Scientist of the Day - Barthelemy de Lesseps

Jean Baptiste Barthélemy de Lesseps, a French diplomat and adventurer, was born Jan. 27, 1766. Barthélemy grew up in St. Petersburg, where his father was the French consul, and he learned to speak Russian, German, and French when still quite young. He must have showed great promise, for he was sent to Paris by the French Ambassador on a diplomatic mission in 1785, when he was 19 years old. Once in Paris, he came to the attention of Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Perouse, who was busily planning a circumnavigation of the world, with an extensive stop-over on the Kamchatka peninsula of Russia. It occurred to the senior officers that they would need a translator while in Russian territory, and de Lesseps, despite his youth, seemed the perfect choice. So de Lesseps was appointed by the French minister to succeed his father as consul in St. Petersburg, and he was dispatched to his post via the La Perouse expedition, with the expectation that once his translating duties were done, he would disembark and head across Russia to take up his duties in St. Petersburg.

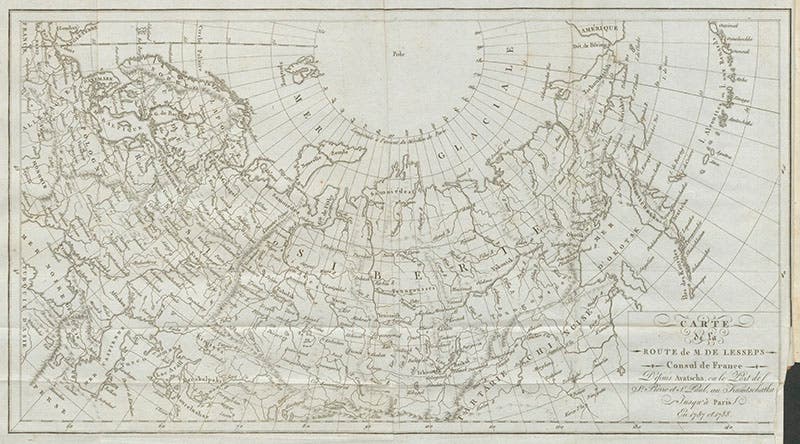

On Aug. 1, 1785, de Lesseps set sail on the Astrolabe and Boussole with La Perouse, and they duly arrived at Petropavlovsk on the eastern coast of Kamchatka on Sep. 6, 1787. De Lesseps fulfilled his translating duties, and when the ships were preparing to set sail to Australia, and thence home, de Lesseps was released from duty and allowed to head back overland to St. Petersburg. At the last minute, La Perouse decided to entrust his precious logs and journals for the first 2 years of the voyage to the young man, for delivery to the French Ambassador in St. Petersburg, just in case something happened to him or the ships.

