Scientist of the Day - Andrew Ure

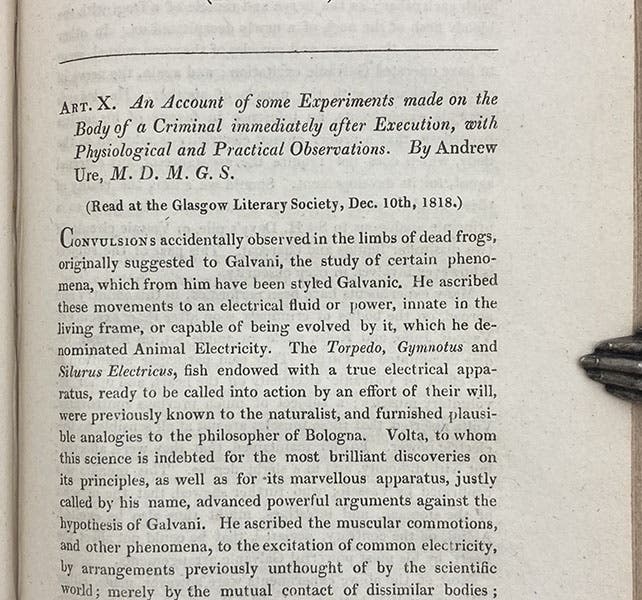

On Nov. 4, 1818, Andrew Ure, a Scottish physician teaching in Glasgow, performed an unusual post-mortem experiment. The object of study was the body of a criminal, Matthew Clydesdale, freshly delivered from the gallows. Clydesdale had been convicted of murdering a man with a pickaxe, and he was hanged in Glasgow shortly after his sentence. Hanged criminals were highly prized, since they were the only cadavers that could legally be dissected at anatomical institutions, and their remains were fought over by anatomy instructors at medical schools. James Jeffray, professor of anatomy at the University of Glasgow, claimed this one, and he invited Ure to assist him in a public dissection, probably because Ure had an interesting idea: to subject the body to electrical jolts from voltaic piles to see if the spark of life could be reawakened, if only briefly. The relationship between electricity and life was a hot topic in the early 19th century, and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein had been published (anonymously) just 8 months before Matthew Clydesdale was executed. Could another Frankenstein's monster be brought back to life in Glasgow?

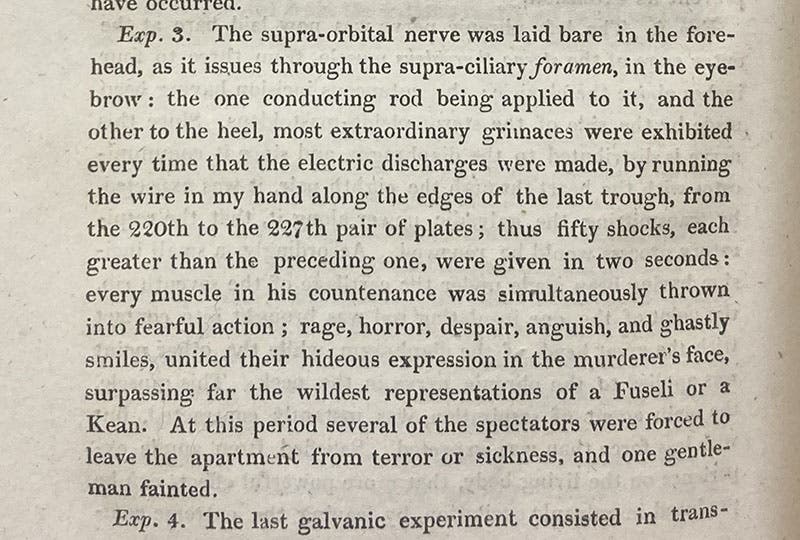

Although Ure was the junior man at the dissection, he gets most of the attention and credit, because he read an account of the galvanic experiments to the Glasgow Literary Society in early December, and then published his remarks in the Journal of Science and the Arts in 1819, a series that we have in the Library. We show here the first paragraph of his published paper (third image), and a paragraph from the body of the remarks, where he describes his most sensational experiment, exciting the corpse’s facial muscles (fourth image).

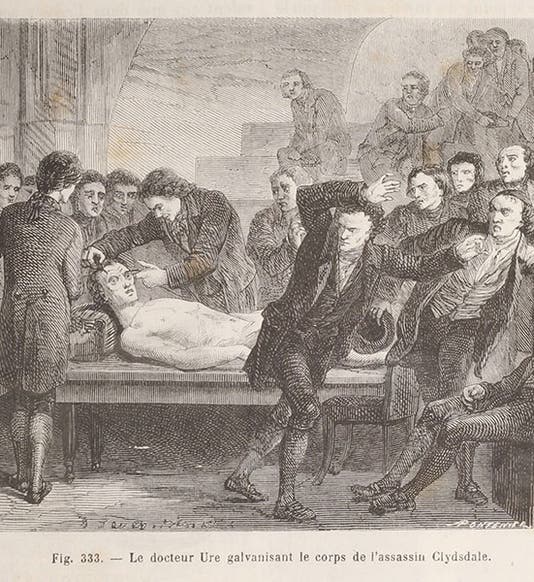

Ure first subjected the body of the cadaver to a variety of galvanic shocks, touching an electrode to Clydesdale's leg and chest, producing convulsive reactions in each case. For his third experiment, he laid bare a nerve above the eyes, and when he touched it with his probe, it produced reactions of anger, horror, rage, even "ghastly smiles," from the dead man's countenance. Ure even had the clever idea of dragging the wire across the exposed plates of the Voltaic pile, and each time it touched a plate, a new pulse of electricity shot through Clydesdale, so that the cadaver received 50 shocks in two seconds. This caused a cascade of grimaces, "surpassing by far the wildest representations of a Fuseli or a Kean," and causing some of the onlookers to flee in terror. You can read much of this in our extract from page 290 of his journal article (fourth image).

The only image of the Clydesdale experiments known to me appeared 50 years later, in Louis Figuier's Merveilles de la science (1867), a work that we have relied on many times in this series for visual renditions of historical events. It is not surprising that the moment Figuier chose to recreate was experiment 3 on the facial muscles (first image).

One of the best introductions to Mary Shelley’ Frankenstein and its connection to medical electricity of the time is an exhibition catalog, curated by a one-time classmate of mine, Susan Lederer. It was mounted at the National Library of Medicine in 1997, and was called: Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature (Rutgers University Press, 2002). The exhibition did an excellent job of demonstrating the scientific milieu out of which Frankenstein sprang, and even included our Dr. Ure and his experiments on Mr. Clydesdale. It is probably a difficult catalog to obtain now; our Library does not own a copy, so I am fortunate to have my own.

There are many books by Ure in our collections, but interestingly, none have anything to do with anatomy or the medical applications of electricity. By the 1830s, Ure’s interests had turned to manufactures, especially textile manufacturing, and he published a number of very popular works on these subjects. We surmise they were popular because they went through many editions. We might talk about these one day, or we might not. It is hard to surpass the experiments of Nov. 4, 1818, in Glasgow.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.