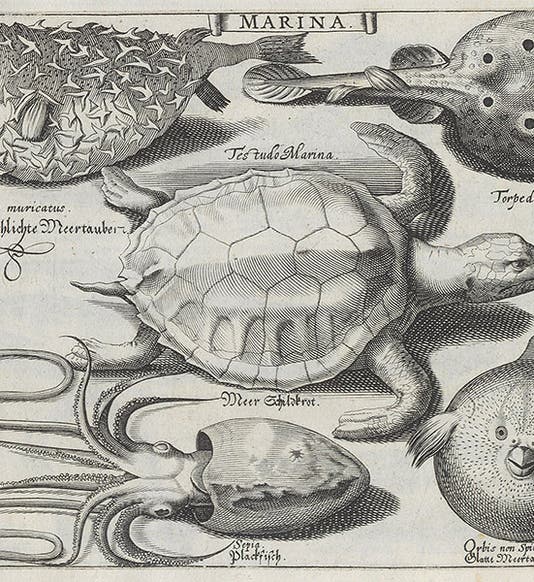

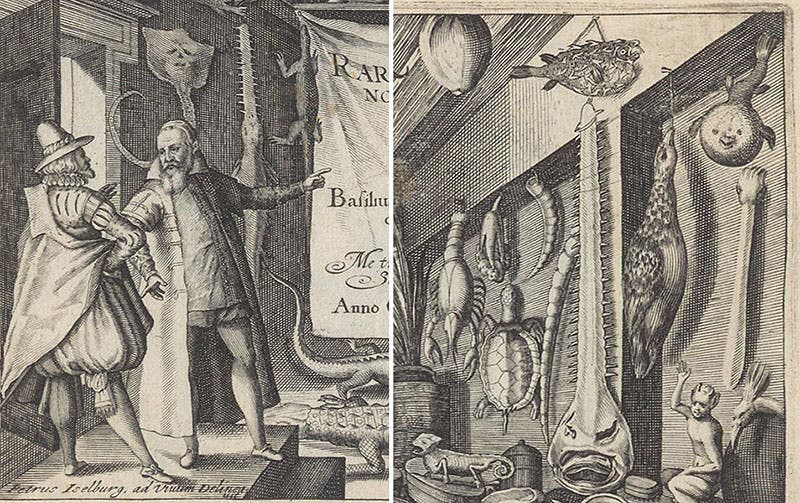

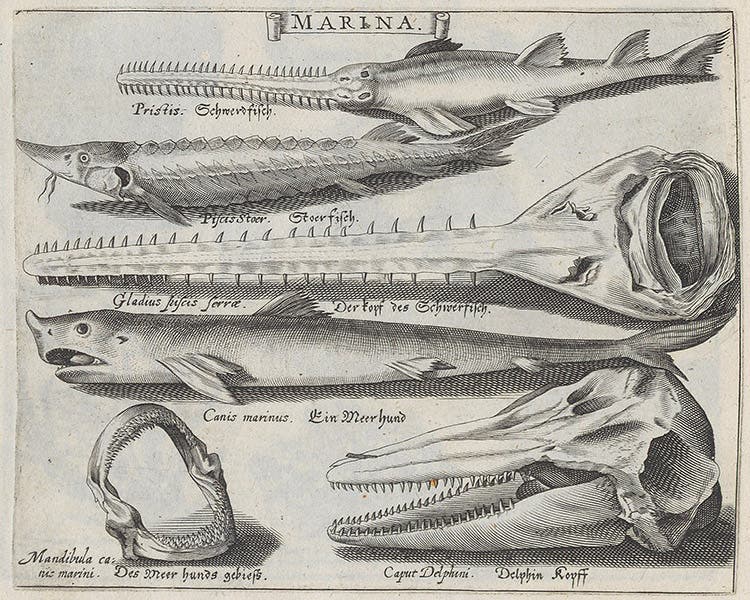

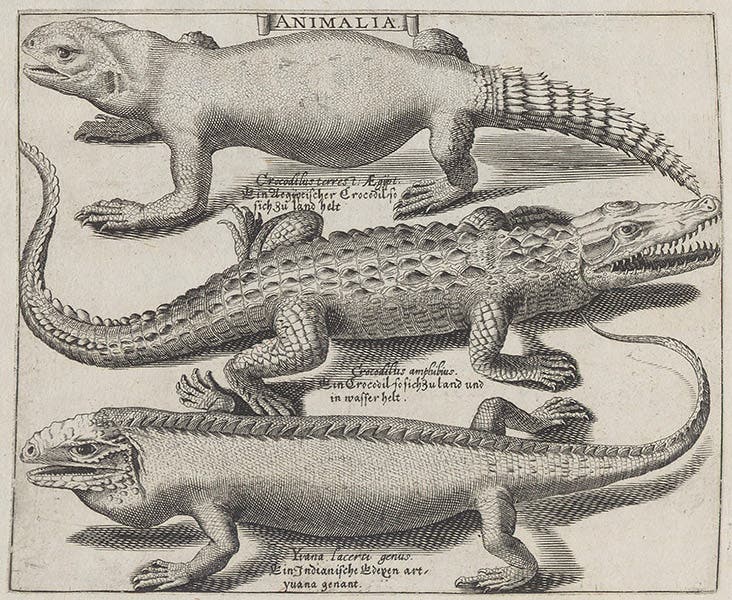

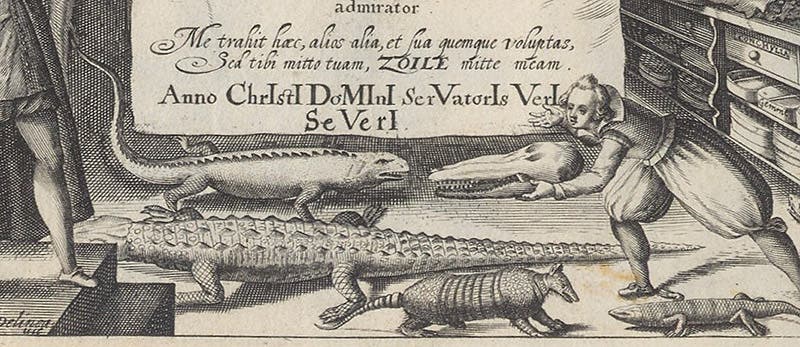

Besler began his book with just such an engraving, where we can see many of the objects in his collection (second image). Besler himself is at the left, welcoming a visitor, which was the whole point of collecting at the time. Among the objects displayed we can see crocodiles and iguanas, sawfish and puffer fish, turtles and armadillos, as we show in three details (third, fourth, and last images).

What makes Besler’s book different is that it contains many engraved plates within (in fact, the book has no printed text at all), and the objects shown on these plates are the same as those shown on the frontispiece. That does not mean these are actually what his objects looked like, but at least there is an attempt at consistency that is missing in nearly every other museum book. We show four of these plates, and you can, if you wish, match up the objects in the plates with those in the titlepage engraving.

I saved the detail of the bottom of the engraved titlepage for last, because it shows an interesting feature of the title panel. The date is provided in the form of a chronogram, where the phrase that begins “Anno Christi Domini …” has a number of capitalized letters, which, when extracted, read “CIIDMIIVIVIVI”. Rearrange these and you find the date of publication: MDCVVVIIIIIII, or 1622.

Besler died in 1629. He did not live, fortunately, to see the Eichstatt gardens destroyed by invading Swedish troops in 1633. What became of his collection, we know not.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.