Scientist of the Day - Balto

On Feb 2, 1925, a dogsled raced into Nome, Alaska, carrying serum badly needed to quell an outbreak of diphtheria that threatened the local population. The sled team, led by a Siberian husky named Balto, was the last of a relay of 20 teams that had set out from Nenana, Alaska, six days earlier, and had travelled some 675 miles with their valuable cargo. The modern Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race commemorates the Serum Run of 1925.

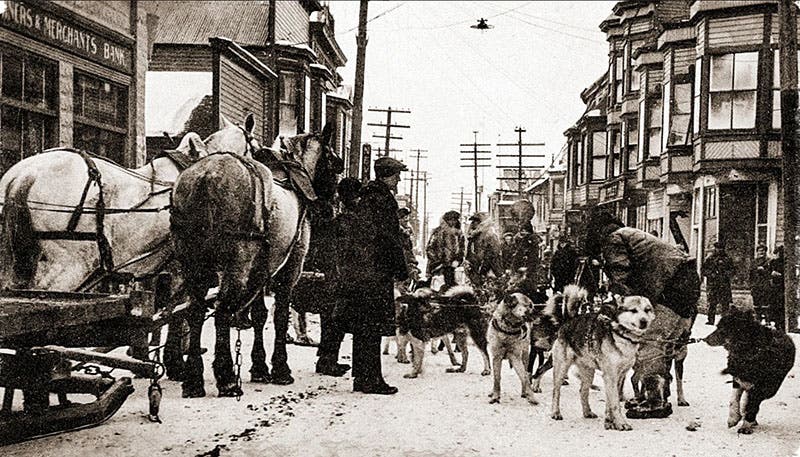

The relief effort was mounted when authorities in Anchorage, 1000 miles to the southeast, received a radio SOS from health officials in Nome on Jan. 20, 1925, informing them that diphtheria had broken out in Nome and asking if any serum were available. Anchorage said yes and was prepared to fly it in, but unfortunately airplane engines in those days could not start at -30°, nor could pilots, in their open cockpits, survive such flights. So they sent the serum by rail to Nenana, some 300 miles north, which was as far as the railroad went, and then sent out a call for dog teams to carry the serum in relays the rest of the way to Nome (see map, second image). Twenty teams responded, led by a mix of Scandinavian, Native American, and Inuit drivers, and the first team set out on Jan. 27. That initial leg was 52 miles, but most of the next 16 teams went 30 miles or less, as the temperature was dropping into the -50s. They averaged 6-9 miles/hour, which is amazing under the conditions, which included total darkness, day and night.

The antepenultimate (18th) team was led by a Norwegian named Leonhard Seppala and his lead dog Togo, and since the team before them had encountered problems, Seppala and Togo ended up racing some 91 miles in all (and this was after they had just travelled 150 miles from Nome to join the relay). They were relieved by a team that ran a 25-mile leg, and then the team of musher Gunnar Kaasen and his lead dog Balto took over, and they carried the serum the last 53 miles and into Nome, saving the lives of numerous Inuit children, who were particularly vulnerable to diphtheria. It was, in the choice words of a Sports Illustrated writer in 2021, "a feat of interspecies heroism that would captivate the country."

Not surprisingly, Kaasen and Balto got a great deal of attention, first from the citizens of Nome, and then from the national press (third image, above). A silent movie was made about Balto (no prints survive), and a statue of Balto was erected in Central Park in New York City, in homage to sled dogs everywhere (first image). Mushers like Seppala were more than a little miffed that they and the other dogs were completely ignored, and Seppala had a legitimate beef, since his leg of the trip was twice as long as Balto's. He must have made some noise about the injustice, for a year later, Seppala and Togo were brought to New York City by the great Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen to receive a medal. Togo, however, did not get a statue. Sports Illustrated last year ran an online story about Seppala and Togo. Note the last part of the story’s URL: /alaska-serum-run-1925-togo-not-balto.

Public attention soon turned elsewhere, and Balto (and Togo) were forgotten. Kaasen was forced to sell his team, including Balto, to a Los Angeles sideshow, where the dogs were discovered in 1927 by a Cleveland businessman who had heard of Balto's exploits and was shocked by the condition in which he found the dogs. With the help of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, he started a campaign to save the dogs, which would require $2000. The funds were raised, mostly by schoolchildren selling cookies and such, and on Mar. 6, 1927, Balto and his 6 sled-mates were welcomed to Cleveland by a parade, and then taken to their new homes in the city zoo, where they entertained visitors daily and lived out their remaining years. After he died in 1933, Balto was taxidermied and mounted and relocated to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where he may be seen today (fifth image).

An animated/live action film, Balto, was released in 1995, with Kevin Bacon voicing Balto, who had morphed into a wolfdog, and a speaking one at that. It received mixed reviews and apparently is a little loose with its historical accuracy. I haven’t seen it – indeed, I didn’t know about it until researching this post – but I intend to check it out, on behalf of my grandsons. I do not know if Togo makes an appearance.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.