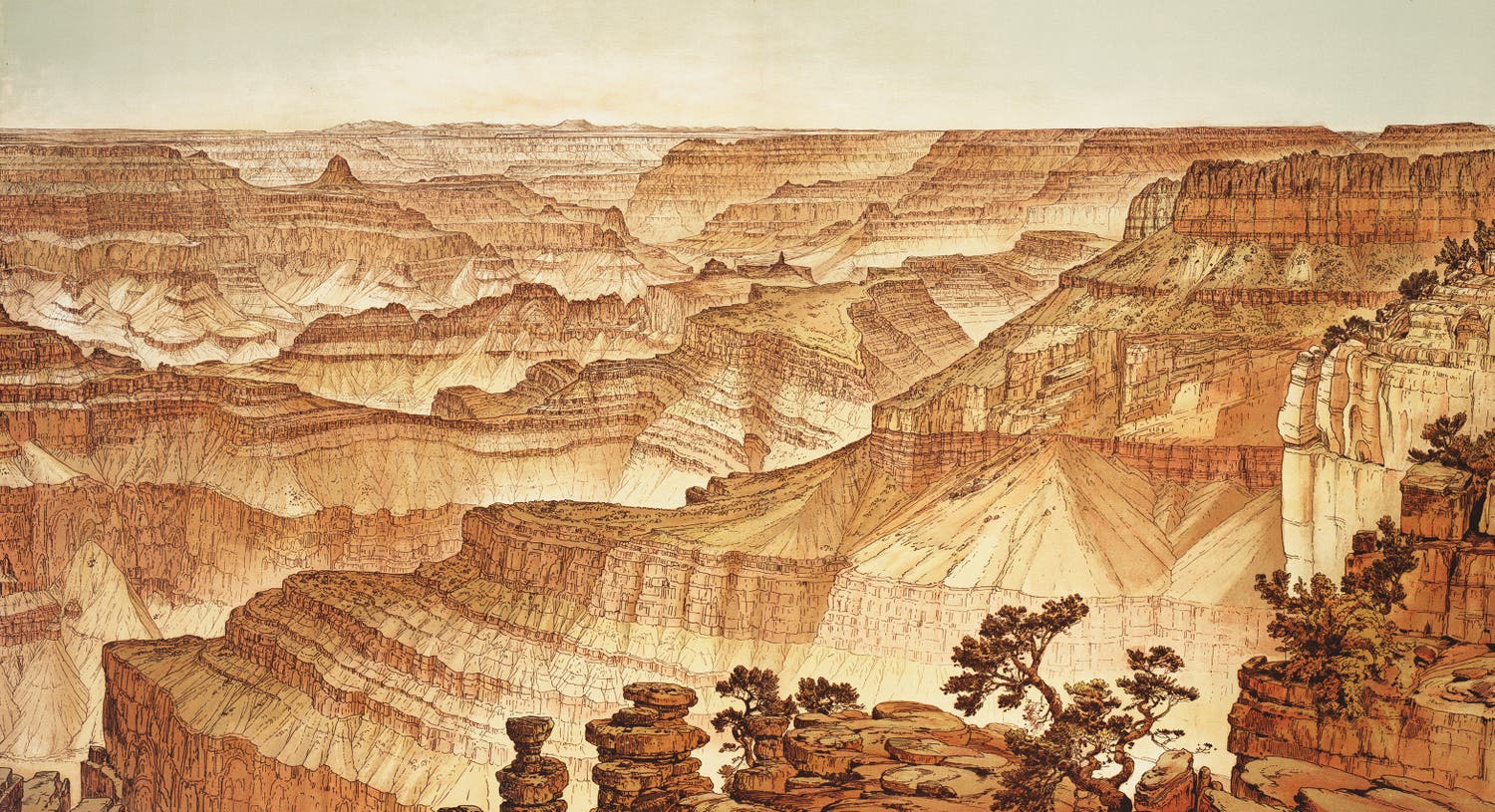

Perspectives on the Grand Canyon: Willian Henry Holmes

When geologist Clarence Dutton headed back to the Grand Canyon in 1880, under the auspices of the newly established U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), he had in his entourage two of the finest geological artists in the country. Thomas Moran had painted at Yellowstone, the Tetons, and the Green Mountains, and his Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone was hanging in the halls of Congress. William Henry Holmes was a talented draftsman, some nine years younger than Moran (and six than Dutton), and also a geologist, which Moran would never have claimed to be.

