Scientist of the Day - Bartolomeo Eustachi

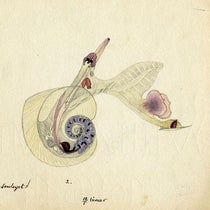

Bartolomeo Eustachi, a Roman anatomist, died Aug. 27, 1574, probably around the age of 65. In 1543, he witnessed the publication of one of the great books on anatomy (indeed, one of the milestone books of the entire history of science), when On the Fabric of the Human Body, by Andreas Vesalius, first appeared in print. With its large woodcuts, artfully drawn from observations made by Vesalius himself, it instantly revolutionized anatomical illustration and the teaching of anatomy, and almost every anatomical text compiled between 1543 and 1650 looks just like Vesalius’s book – except for that of Eustachi. He started preparing illustrations for an anatomical text in the 1550s, and they could not have been more different from those of Vesalius. The Vesalius illustrations were woodcuts, very classical in appearance, the bodies standing like ancient sculptures in charming landscapes. Eustachi used copper-plate engravings, and his figures were not classical but mannerist – each body, rendered as muscle man, vascular man, or skeletal man. enclosed in a graduated grid, pushing against the confines of its restraint in varied and wonderful ways, If Eustachi’s Tabulae anatomicae had appeared as scheduled, there might have ensued a wonderful confrontation between partisans of the classical Vesalian style and advocates of the mannered Eustachian style. But even though the illustrations were drawn and engraved, Eustachi’s book was not printed, for reasons unknown. The manuscript did not come to light until 1714, when the copperplates were discovered in the Vatican Library and finally sent to the press. Even 150 years too late, the plates had a profound impact on 18th-century anatomy, and the book went through several editions.

Four years ago, we published a post on Giovanni Maria Lancisi, the 18th-century physician who recovered the Eustachi manuscript and plates and had the work published. I included with that post my five favorite Eustachi engravings – I encourage you to take a look at them. We are still under pandemic restrictions and can only show two images today, so I chose two different ones, and provide links to three others that I have not shown before. The two plates here show a muscle man viewed from the front and from the rear, in typical Eustachian poses. The links take you to: a vascular man from the back; a different muscle man from the front; and a skeletal man looking up. This total of ten plates, plus the title-page vignette shown in the Lancisi post, pretty much capture the spirit of Eustachi’s still-born attempt at his own anatomical revolution.

I know of no documented formal portrait of Eustachi. But if we assume that the title-page vignette shows Eustachi at work, then we can zoom in to show you an informal portrait of the great anatomist (third image). Our edition of Eustachi is the 2nd edition, 1728; to the best of my knowledge, the plates are the same in both the 1714 and 1728 editions. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.