Scientist of the Day - Apollonius of Perga

Apollonius of Perga, a Greek mathematician, was born sometime after 245 BCE and died 50 or 60 years later. He is considered one of the 3 greatest mathematicians of Hellenistic Greece, a term we apply to Greek culture after the death of Alexander the Great, which occurred in 323 BCE. The other two were Euclid of Alexandria, who flourished around 300 BCE, and Archimedes of Syracuse, who died in 212 BCE during the Roman siege of Syracuse. Apollonius was the youngest of the three. Euclid died well before Apollonius was born. But the lives of Archimedes and Apollonius overlapped, and the two could have exchanged mathematical insights, had they encountered each other. But there is no indication they ever did.

We do not know what Apollonius had to do with Perga, a Greek city on the southern shore of central Anatolia (modern Turkey). He must have been born there, but he spent all of the life we know about in Alexandria, the new city on the Nile delta where the Ptolemaic dynasty established the famous Library and Museum. There Apollonius studied and wrote a number of works on a variety of subjects, of which only one substantial treatise has survived. But it is a beauty. It is called Conics.

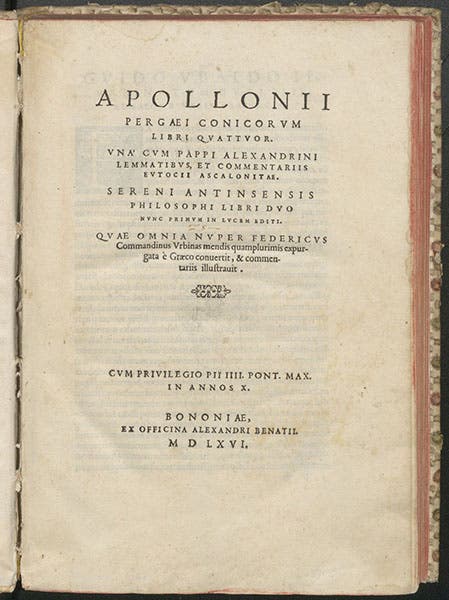

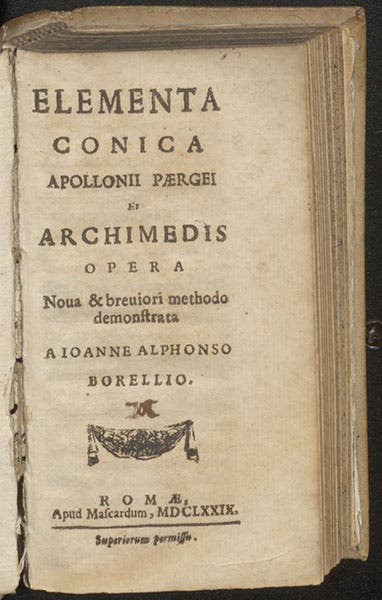

Apollonius discovered and proved (using the Euclidean method) just about everything one person could discover about conic sections – those two-dimensional curves that you get by slicing a cone with a plane at different angles. He found there are four kinds of these, and he gave three of them the names we still use – ellipse, parabola, hyperbola – to go with the fourth, the circle. Whatever you might know about conic sections – that, for example, an ellipse is the locus of all points, the sum of whose distances from two foci is a constant – Apollonius already knew. So the history of conic sections in Renaissance and early modern times is essentially a history of commentaries on Apollonius. We have many of these in our library, written by the best mathematicians of the era, including Federico Commandino, Giovanni Alfonso Borelli, Isaac Barrow, and Edmond Halley, and we show the title pages of several of these here. Johannes Kepler did not write a commentary, but he did something even better – he applied the Conics to the solar system and showed that the planets move in elliptical orbits with all the properties that Apollonius had demonstrated for such curves.

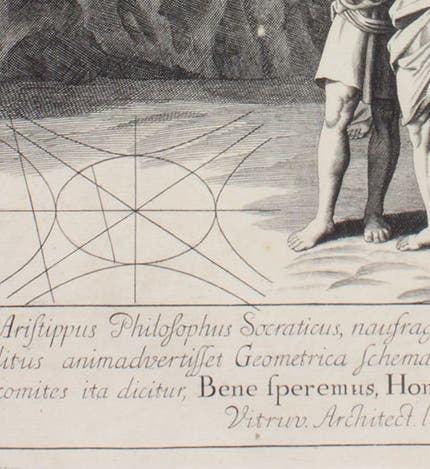

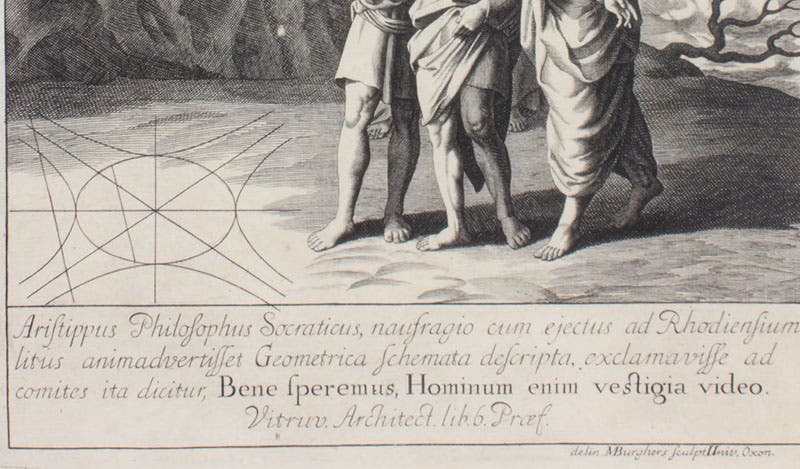

One of the least showy Conics editions in our Library is the 1679 octavo edition by Borelli, which shrinks all the diagrams onto a few crowded plates at the back (third and fourth images). The most impressive is a small folio edited by Edmond Halley in 1710, with a frontispiece engraved by Michael Burghers (fifth and sixth images). It illustrates a passage from Vitruvius, who related a story about Aristippus, shipwrecked with his shipmates on the island of Rhodes. When he glimpsed some geometric figures in the sand, he said to his friends: "Bene speremus, hominum enim vestigia video" – "Raise your hopes, for I see the vestiges of mankind." If we look closely (the first image is a detail of the lower left corner of the frontispiece) we see some conic sections, which could only have been drawn by some very civilized people.

This Apollonius frontispiece would be more impressive if it were truly original. In fact, Burghers had initially engraved it for a 1703 edition of Euclid, edited by David Gregory, where the geometric figures in the sand were Euclidean triangles. For the Apollonius edition in 1710, all he had to do was substitute hyperbolas for triangles. Eighty-two years later, when all these actors were dead and gone, another editor revived the still extant copper plate for an edition of the works of Archimedes, and replaced the figures in the sand once more, this time using diagrams from Archimedes’ treatise on the spiral. We illustrated all three frontispieces in a post on Gregory some years back.

There is no portrait of Apollonius. Greece needs to think about inventing one for another postage stamp, as they did for Democritus.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.