Holmes was just back from a year’s study in Munich when he was sent, in July of 1880, to join Dutton and Moran and the rest of their party on the border between Utah and Arizona, along the Colorado River. He arrived in short order (thanks to the rapidly expanding transcontinental railroad), and soon began to sketch views of the Grand Canyon (or Cañon, as they called it) from North Rim vantage points such as the Kaibab Plateau, the Toroweap (the only vantage point from which you can see the Colorado River at the bottom of the canyon), and a site that Holmes would soon make famous, Point Sublime. Moran painted as well, but the two men had very different ideas on how to paint the landscapes of the American West. Moran sought grandeur and spectacle, and he was not at all averse to moving the landscape around to achieve the effect he desired. He had no interest in being a cartographer or stratigrapher.

“View from Point Sublime, Looking South,” chromolithograph after drawing by William Henry Holmes, in Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, by Clarence Dutton, Atlas, pl. XVI, 1882.

Holmes, on the other hand, wanted his sketches to be of use to geologists. His drawings of strata were exact and accurate, which in the case of the Grand Canyon, required delineating thousands of strata as precisely as possible. And because he was an artist, he had a way of doing this in a manner unfamiliar to geologists, which is to say, stylishly. Holmes wanted his compositions to be as balanced and harmonious as possible, but he preferred to move his own viewpoint to improve the composition – he never resorted to moving landforms or even trees from one place to another.

| The result of the collaboration was the most beautiful book ever published by the USGS, the Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District (1882), consisting of a quarto text volume, written by Dutton and copiously illustrated with wood engravings derived from artwork by Holmes and Moran, and a folio Atlas of 22 large double-page lithographed plates, mostly based on drawings by Holmes. The views in the Text volume, being smaller and mostly uncolored, tend to show individual landforms such as “A Gable with Pinnacles,” depicting a structure on the Toroweap, and “Vishnu Temple,” a cap formation that, to Dutton (who named it) resembled a Hindu shrine. Both images were pen drawings by Holmes that were converted to wood engravings or photo-engravings for printing. |  “A Gable with Pinnacles – the Toroweap,” wood engraving after pen drawing by William Henry Holmes, in Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, by Clarence Dutton, Text vol., plate 16, p. 84, 1882. |

Most of the plates in the Atlas are tinted lithographs, meaning they were printed from several stones, each adding a different earthtone color. The most arresting section of the Atlas is undoubtedly a three-part sequence called Panorama from Point Sublime, where Holmes provided three views of the Grand Canyon, looking east, south, and west, from a single vantage point on the North Rim. The three lithographs form a continuous panorama, should you remove them from their binding and place them side by side. In the first of these, “Looking East” (see detail), Holmes contrived to put himself and Dutton into the picture, a clever way of indicating that the Atlas was very much a collaborative effort.

There is only one painting by Moran in the Atlas, “The Transept – Kaibab Division,” and most viewers really like it and prefer it to the less dramatic renderings of canyon walls by Holmes. It is indeed a lovely work of art; however, it is easy to see how a geologist like Dutton would find it useless in helping him understand the history of the Grand Canyon, for there is no reliable detail in it. Masterful though it might be, Moran’s “Transept” is still just an artist’s impression of an awesome vista, meant to stir the heart, but not the mind. Holmes sought to educate and inform first, but he still managed to bring out the awe in all of us.

“The Transept, Kaibab Division, Grand Cañon,” chromolithograph after painting by Thomas Moran, in Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, by Clarence Dutton, Atlas, pl. XVIII, 1882.