Scientist of the Day - Adolphe Millot

Adolphe Philippe Millot, a French illustrator and lithographer, died Dec. 18, 1921, at age 64. Millot was one of hundreds of scientific illustrators who made valuable contributions to thousands of scientific publications in the 19th century, by providing high quality images in the form of woodcuts, engravings, and lithographs, but who have drawn almost no historical attention. In many cases, we do not even know their names. We have featured many scientific illustrators in this series, such as Elizabeth Gould, William Swainson, Walter Hood Fitch, Charles-Lucien Bonaparte, and most recently, Philip Reinagle, but most of these are well-known figures, either because they published under their names, or were writers in addition to being artistically gifted. But many illustrators, excellent ones, were often not even mentioned in the books they so enriched with their artwork; sometimes they were not even allowed to sign their plates with their names or initials. So we like to give them some long overdue attention whenever we can, even when we can do little but show their prints.

Millot is such an artist. We know he was the senior illustrator at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. But that's all we know. He presumably had a family, knew many French naturalists who are well know, and perhaps even had a certain social standing. There might well be papers and records in the archives of the Museum that would tell us more about him. But no one seems interested in unearthing such documents and adding a little flesh to the bare-bones knowledge we have of Millot and dozens of others.

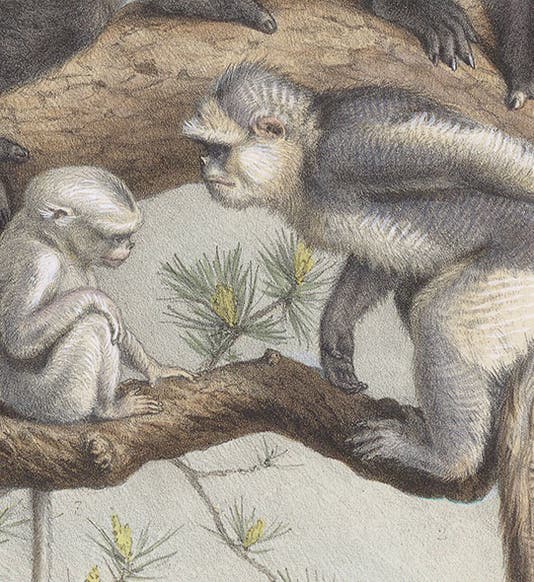

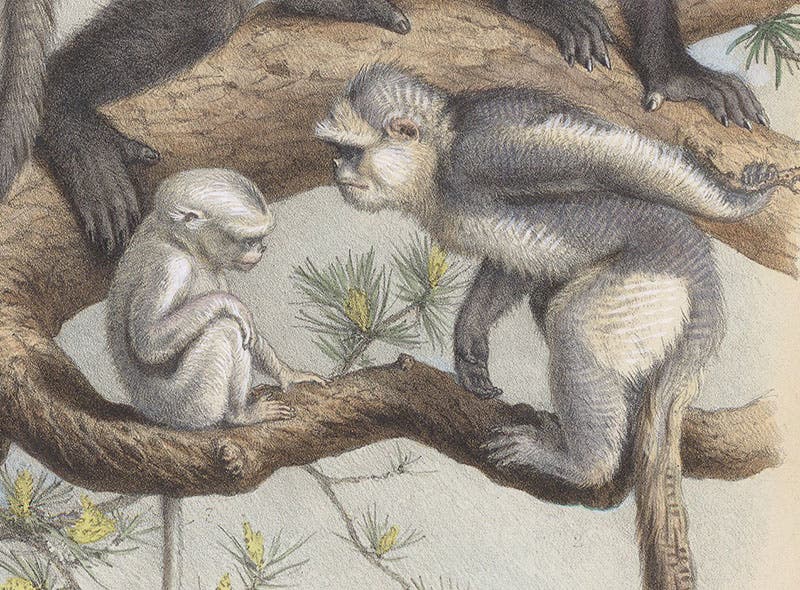