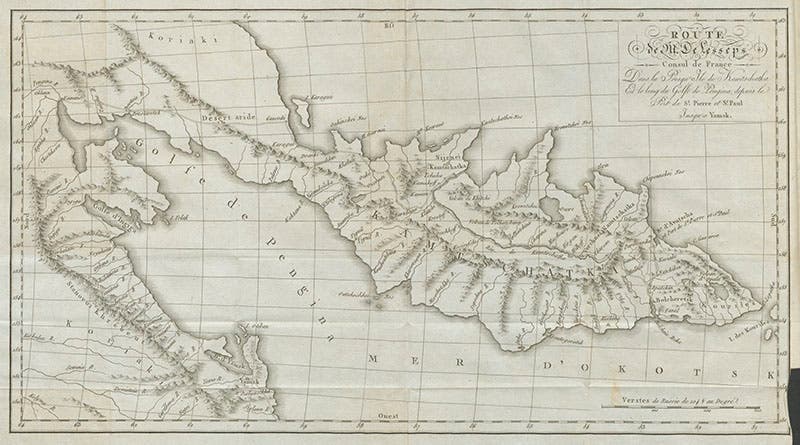

De Lesseps set out by dogsled from Petropavlovsk on Oct. 17, journals and logs carefully packed away. The first leg was to go all the way up the peninsula, and then down the other side of the Sea of Okhotsk to Okhotsk (see map, third image). It was soon the dead of winter, and this first leg took de Lesseps almost nine months. He surely must have wondered if he would ever get home at this rate. But things slowly got better, and once he got to Yakutsk, he was able to turn in his sleighs and carts for a boat to navigate up the River Lena. By late summer, he had reached Irkutsk, and soon he was able to take coaches to Tobolsk and Kazan. He eventually reached St. Petersburg on Sep. 22, 1788, where he presented the La Perouse journals to the Ambassador. They were considered so important that de Lesseps himself was immediately dispatched with the journals to Paris, which he reached a month later, on Oct. 17, 1788, and where he was received by the King. He had been on the road for exactly one year, with 9 months having been spent in a desolate and frigid countryside where hardly another soul was to be found. It was one of the longest overland winter journeys up to that time. When it was done, de Lesseps was 22 years old.

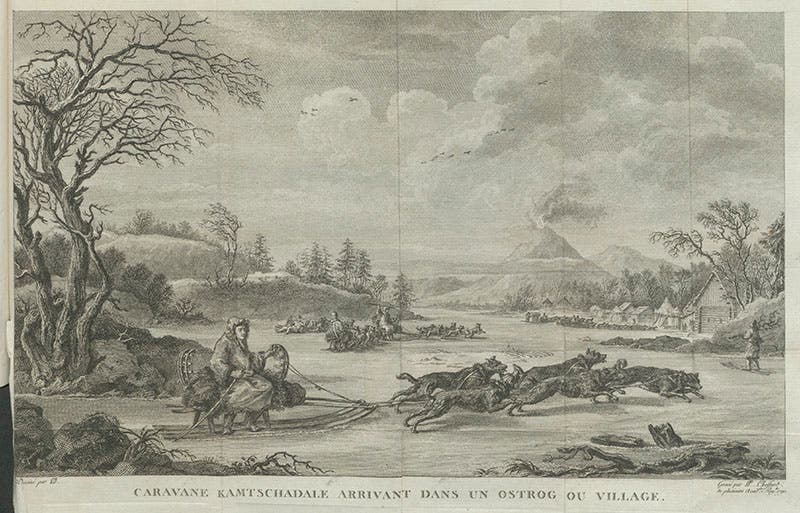

La Perouse's prescience in arranging for the safe keeping of his journals is almost eerie in hindsight. The Astrolabe and Boussole made it to Australia; they departed from Botany Bay on Mar. 8, 1788, and the ships and crew were never seen again. In spite of many searches, the fate of the expedition was not determined until 1827, when artifacts were recovered from Vanikoro Island, in the eastern Solomon Islands (for more on the discovery of the fate of La Perouse, see our entry on Peter Dillon). De Lesseps was thus the only survivor of the La Perouse expedition, unless you count the journals of La Perouse. De Lesseps wrote his own account of his overland crossing, called Journal historique du voyage de M. de Lesseps, consul de France employé dans l'expédition de M. le comte de La Pérouse (1790). We have this work in our History of Science collection, and we have displayed it twice, once in our Voyages exhibition in 2002, and then again in our Vulcan's Forge exhibition of 2004, where it was included because the Kamchatka peninsula is littered with active volcanoes. For both exhibitions, we displayed a plate that shows de Lesseps in a dog sled, with the active volcano Tolbachik in the background, and we show it again here (fifth image), because quite frankly, it is one of the most appealing engravings in the entire annals of scientific exploration. We even show you a detail for our first image.

The journals of La Perouse that de Lesseps had preserved were published in 1797 as Voyage de La Pérouse autour du Monde. We have this in our collection as well.

In case the name “de Lesseps” is vaguely familiar to you, Barthélemy de Lesseps was the uncle of Ferdinand de Lesseps, the entrepreneur who successfully built the Suez Canal in 1859-69, and then failed to construct a French canal across the Isthmus of Panama in the 1880s. We featured him as Scientist of the Day just two months ago. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.