Scientist of the Day - Albert Curtz

Albert Curtz, a Bavarian Jesuit mathematician, died Dec. 19, 1671. We have four books by Curtz in our library, one of them exceedingly rare. Typically for Jesuit mathematicians, all four books have title-page engravings or frontispieces. We are going to discuss the rare treatise of 1653, and bring in a frontispiece from a later Curtz work, as well as a title-page engraving from an earlier Jesuit mathematical work by a different author. It is a day to celebrate title-page engravings, Jesuit love of allegory, and patronage in the age of the Habsburgs.

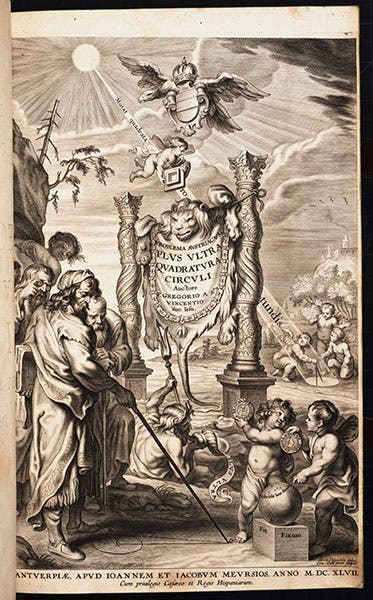

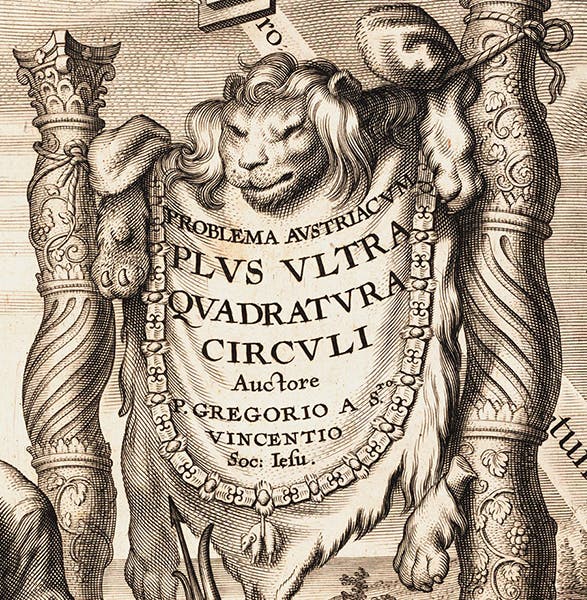

Curtz’s slim volume of 1653, Problema austriacum, The Austrian Problem, appears to be a continuation of a long-standing Jesuit interest in the problem of squaring the circle – finding a way, geometrically, to construct a square with the area of a given circle. We say that because Curtz’s title, Problema austriacum, was taken unchanged from one of the best-known Jesuit books on the problem, Problema austriacum plus ultra: quadratura circuli, by Grégoire de Saint-Vincent, 1647.We show here the engraved title page of that work (second image) , and a detail of the title panel from the engraving (third image), so that you can see the “Problema austriacum” part of the title. If you are interested in the circle-squaring emblematics at work here, see our post on Grégoire de Saint-Vincent, with lots of details of the imagery.

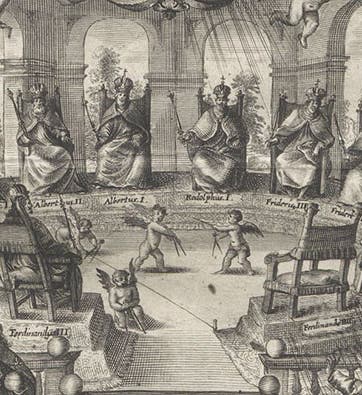

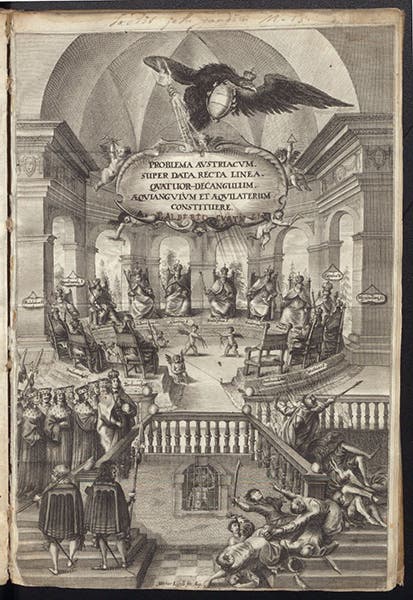

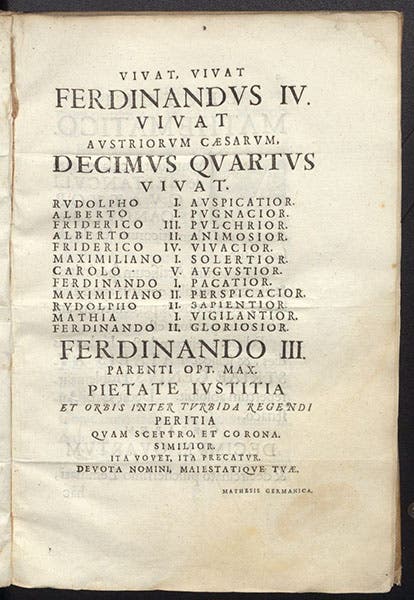

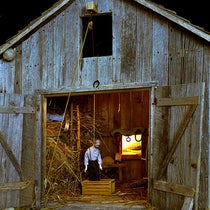

Curtz’s book, however, is about a different Austrian problem, one of his own devising. He was seeking the patronage of the Archduke Ferdinand, who was next in line to become Holy Roman Emperor. Ferdinand would then become the 14th Habsburg to lead the Empire, starting with Rudolf I. Curtz wondered, what if the 13 previous emperors wanted to welcome the 14th to their number – how might one arrange such a convocation? On one page of the treatise he listed all 13 previous emperors, with Archduke Ferdinand, soon to become Ferdinand IV, at the top (fifth image). Curtz then offered one solution on the frontispiece – 14 imperial thrones arranged in a circle (first and fourth images).

But it would certainly help to have a 14-sided table to sit around. This is Curtz’s Austrian problem, to construct a 14-sided polygon, using Euclidean geometry only. It is not quite the same as squaring the circle, but it is definitely related, inscribing a 14-sided polygon in a circle. The book goes through the solution, and at the end, we see the successful result – a 14-sided imperial table. This Austrian problem was solvable.

Unfortunately, Curtz’s elaborate play for patronage went for naught, as Archduke Ferdinand died of smallpox the next year, in 1654, and he never did become Ferdinand IV. Curtz was apparently not interested in figuring out how to construct a 13-sided table, so he returned to a project that he had been working on for some years, editing and publishing the works of Tycho Brahe, who had been the Imperial mathematician under Emperor Rudolf II. The work was finally published in 1666, under the pseudonym (and anagram) Lucius Barrettus. Curtz could not resist including a frontispiece (one of three frontispieces) showing the four Habsburg emperors who had hired Tycho and supported the publication of his complete works (seventh image). He did like his Habsburgs! The only new face is Leopold I at far right, the younger brother of the archduke, who became Emperor in 1657, after Ferdinand’s untimely death.

Curtz was 71 years old when he died in 1671. The other two books we have of his concern a mathematical instrument invented by Emperor Ferdinand III, and they both have allegorical engraved title pages as well. But we have had enough patronage-seeking for one day. Perhaps, in a future post, we will take up the matter of Ferdinand’s ruler.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the Hory of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.