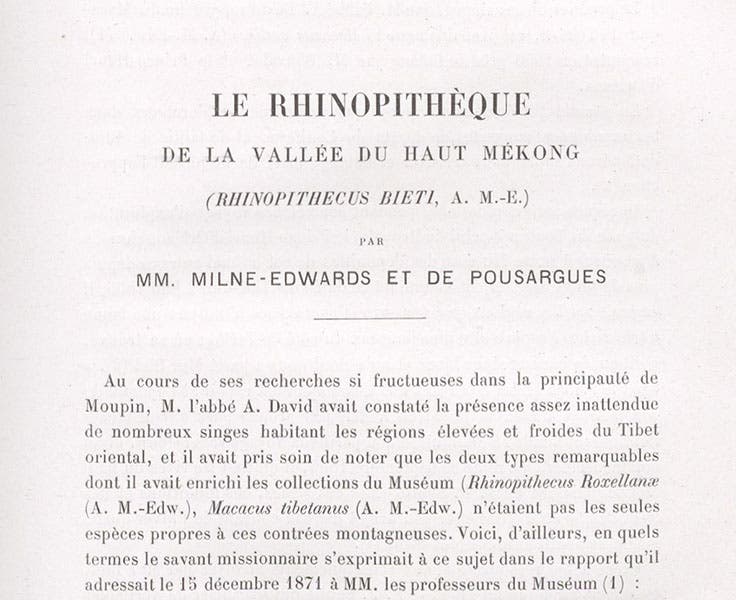

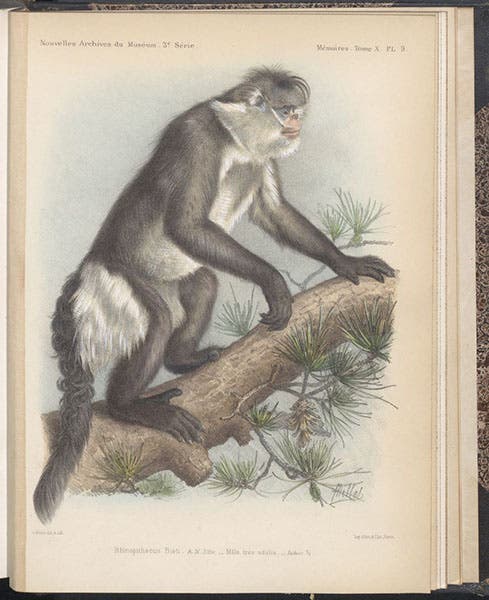

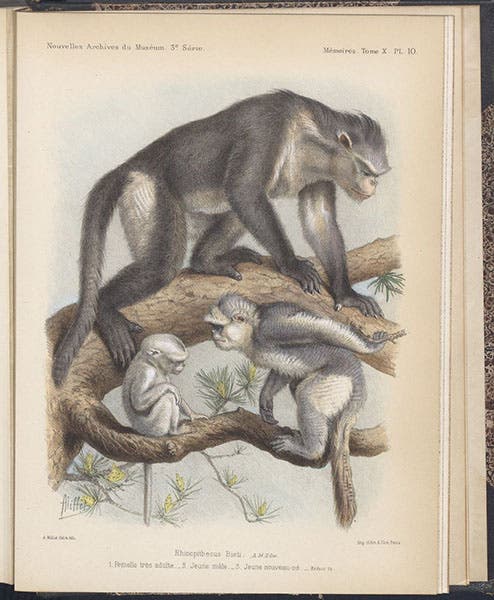

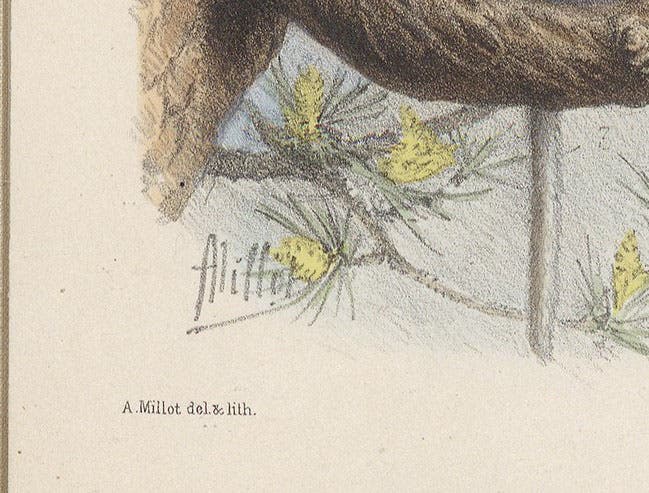

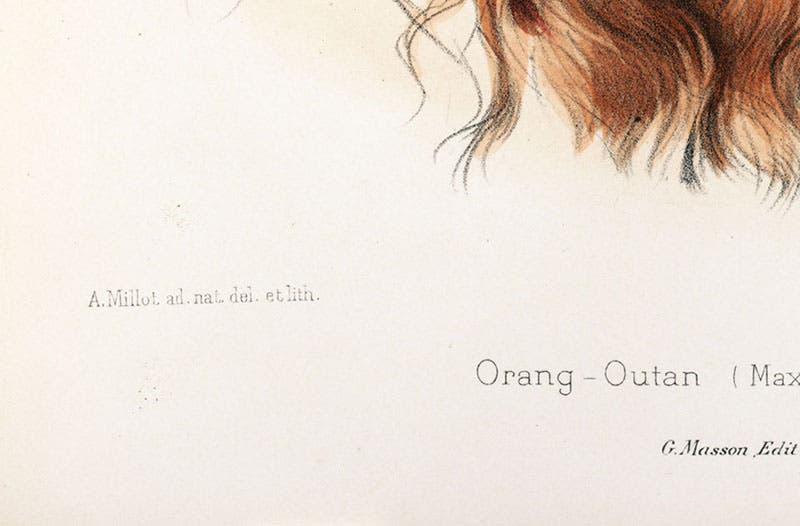

I could find no portrait of Millot, which is a problem right at the start. We want to know what these artists looked like. All I know about him is that he illustrated articles for the Archives and New Archives of the Paris Museum of Natural History for the decades of 1890 and 1900, and I know this only because I leafed through two dozen volumes, looking for plates with artists’ signatures, and finding his. Millot appears to have collaborated primarily with Alphonse Milne-Edwards, a prominent French naturalist. Because Milne-Edwards wrote mostly about primates, I know Millot as a primate illustrator. We show images here from two of his articles. In 1898, Milne-Edwards wrote a 20-page monograph about Rhinopithecus bieti, the black-and-white snub-nosed monkey, found in northern Vietnam, specimens of which were collected by Prince Henry of Orleans in the early 1890s and given to the Museum. To illustrate the article, he asked Millot to contribute four plates, two showing live animals, and two showing skulls. The plates of the animals in living poses are remarkable, considering that Millot was working from skins and had to construct the poses with his lithographic pencil. One plate shows a solitary male (third image), and the other depicts a female, with adolescent male and a newborn (fourth image). In a detail of the latter (first image), the young one is being scolded by his big brother. These plates are both chromolithographs; meaning they were printed in color. We see Millot’s signature in another detail (fifth image), and a printed credit line, indicating that Millot did both the drawing and the lithograph.

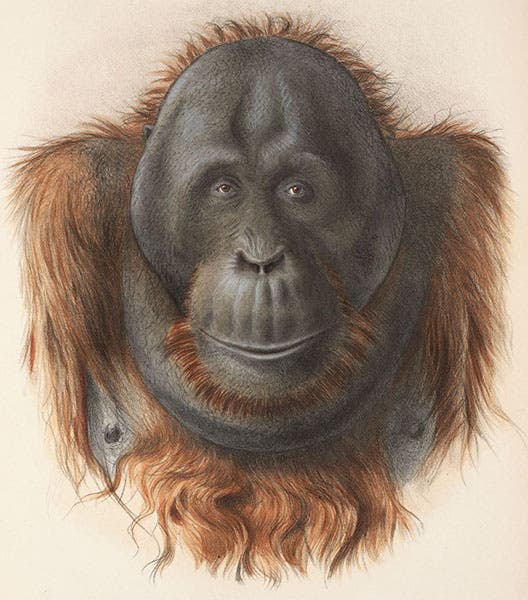

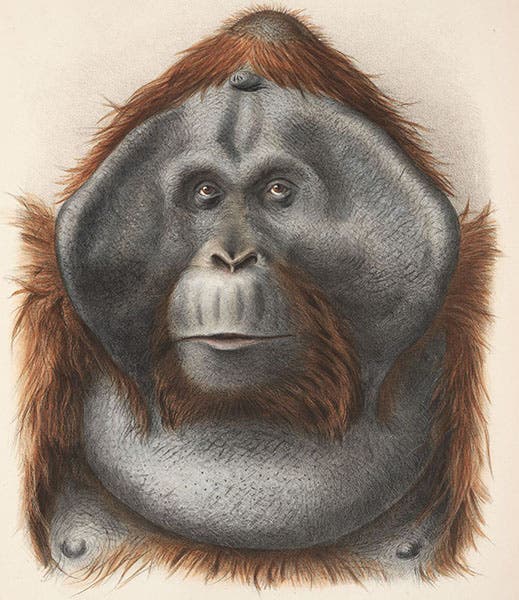

The other two lithographs by Millot that we show here accompanied another monograph by Milne-Edwards, this one on two orangutans, Max and Maurice, former denizens of the Paris Menagerie, who passed away in 1895 and were commemorated by Milne-Edwards. We saved them for last, even though chronologically they came first, because we included them once before, in a post on Milne-Edwards, and because they deserve to bat clean-up. They are in my opinion the most remarkable portraits of great apes ever drawn and printed, with the possible exception of the lithograph of a chimpanzee by Marie Firmin Bocourt, that appeared nearly forty years earlier in the very same journal, and which we featured in our Grandeur of Life exhibition in 2009. Note how much more vivid the orangutans are than the monkeys – that is the difference between hand-coloring (the orangs), and printed color (the monkeys)

Millot went on to do thousands of illustrations for the Larousse Encyclopedias that appeared in various forms in the early 20th century. I cannot show you any from our collections, because for some reason we do not have any Larousse encyclopedias, and in a way, I am glad, because that was journeyman work, far below the kind of creative commissions that Millot deserved, commissions such as bringing Max and Maurice back to life, and energizing the little snub-nosed monkey. There Millot was allowed to shine, and shine he certainly did.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.